How many times must a soul be slaughtered before its very essence dies? The violation of the human body and of its own psyche leaves indelible scars many of which will never heal. This dehumanization untethers the spirit from the vessel, eventually leaving nothing behind but a walking tomb. In Li-da Hsu's third outing a Girl posits that she “doesn't feel anything now”, brushing off the sheer horror and disbelief upon a Boy's face on what he has just heard. Such a flippant proposal of selling one's body at such an age would cause alarm throughout the globe but in “A Boy and a Girl” this is simply comes off as normal as morning coffee.

A Boy and A Girl is screening at Asian Pop Up Cinema

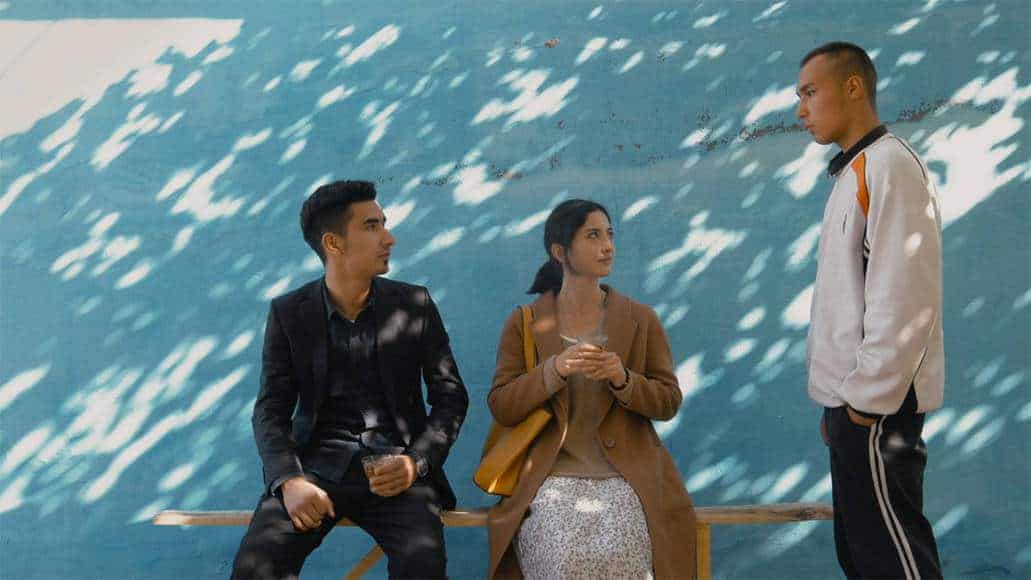

Showing zero interest in the world beyond his phone, a Boy (Yu-Heng Hu) lackadaisically stumbles through his own daily existence; headed nowhere fast, his abrupt temper in the face of his teacher and his Mother (Kris Kuan) does very little to disguise his contempt for his circumstances. One night he encounters a Girl (Chein-Lei Yin) in his secret hideout, texting on her phone and drinking a concoction named Little Devil which causes uncontrollable laughter and sleepiness. Taking her phone, he uncovers the Girl's shameful secrets involving their sports coach. Before long, the two concoct a scheme to escape their tragic adolescence together, leaving their toxic environments for good. When this plan falls apart, they turn to an even more abhorrent measure to raise the money for their departure.

Disassociated from themselves yet imprisoned in Hsu's ethereal periphery of modernisation, Hu and Yin exist in a state of permanent indifference and their grasp of their own humanity hangs on by a thread. Born as the by-products of an uncaring turbulence, neither one has grown up nurtured, their lives a dissonant fragmentation of circumstance and experience; for Yin in particular, her spiritual rupture has been so violent her only coping mechanism is found in substance abuse, and her nonchalant suggestion of turning to prostitution to fund their escape is all the more chilling for it. Hsu's film, with its slow pace, deliberated performances, and unnerving soundtrack, feels so meticulous in its desensitisation it becomes unavoidable, and any shred of hope slowly suffocates with each passing minute.

Check also this video

But just as “A Boy and A Girl” reaches its delirious apex, it awakens from its sombre stillness and descends into a more anarchic state. With Jack Yao's corrupt Cop catching on the teenager's exploits, the film's stylistic shift threatens to undo the microcosm-building it has painstakingly toiled over and instead spirals into a waking nightmare, the blossoming vitriol of their reality. Within the last third, Hsu's attempts to tie his dreamlike narrative into something cohesive hobbles towards the finish line, climaxing on a whimper instead of the cathartic release its central characters deserved. Mirroring neglect and abuse with a cold and unforgiving heart before cascading into trite silliness, Hsu's storytelling and direction becomes his own undoing; shaving half-an-hour of its runtime would have saved the devastating impact from becoming just as lost the film's victims.

Yet for all its faults, “A Boy and A Girl” is a visceral monument of woe, one where every breath and every glance tells its own story. Constrained by its minimalism, both Yin and Kaun reveal their character's truths in their expressions, their eyes speaking more than their words ever could. Yin captures the essence of a girl robbed of her innocence, denying her last ounce of courage to abandon her. For Kuan's Mother, that realization has long since been and gone, her face a map of despair, her words tainted with a forlorn longing for a sense of home. Both actresses deliver such understated performances as victims of spiritual, financial, and physical oppression at the hands of phallocentric selfishness.

Chen-ko Shin frames Hsu's bleak vision with such harmonious symmetry it feels deliberately at odds with the harsh realities evoked within; its muted yet immaculate tone however, exemplifies dreamlike abandon in world that is anything but harmonious. Coupled with Lu Luming and Tu Duu-chih's haunting ambience ,a permanent sense of foreboding fluctuates throughout the two-hour run-time, one that never eases up. Low frequencies strike an uneasy discomfort deep into the heart of those who experience it, its merciless desire to unsettle and unravel gives the film the cruel edge it so desperately demands and is all the better for it.

Hsu's haunting portrait of youth so violently torn from innocence is brutal and nauseating. Its damning portrayal of male primitivism and the carnage it unleashes upon its female victims, and of adolescence staring the grim realities of the world around them at a crossroads makes for a stomach-churning introspection. Clamoring onto a sense of direction in a purposeless universe, Hu's Boy is forced to leave an indelible mark on those around him, forced into a corner he never wanted to be put in. Hsu's world is cruel and unforgiving, threatening to shatter the lives of those deemed unlucky just to exist within its boundaries with little chance or escape. There's nothing redeemable here: those who hate seeing their authority challenged will bleed for it, and those vying for escape are doomed to remain trapped forever.