Hayao Miyazaki's first feature in 10 years crept into theaters with a bang. After many years of a wish-washy retirement, the 83-year old director of beloved Studio Ghibli titles like “Spirited Away” and “Princess Mononoke” returned with his beautifully animated “The Boy and the Heron.” Notably, though the film appeared in Japanese theaters sans PR (a deliberate choice on Miyazaki's end), the movie has taken the world by storm. I personally have been hearing about it since the day of its premiere: first, friends reporting back on their summer Japan travels; then other journalists at TIFF; and finally, within vicinity, from neighbors and colleagues near me, as the film scoops the coveted No. 1 spot in the North American box office. With GKIDS' North American release hitting the high of the holidays (and in due turn, the beginning of awards season), it is almost no wonder that film critics have been tittering about “The Boy and the Heron's” potential Oscar campaign for Best Animated Feature.

Check also this article

But perhaps the distraction of gossip is precisely what Miyazaki resisted against with the film's noticeably unannounced release. “The Boy and the Heron” is not exuberantly flashy by any means. The film – an adaptation of Genzaburo Yoshino's 1937 novel, “How do you live?” and a semiautobiographical reflection of Miyazaki's own schoolboy days – starts with tragedy. Here, in 1930s Japan, the young Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki) loses his mother in a fire in Tokyo. Shortly after, he, his father (Takuya Kimura), and his new step-mother Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) then move to the countryside, where they reside in the Gray Heron Mansion.

On paper, their new lives seem idyllic. The elderly grandmothers attending to the manor fuss over Mahito; Natsuko's face is a-glow with her pregnancy; Mahito's father showers his young family with material comforts and affection. Mahito, however, cannot seem to accept his circumstances – certainly not his stepmother, let alone his new school – when he realizes that strange things are afoot in the mansion. The (titular) heron calls for Mahito through his bedroom window. An army of frogs climb up Mahito's torso. A school of fish sing in chorus from the river. And – to top it all off – Mahito stumbles upon a mysterious staircase, seemingly blocked off before, within the crevices of a sewer. When Mahito turns for help, he finds that Natsuko too disappears. And of course, in an “Alice in Wonderland”-like fashion, he must follow the heron through the sewer hole to save her, before she is gone forever.

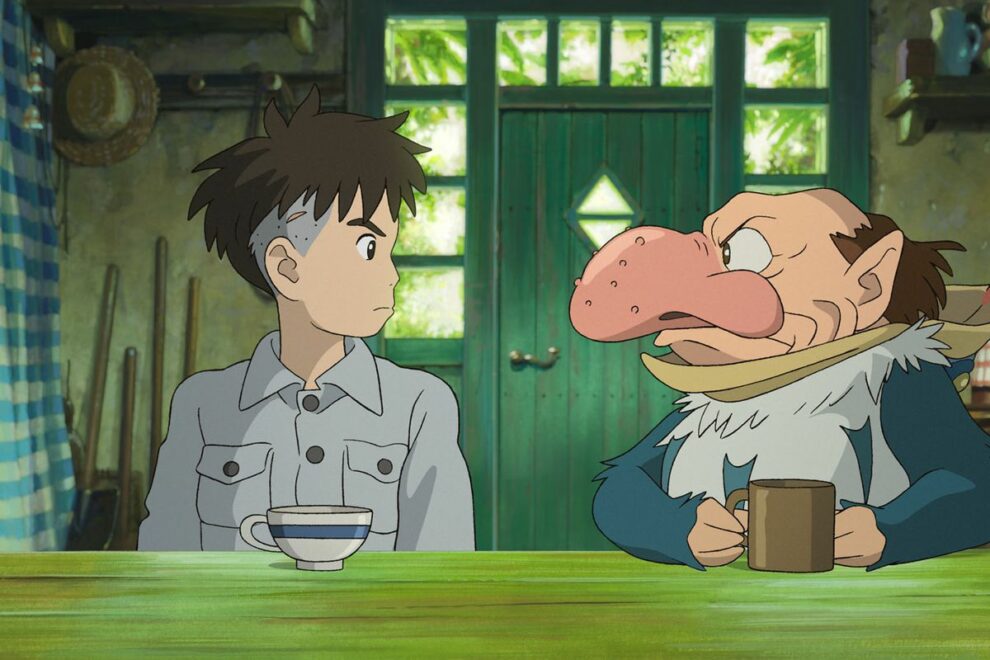

Though the beginning of the “The Boy and the Heron” adopts more somber, historical tones like “The Wind Rises” (2013), Miyazaki lets loose his creative juices the deeper we travel into the sewer-hole. But instead of simply spinning entirely new fantasies, he uses the universe of “The Boy and the Heron” to reflect upon the entirety of his oeuvre. Lovers of Ghibli are sure to marvel here. When a warty little man emerges from the heron's mouth, it's hard not to think of Yubaba, the equally-verrucose (and avian-inclined) antagonist from “Spirited Away” (2001). The black dustball-like Susuwatari from “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988) seem to reincarnate into the crowd of white, cloud-like, happy-go-lucky Warawara. The fierce spirit of Princess Mononoke (1997) seems to live on in the fire-wielding, time-bending Lady Himi (AIMYON). Glimmers of the ravenous waves in “Ponyo” (2008) and the celestial “Castle in the Sky” (1986) shine through even, as the universe within the sewer-hole begins to deconstruct. It is almost as if Miyazaki is telling us that, despite all these years, he still wields the same innocent wonder as when he was a boy.

This impassioned indulgence comes through in other references to the Disney of Miyazaki's childhood. It is difficult to not compare the absurdity of Miyazaki's multicolored parakeet army to that of the cards in “Alice in Wonderland” (1951) or to directly compare some shots – such as the parakeets' shadows creeping up along the walls – to Mickey's dancing broomsticks in “Fantasia” (1950). But I don't mean to belabor this review with references. In the end, that's not really what “The Boy and The Heron” is all about. It's not so much about looking to the past as it is re-living the present – whether that it is through the acceptance of the film's dreamlike logic of unfinished plotlines and open doors – and wandering our way towards the future, together.

And this doesn't even account for the stellar detail Miyazaki pays to the animation. He addresses Mahito's memories of his mother with a flame-like wispiness, giving way to more experimental animation. He otherwise delivers the Ghibli brand to the T: each extra frame captures the gentle rise and fall of Mahito's breathing chest, the slow gravity of the heron spreading his wings, the seriousness of each deliberate step. Over the course of three years, it is almost as if the precise detail of the exact moment is more important than the linearity of the overall storyline – giving the film an exquisite, dreamlike softness.

All in all then, “The Boy and the Heron” can be read as largely self-indulgent. With painstaking detail dedicated to each frame and a soaring score (as always) from the ever-reliable Joe Hisaishi, “The Boy and the Heron” is an aesthetically pleasurable film to watch. In a way, it feels as if this film also marks Miyazaki's final send-off. As the octogenarian director reminisces over what he has lived through and what he has done, it seems – with Mahito's final emergence from the sewer-hole – that Miyazaki is clearing room for the animation world anew. If this does end up being his last film – and touch wood if so! – then “The Boy and the Heron” marks a masterful capstone to his career.

“The Boy and the Heron” can be seen in North American theaters now. North American distribution is managed by GKIDS.