In my first review for the slapstick chronicles of silly villager Ah Niu (Ye Feng) and his Big Uncle (Wang Sha), we unpack the terror of living in a city ravaged by progress, alongside the guilt of desiring to partake in its consumerist pleasures. We learn an unspoken ‘truth' that for Ah Niu, the childlike icon of innocence, to remain a good person, he must remain poor. Lo and behold, the third of “The Crazy Bumpkins” series: “Big Times for the Crazy Bumpkins” (1976), sees a bag of money and jewels accidentally falling into Ah Niu's lap, making him actually rich. After 2 iterations of largely repeated gags, John Lo Mar's moral reflections on life in the new city enters a new curve, coming to a head in “Crazy Bumpkins in Singapore” (1976). Though this narrative shift is likely practical, it also ironically reveals the films' contradiction, as a marketed Shaw Brothers' product criticizing consumerist culture. By pushing Ah Niu and Big Uncle into proper coexistence with the transformed Hong Kong and Singapore, alongside bourgeois agendas at hand, “The Crazy Bumpkins” final chapters attempt to dissuade guilt towards partaking in consumerism.

In “Big Times for the Crazy Bumpkins”, the hard-hearted city finally rewards Ah Niu with a bag of loot. Ever the opportunist, his wiry Big Uncle immediately assumes control of Ah Niu's financial affairs for dubious schemes. Awkwardly barging into restaurants and villas for the first time, they step into the playground of the likes of senators and moguls, roping them in as supporting characters, rather than minor victims of their scams. As Big Uncle gradually robs and abandons Ah Niu, the lesson continues that consumerism causes the disease of greed and moral decay. Yet as with the movies before, Ah Niu escapes this disease by remaining his innocent, naive self. Despite constant material and sexual temptations, Ah Niu's nonconformity continues to shield him from what Yeo Min Hui, curator of the “Comic Relief” restrospective and exhibition describes as a “dominant culture” of consumerism and greed. From failing to conform to the gritty working class, Ah Niu continues to fail at understanding the nuances in the behaviors and codes of the rich. The exact opposite of his crook uncle, who makes a manipulative living by adapting and pretending to be other people. Lo Mar opens up the possibility that, like Ah Niu, you can enjoy luxury without conforming and compromising yourself. In other words, it is possible to partake in consumerism, but stay a good person. But how do you achieve this?

