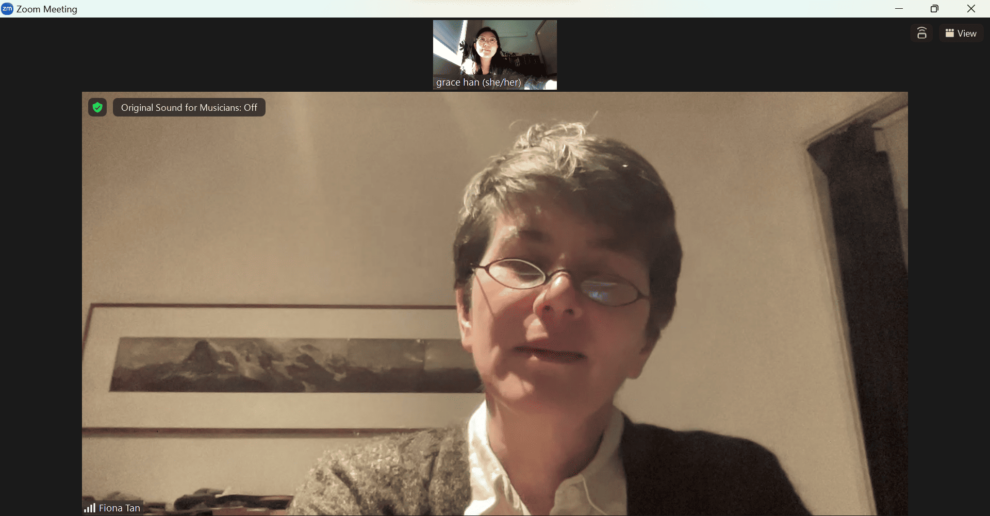

As a part of 2024 edition of the Museum of the Moving Image's First Look film festival, we spoke with Fiona Tan. With work in numerous international public and private collections including the Tate Modern, London, the Guggenheim Museum New York, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the Neue National Galerie, Berlin and the MCA, Chicago, MoMI will join the list with Tan's upcoming solo exhibition, “Footsteps”.

Fiona Tan's video installation, Footsteps, will be in the Amphitheater Gallery of Museum of the Moving Image in New York, NY from 13 March – 16 June, and the Artist Reception will be on Friday, March 15 at 5:30pm. You can find tickets for the exhibition here.

We had the pleasure to speak with Tan about her upcoming feature-length video installation: an amalgamation of silent footage ranging from 1895-1920s from Amsterdam's EYE Filmmuseum archive combined with letters from her father from the late 1980s, read aloud by Ian Henderson. Throughout our conversation, we spoke about writing letters, sifting through archives, and what it is like to walk down memory lane during a pandemic.

How did “Footsteps” come about?

