by Vedant Srinivas

Hou Hsiao-hsien's often overlooked masterpiece “The Puppetmaster”, part of a trilogy on 20th century Taiwan (the other two being “The City of Sadness” and “Good Men, Good Women”) recounts and dramatizes the turbulent life of Taiwan's most celebrated puppeteer, Li Tian-lu.

The film's introductory intertitles help establish the film's historical context: the 1995 Sino-Japanese War and the ceding of Taiwan to the Japanese, thus paving the way for fifty years of Japanese rule on the island until the end of the Second World War. Leisurely moving from Tian-lu's childhood to his adult life, the film provides us with vignettes that encapsulate the most poignant moments of his journey: Li's loving relationship with his grandparents, his adolescence in an abusive household, his apprenticeship with a marionette troupe, the gradual death of his loved ones, Li's marriage into a puppet theatre troupe family and his subsequent affair with a prostitute, and finally his involvement in propaganda work for the Japanese army during the Second World War. As Li Tian-lu's journey progresses, it also becomes an allegory for the history of modern Taiwan, and an investigation into its social and cultural mores, each phase of his journey in a sense mirroring important national landmarks.

And yet, despite its obvious use of a historical backdrop, “The Puppetmaster” is far from being a conventional historical documentary. Instead, as the narrative progresses, what comes to the fore is Hou's formally intriguing use of ellipses, narrative jumps, and offscreen space in the film, lending a certain impressionistic feel to its unfolding. Take for instance the scene revolving around Li's mother's death – the event is narrated to us in a lengthy voiceover, while the image stays focused on a long shot of a dusky village landscape, bordered by overarching trees and the outlines of huts. What in any other case would have been milked dry for its melodramatic potential is here treated almost as an aside, and the poignancy here emerges from it being juxtaposed with the relentless forward march of time. “The Puppetmaster” is replete with such Ozu-esque moments, where only the before and after of a narratively important event is shown: a pertinent example would be the aforementioned mother scene, or a later sequence showing the demise of Li's grandfather (who is only heard stumbling down the stairs in the darkness). A similar sense of elision can be experienced even in how the narrative jumps across events and timelines without providing any overt information (the arrival of Li's new step-mother is conveyed through a scene that shows the children's old sashes being replaced with new ones).

Oftentimes, Hou completely dispenses with conventional cause-and-effect narration, obliquely putting together what seem like two totally disparate episodes. Thus, towards the latter part of the film, we see Li bidding farewell to a Japanese friend, followed by an outdoor shot of Li's family on the move, only to find them living in what looks like the countryside, in the cluttered and dust-laden interiors of a coffin shop. This is followed by an interlude of scenes, in which we see the family getting used to their new surroundings, and also Li's father contracting malaria, which will eventually lead to his demise. It is only much later that we are provided a reason for this abrupt change in the story, namely that the family has been evacuated to a remote village because of enemy raids on Taipei.

