by Sophia Ng

“You sound like one of those guys,” he spits, “Men who get girls pregnant then say ‘Oh, I understand', and sign the form like it's none of their business.” Aki says nothing to that, silently taking a gulp of water. “But I'm the one who bears the risk whether it's childbirth or an abortion.”

In a literal reversal of roles, the 2022 comedy-drama “He's Expecting (Hiyama Kentaro ō Ninshin)”, directed by Yuko Hakota and Takeo Kikuchi, sees Hiyama Kentaro, a 33 year old cisgender man having an emotional outburst, lashing out at his female partner's apparent failure to empathize with his predicament—being pregnant and the eventual trauma his body would be put through regardless of whether or not they keep the child. Currently on Netflix, this limited series based loosely on Eri Sakai's manga 2012 series, “Hiyama Kentaro no Ninshin”, explores the concept of cisgender male pregnancies within the conservative contemporary Japanese society where the phenomenon is rare, but not an impossibility.

Internationally acclaimed actor-director Takumi Saitoh stars in the titular role as the successful 33 year-old advertising executive Kentaro Hiyama, the rising ace of his company, with his female partner Aki, played by the lovely Juri Ueno, best known for her lead role in the live action adaptation of “Nodame Cantabile”. A blossoming career coupled with a calendar chock full of a different girl's name each day, Saitoh's character is living his best bachelor life. Until he learns he's pregnant.

Check also this interview

At first the solution is simple—get an abortion. He never meant to get into a serious relationship anyway, let alone have children. But when he changes his mind and keeps the child, we get swept along in his journey re-navigating life as a pregnant man. The series does a great job balancing the comedic elements of a man's struggles to keep up with his rapid bodily changes while working in a male dominated company, with more complex themes of gender roles, and discrimination.

The series' premise alone is intriguing enough to warrant a watch—what would it look like if men could bear all the pains and inconveniences of pregnancy in the place of women? In the earlier episodes, we see Kentaro's body start to change, he starts producing breast milk that leaks through his shirt while he's at work, his facial hair grows back at an alarming rate which gives him a dishevelled appearance no matter how he tries to stay well-groomed. Initially unable to be honest with his boss and colleagues about his pregnancy, Kentaro chalks up his odd behaviour to feeling unwell, inadvertently undermining his own professional capacity in the eyes of his boss. As his perfect bachelor life starts to fall apart from the moment he finds out about his pregnancy, the “unique” predicament of Saitoh's character only serves to highlight the lived realities of countless women everywhere that go largely unacknowledged.

“I realized something. Interrupting my career to have a kid doesn't necessarily mean lowering my sights. I'm actually developing as a person, so one day this experience will surely be reflected in my work,” Kentaro monologues to his female colleagues in the last episode as he goes on parental leave. The women stifle their laughs at his sudden spark of enlightenment before the older one humbles him with a reminder that it's “always been that way for us”.

What's interesting about the premise of the show is that while males can get pregnant, the roles aren't completely reversed; the females still make up the majority of the child bearing population. This then turns the pregnant males into a marginalized group that gets discriminated against, with others calling them “gross”, “unmanly”, or taunting them with shouts of “mother”. With the possibility for males to carry a child instead, conventional gender roles are subverted, and the responsibility or burden of child-bearing no longer lies solely with the woman anymore; either party can fulfil that role. On one hand, it's “a miracle”, as Aki expresses—she can have a child of her own without having to go through the gruelling nine months herself. And on the other hand, where does that leave Aki as a mother? As she discusses their future, she admits that she can't play the role of a “regular mother” since she isn't the pregnant one and won't be giving birth, but what does it really mean to be a regular mother?

During a gathering, Aki and her friends get to discussing male pregnancies and one of them remarks that it's sad for the partner of a pregnant male as she “can't fulfil her role as a woman”. If females don't have to bear the child and nurse the child, are they not fulfilling their roles as women? What then does it mean to be a woman? And is it tied to our ability to bear children? The whole series does a great job challenging and exploring the stereotypical gender roles, posing big philosophical questions of what it means to be a mother, a father, a man, and a woman. Is the title of mother intrinsically tied to the individual's ability to carry and birth the child? And if so, what would it mean to be a pregnant man? Would that make him a mother instead of a father? In mainstream society, the stereotypical gender roles dictate that the man works to provide for the family and the woman bears the children and cares for them. Yet, when the roles are reversed, the woman is perceived as not fulfilling her role even though a child of hers is being produced just the same, with her male partner doing the childbearing.