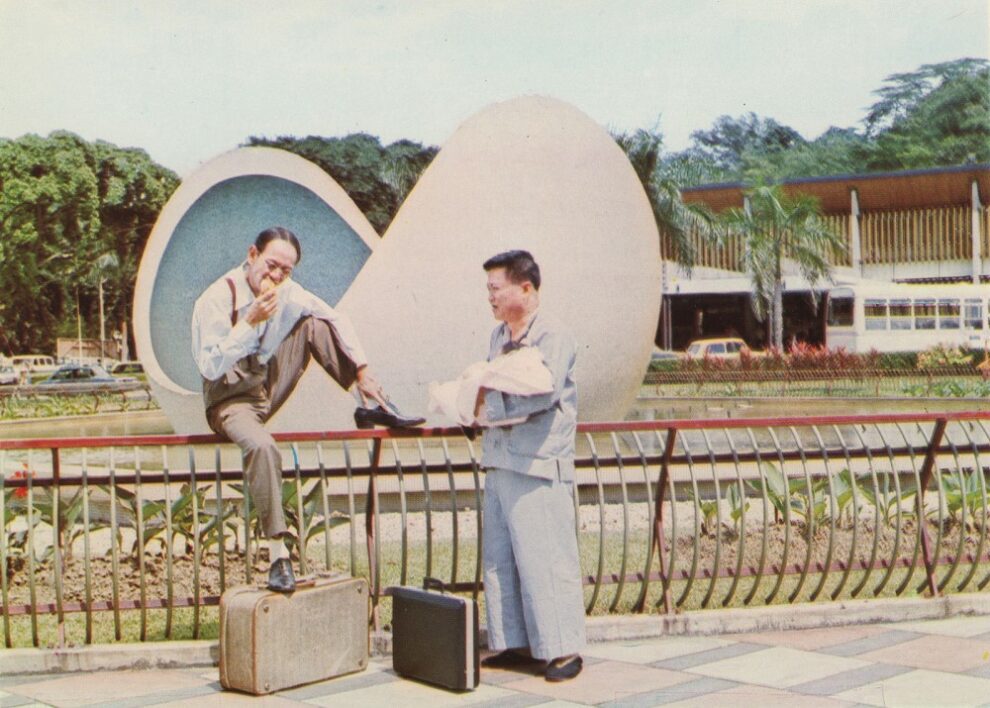

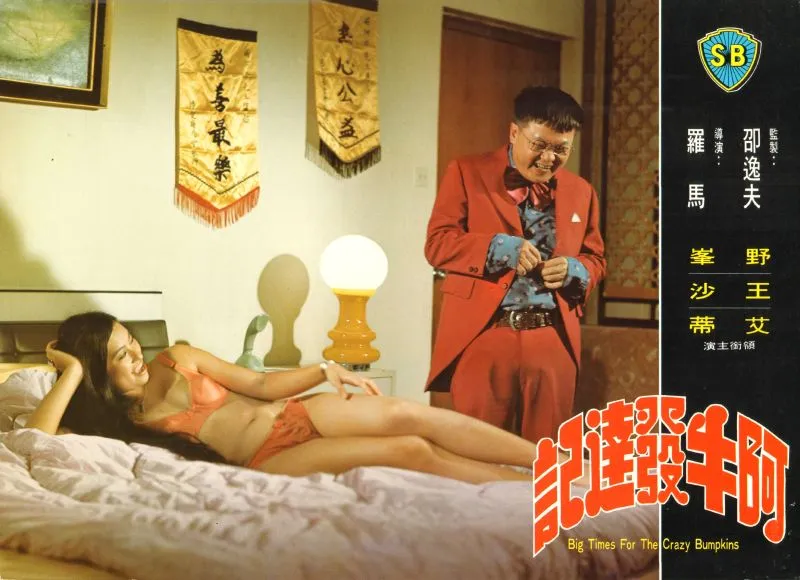

Lobby Card for “Big Times for the Crazy Bumpkins” (1976).

The next and final chapter, “Crazy Bumpkins in Singapore” answers this question with the utopically depicted garden city, where it is indeed possible to be rich but nice, because solid education has vanquished all bad moral influences. Mirroring “The Crazy Bumpkins” (1974), Ah Niu and Big Uncle move to the transformed garden city to reinvent themselves, running petty scams while hiding out from hitmen. Unlike the cutthroat and gritty Hong Kong, consumerist Singaporeans are forgiving and optimistic, such as schoolgirl An Ni and her upper-class parents. Their arcs lead us to blatant monologues in praise of education that are hard to ignore, including a schoolteacher's lecture on being righteous and self-sufficient. Jarring as they come, these scenes intentionally laud the very ‘concept' of Singapore, a hypothesis supported by the fact that studio head Runme Shaw was the chairman of Singapore's Tourism Promotion Board. Considering that the agenda behind this production might have been in part to market Singapore as a tourist destination, and to encourage spending and consumption, it is expected that the discourse will end up in favor of consumerism, instead of remaining poor, modest and humble.

