Nowadays, there is a standardized formula for countless Christmas movies. Recurring themes range from stories of redemption to emphasizing the warmth of a strong family bond and festive cheer. Yet, it is always fascinating to see flicks that depart from the usual holiday tropes and instead focus on an issue that may be too challenging for casual moviegoers, who prefer a more sanitized portrayal of reality for the holidays. Shutaro Oku's unusual yet effective feature, “Death of Domomata,” uses the happiest time of the year to explore recovering from drug addiction and the harsh realities that come with a dysfunctional rehabilitative environment.

As a filmmaker, Shutaro Oku is still relatively unknown to many but has made a decent amount of films, a notable one being “Seiza.” Generally, he's more active in theater, having directed various theatrical presentations, including a stage play version of “Ghost in the Shell.” Oku is still heavily involved in the profession today and often incorporates aspects of theater into his movies, including “Death of Domomata.” Along with those theatrical elements are frequent emphasis on surrealism and documentary style filmmaking to add a grounded yet twisted rendition of reality.

In a rundown rehabilitation center, the audience follows six young women: Tobe (Domomata), Tomoko, Hamada, Sawamoto, Seko, and Aoshima. All have been admitted for drug addiction, which has further perpetuated their mental struggles. Their situations are only made harder by the center's poor management, filled with abuse and neglect. The girls only have each other to rely on, occasionally finding comfort through activities such as painting and theater performances. However, on the morning of the center's patient-led Christmas Eve recital, the lead dies, with the fault being directed at the administrators.

Check also this interview

“Death of Domomata” is not for the faint of heart, as its subject matter can be potentially triggering and often displayed in graphic detail. It's important to note that this isn't necessarily a plot-driven film but functions more as a visceral psychological experience, putting viewers into the shoes of the movie's troubled protagonists. Beyond the country's controversial drug policies, empathy for people struggling with drug addiction is greatly undermined in Japan, from a lack of general awareness to limited support resources available, all of which are addressed here. These severities are only worsened when put in a destructive environment like the one the six women live within. Additionally, how the film utilizes Christmas, including the rehabilitation center's yearly festive recital, is focal to what it communicates. This holiday is a time of happiness with loved ones and a celebration of existence. Yet, perhaps many people take this for granted while many are struggling in continuous despair

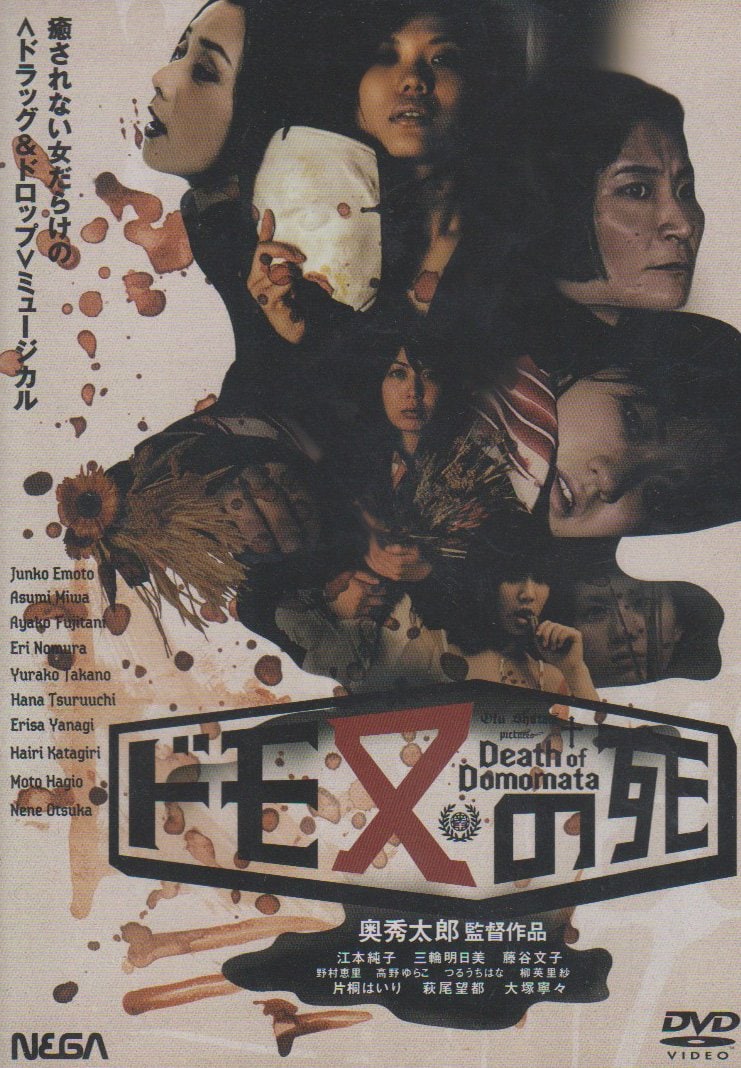

The audience gets to know the six women and who they are, which helps humanize them and allows viewers to empathize with them as they deal with their struggles. It's all heightened by excellent performances from Junko Emoto, Asumi Miwa, Ayako Fujitani, Eri Nomura, Yurako Takano, and Hana Tsuruuchi. The supporting players are also very good; standouts include Elisa Yanagi and Hairi Katagiri.

“Death of Domomata” is shot like a documentary, adding an intentionally uncomfortable feeling to the experience. The low-budget aesthetics captured through Shu Kageyama and Masayuki Yonaha's camerawork invoke a sense that viewers are trapped in a nightmare while witnessing what feels like to live the real dysfunctional lives of troubled patients in a chaotic rehab center. Hana Tsuruuchi's music score adds to the insanity, sometimes being uplifting, which creates a sad contrast when combined with the movie's often disturbing imagery.

“Death of Domomata” is a polarizing film, and its sensitive and harrowing subject matter may be too much for some viewers, but it's worth watching. It's well-acted and raises awareness of Japan's lack of coherent support for people who struggle with drug addiction and live with mental turmoil. How it incorporates Christmas into its storytelling helps drive home the point that the so-called happiest time of the year slogan becomes perhaps questionable when countless people still suffer, whether from their inner struggles or the environment they are forced to inhabit.