The juxtaposition of pregnant males against pregnant females in this reimagined version of Japan only serves to highlight the existing struggles of females and the inherent societal roles imposed upon them due to their biological construct. It's as America Ferrera's character says in “Barbie”, “It is literally impossible to be a woman”. Women are expected to carry the child and bear all the trauma inflicted on their bodies from the process, then to stay home and take care of the child and housework, while their partners are bestowed the title of breadwinner for working to provide. Yet if males are able to bear the child instead, the roles aren't equally reversed, the women aren't heralded as breadwinners but labelled as not fulfilling their jobs as women. Even when we win, we lose.

The series ends on a hopeful note however, with Kentaro on parental leave at home with his baby as they video call Aki from her new job overseas, the very picture of a happy family. Though most of the problems that arise do get resolved fairly quickly—which removes any impression that there is really anything at stake—it works for the length and pacing of this limited series. Saitoh made for an amusing lead fumbling with the confusion that comes with being a pregnant male and demonstrates good chemistry with Ueno as his onscreen partner, but the series probably would have worked well too if other actors were cast in their place. However, Saitoh's tall build and rugged appearance definitely adds to the comedy when juxtaposed against his character's more vulnerable moments as he struggles and sometimes fails to tackle each new challenge pregnancy throws at him.

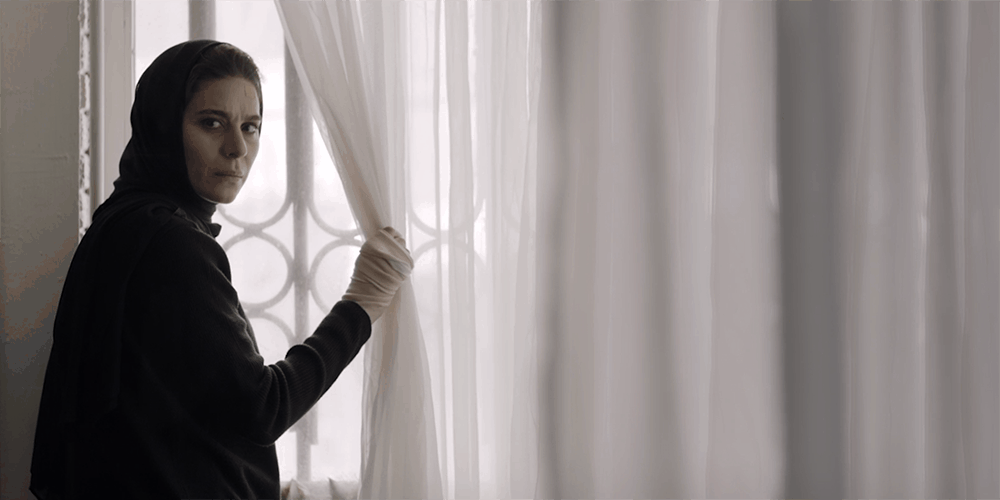

The series isn't visually striking and features mostly urban locations and cityscapes. Yet, even with the largely dull and sombre colour palette maintained (be it the surroundings or even the characters' clothes), and the gravity of the topics addressed, the show manages to keep viewers engaged without it getting too heavy or monotonous. The cinematography expertly creates a sense of introspection with the night scenes, contrasting the soft warm glow illuminating the characters with the lightly tinted blue or green backdrops, isolating them from the cool toned surroundings and creating the illusion of them being in their personal bubble. We are drawn into the characters' inner worlds for a moment, as they contemplate their worries for the future and ruminate on the bigger questions of life. Coupled with pockets of mild comedy sprinkled throughout the episodes, “He's Expecting” poses many relevant questions regarding familial ties and gender roles in the 21st century in a palatable way, as viewers are naturally drawn in to ponder the same issues plaguing the characters.

While the comedic elements are not likely to elicit a very visceral reaction from viewers, levity is often injected in the form of light and playful soundtracks, and instances where Saitoh's character unwittingly makes a fool of himself, giving the show the lighthearted balance it needs. With its quirky premise, its high production value, the way it explores familial relationships and presents an alternative to old fashioned perceptions of gender roles and relationships, “He's Expecting” is definitely worth a watch. Watching a cisgender man whine while going through the many pains countless women have had to endure throughout time will undoubtedly make for an entertaining time.