Movies are after all, a product with which we seek pleasure. Though I previously approached the series with optimism in its efforts to soothe our moral anxieties, it is also undeniable that this soothing continually permits us to feed into the consumerist culture we criticize. One might also argue, citing Hans Magnus Enzensberger, that if consumerism consequently reflects very real human desires, it does little to renounce its temptations. While John Lo Mar's comedy softly critiques consumerist values, the bumpkins never sneer, and in fact highly relish any chance for a good meal, nice suit or hunk of cash. As the audience, we also desire nice things for the characters we love. It is this tension between desire for material pleasure and guilt over its perceived moral cost that runs the hamster wheel. This perceived moral cost vilifies consumerism as gluttonous. Hence initially, the riches enjoyed by the bumpkins must never be too much. Cash is always short-lived, and the poverty cycle plays a crucial part in Lo Mar's running gags.

While this tension proves intriguing, it's a bummer to sit through. If wealth is saddled with the threat of losing yourself and your good virtues, then the bumpkins must never succeed in becoming rich. After 2 features of the same goons trying and always failing, it gets depressing. Ah Niu's windfall might very well be a practical move to refresh the series and keep us around. Regrettably, this discomfort we have for poverty onscreen hearkens back to commercial cinema's allegiance with consumerist ideologies.

Representations of poverty, meant to evoke displeasure, are often heavily saddled with uncomfortable feelings of shame. Not just for those who are ashamed of being poor, but also those who feel guilt over their privilege. As such, movies addressing poverty, such as “Slumdog Millionaire”, largely accept it as an undesirable state, only introduced in order to be ‘fixed', to make way for the happy ending. Of course there is a multitude of social-realist cinema where characters never manage to escape poverty, with purposefully tragic, pessimistic endings that critique the idealist happily (or wealthily) ever after. However, the displeasure of “Factory Boss”' or “I, Daniel Blake”'s endings are also usually quickly resolved by the incoming credits roll. The audience would surely not sit around for another hour watching the story of their doomed lives. As a brainchild of desire and escapism, we find that commercial cinema, while perversely eager to depict the disenfranchised, is thoroughly disinterested in suffering that cannot be consumed. The trouble for “The Crazy Bumpkins” is that it is a series. There are sequels to be made, and consequently, the show must go on. In this construct, the point of Ah Niu's initial archetype as a crazy bumpkin, forever naive and struggling to make ends meet, eventually loses all appeal.