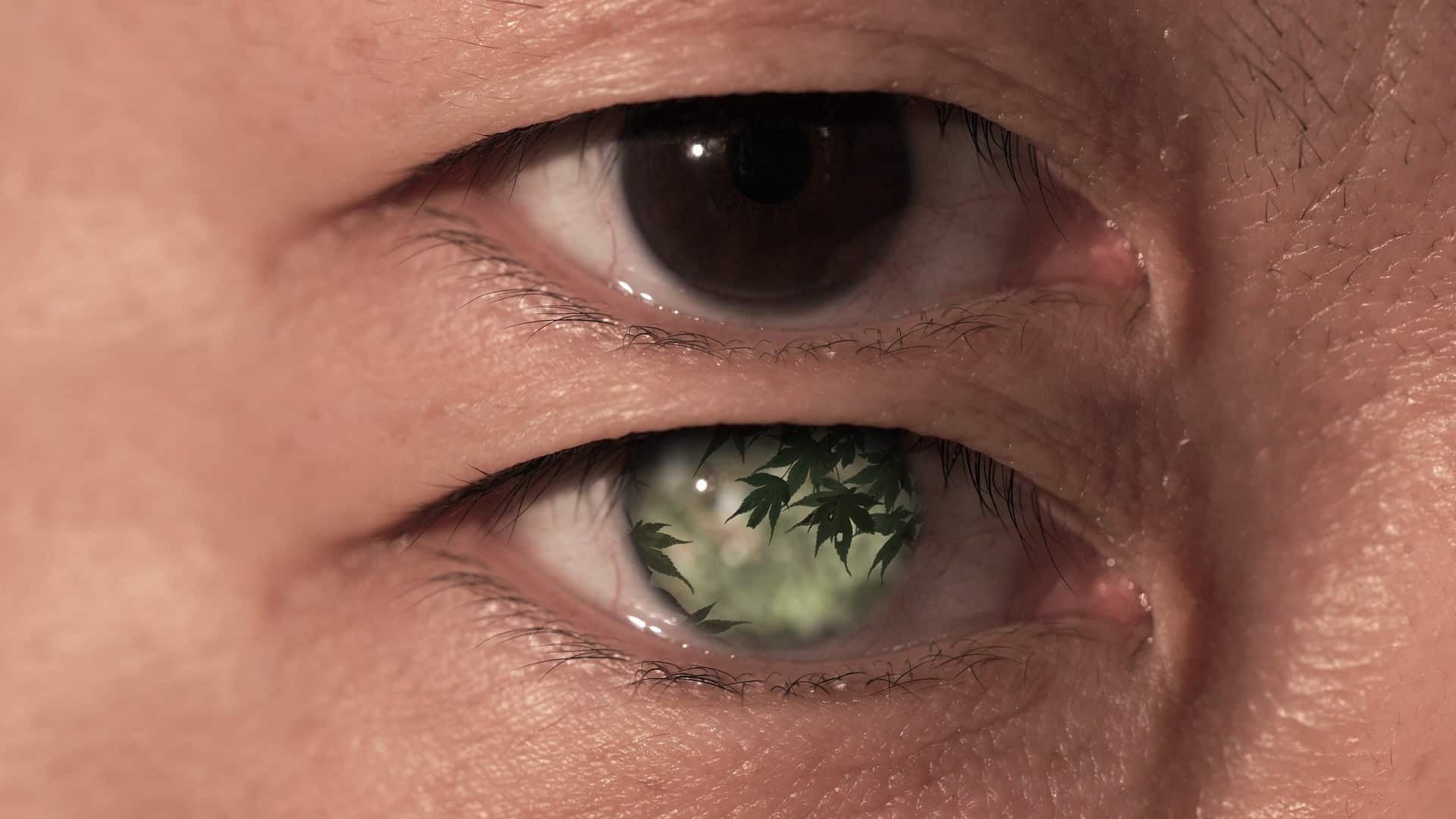

Further complicating this documentary-fiction conundrum – and thus of the reality being depicted – is the sudden presence of Li Tienlu himself in the film, now as an elderly man, recounting his life story directly to the camera (in one crucial scene, he is seen attending the fictionalised episode of his youngest son's funeral). As is evident then, “The Puppetmaster” is no objective depiction of the tumultuous history of modern Taiwan, but rather of history itself as seen through the prism of subjectivity, an impressionistic and dream-like portrayal of memories that have cumulatively distilled into a life. The aforementioned meta-cinematic techniques thus further complement the film's underlying themes of the past and present, memory and reality, and fate and free will, in which one acutely senses the push and pull of forces beyond one's control, both individual and collective. This indistinguishability of constructed drama and real life is something which comes across even more succinctly in the film's Chinese title, which literally means “Drama, Dream, Life” (in the film, Li goes on to form his own puppet theatre troupe and names it “Also Like Life”).

To underscore this subjective side of history, Hou and his cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing bathe the fictionalised episodes in warm and diffused light, further accentuated by muted and earth-toned colours. Rarely do we encounter close-ups; the camera is content to observe patiently from a distance, imbuing each image with a rush of melancholic nostalgia. Moreover, the images themselves are anything but narrative-driven: indeed, the film spends an inordinate amount of time showing us streaks of golden sunlight filtering through windows, the languid movement of a woman as she goes up and down the stairs, and the boisterous nature of a crowd as they watch a puppet performance out in the open. Such sequences highlight above all the sensory nature of memory, of how it is concerned more with the feel of something rather than the why or how of things (this becomes even more touching in light of recent news that Hou is now suffering from dementia).

This tendency of withholding also seeps into the performances, which, contrary to a character driven expressivity that we are all used to, concern themselves more with fleeting gestures and words. Thus, even emotionally heavy scenes, as when a young Li (played by Giong Lim) attends his father's funeral, play out with a certain restraint, as much influenced by the filmmaker's overall philosophy of life (and cinema) as by the rituals and traditions of a bygone Chinese era.

“The Puppetmaster” ends with an overtly symbolic image: the citizens of Taipei joyously dismantle abandoned warplanes for scrap metal in order to pay for Li's traditional puppetry performances, which they believe will please the gods and lead to Taiwan's liberation. This quest for freedom, following decades of quiet submission, intertwines with Li's own journey, who soldiers on with equanimity despite all the hardships in his life. It is then a fitting last image, a testament to Hou's oneiric and masterful evocation of Li Tian-lu's life.