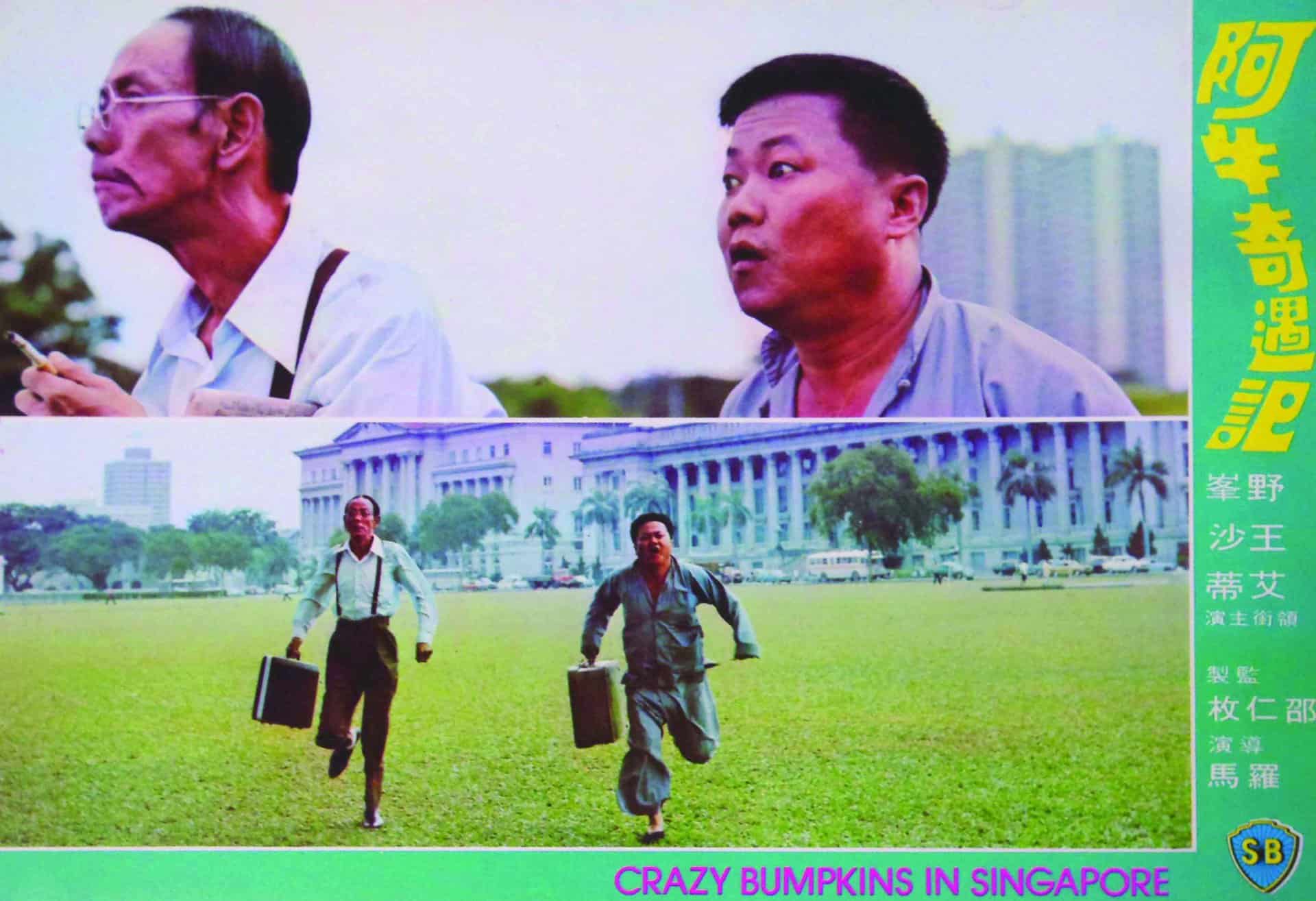

Lobby card for “Crazy Bumpkins in Singapore” (1976).

In an accompanying talk preceding the screening of “Crazy Bumpkins in Singapore”, which took place last weekend at Oldham Theatre for the “Comic Relief” restrospective, researcher Toh Hun Ping remarks that the film has been lauded by some as patriotic, for how it so keenly captured the city's modernizing landscape and “what the government was really trying to do”. For us, the language and education reforms of the 1970s introduced much of what we now characterize as ‘Singaporean': HDBs, English education, meritocracy. Invariably with every change, something has been lost to time. The most risible monologue in the film takes place after An Ni gives away her father's birthday present to Ah Niu, who is in need of cash for a sick infant. Tearing with pride, An Ni's father quite literally states that it is her education which has made her so morally upright, and he is glad for her to have the education he never had. After years of tackling the city's rapid progress, this scene seems to envision hope for future generations who live in a society that has normalised consumerism.

Looking back, Lo Mar, Ah Niu, Big Uncle and An Ni's father now belong to the era of Hong Kong's and Singapore's transitional phases. Though they may have doubted and struggled in the 70s, it seems they can now rest easy, believing their children will enjoy material luxury without the threat of moral decay. As a Singaporean myself, it is hard to unpack the sentiments I have for this strangely exploitative yet sincere film, that contradictorily celebrates the development of a Singapore that is by now, also obsolete. Our vantage point through the retrospective unpacks its many functions: as entertainment, social commentary, bourgeois product, collective memory, cultural document… There is no one way to view it.

Comic Relief: Film Retrospective and Exhibition on Wang Sha and Ye Feng runs until 7 April 2024 at the Oldham Theatre in Singapore. “Big Times for the Crazy Bumpkins” (1976) and “Crazy Bumpkins in Singapore” (1976) will each have a repeat screening on 7 April.