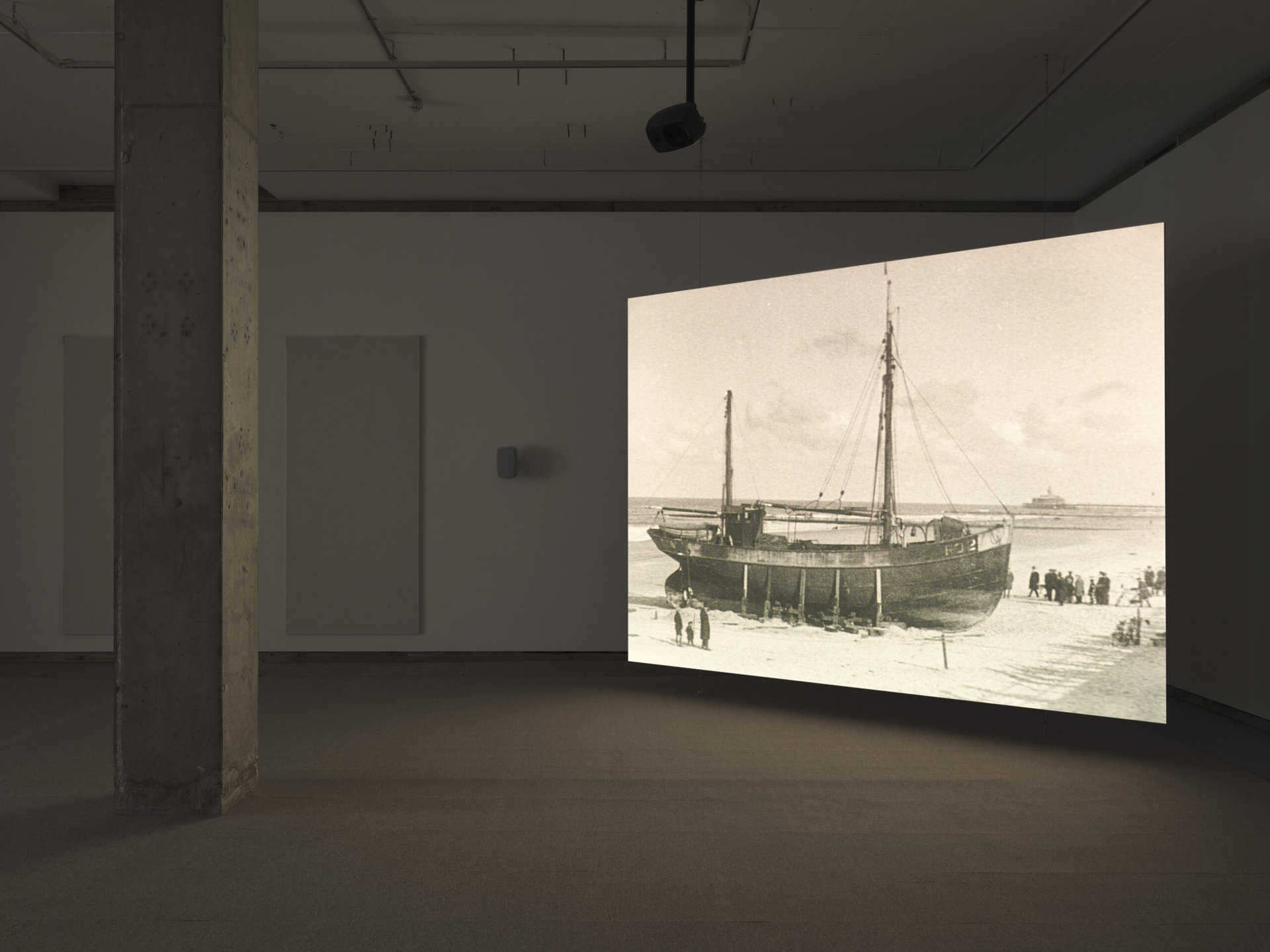

Fiona Tan: I was approached by the curators of the EYE Film Museum in Amsterdam to make a solo exhibition at EYE. This took place at the end of 2022. They also gave me the possibility to make a new piece, working with film footage from the EYE Film Museum archive, which is the national Dutch film archive. I had worked on occasion with this archive before, but this time was different, because they opened the doors wide; I had complete access – a once-in-a-lifetime chance.

I thought I should really try to make the most of this opportunity. This would be a large solo exhibition in my hometown; I moved to Amsterdam as a student and have been living here for 30 years. It felt like a time to stop, take stock and look back and reflect. What does living in The Netherlands mean to me? How have I come to understand this country and this culture? I started to look left, right, and center at the material in the archive, drifting and talking to the senior curator, looking widely without a plan.

When was the original commission?

I forget the exact dates. Both the new piece and my solo exhibition became delayed due to the COVID pandemic. That was such a strange time in our lives. And now on one hand, it's completely forgotten, while on the other hand, everything has irrevocably changed. There is a schism in time now, we recall events from before or after COVID.

Lockdown turned out to be quite serendipitous for this project. The EYE Filmmuseum collection building was closed to the public, but in order for me to continue researching and working on this project they arranged as an exception online archival access for me. This was wonderful because then I didn't have to go through someone or make appointments, I could just look at any time of day or night from my studio. In this way, I became well acquainted with the archive and its cataloging system, and was able to go much deeper in a more idiosyncratic way.

And the letters from your father?

During the Pandemic, I was cleaning up at home, as so many of us were. I thought that I'll finally clean up my desk. Actually, this desk I am sitting at right now, which has very deep, impractical drawers. In the back of one, I found these letters, handwritten on very thin paper that my father wrote to me in the years when I just moved to the Netherlands. I put them in order, sat down and read them.

And I was flabbergasted. I had forgotten so much. I was struck by how much thought he put into his letters, how much he was able to imagine aspects of my life, and how he was living with me from a distance. I was also very surprised to realize how much was simultaneously going on in the world at large at that time. It felt like I had stumbled across a gold nugget.

So putting them together…

I was excavating my way through this very large film archive, looking more and more at early Dutch film material. At a certain point, I had a light bulb moment: “What would happen if I combined these two things together?” “Footsteps” was born about nine months later. It was quite a heavy and difficult pregnancy, I have to say. (laughs)

For the silent film footage, there seems to be a transition from the Bruegel or Millet-esque countryside to this Vertov-like cityscape of constant labor.

It's in the history of the Netherlands. Looking at it now, the scenes we see in the old footage filmed in the countryside feel centuries-old rather than just 100 years old. To an extent it is. Wooden clogs are not a recent invention, and for good reason. They keep your feet dry, which is something you need in the Netherlands where it rains so much.

I also wondered: Why is it I am so struck by and so drawn to these images of labor? There are several reasons for this. Firstly, one of the things I love most about this material is its physicality. The quality of the grain, the lighting, the simplicity, the frame – it all somehow strengthens the corporeal, visceral, physical nature of the actions we are witnessing. It was also in such great contrast to what I myself was going through at the time. Here I was, alone – involuntarily so due to the pandemic – sitting motionless behind a computer screen. Life in the late 19th, early 20th century was so communal – almost no shot is of one person on their own. Heaps and heaps of people, whole villages on a Sunday, mending fishing nets, cutting hay. I also noticed child labor and women doing very hard work alongside men. And also workers loading ships on the docks, the extent of the harbor, its wealth, imports of tea and coffee and teak wood from what was then known as the colonies. This was also part of Dutch culture and economy.

There's an echo of isolation too, through the letters read aloud in the voiceover – with your father and yourself separated across the globe.

These bridges span time and space. It's not just geographical, but also temporal distance between when he wrote his letters and the time now. I was constantly negotiating that. It is difficult to explain in words, so talking to you now, I make gestures with my hands – “the small” and “the large”, the personal and the global. My father flips in one sentence from something “small” – like his pets at home – to something “large” – like Australian politics or global events: Russia under Gorbachev, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, the Tiananmen Square uprising in China. I thought the way he equally cared for his pets at home and Gorbachev on the other side of the world was important, worthwhile, valuable.

Judging from your father's letters, you also seemed to be an astute respondent.

We had quite a clear rhythm. I used to write every Thursday. He and my mother would write every second week. Remember it was our only mode of communication; there was no Internet in those days. We would telephone twice a year, for Christmas and my birthday. However, my father didn't like to speak on the phone. On Christmas Day when I rang, my father would wish me a “Merry Christmas… and now here's your mother.” And he would hand the phone over to my mother.

This brings up the matter of the voice.

I originally planned to record the voiceover myself, similar to a previous film I have made called “Ascent”. I recorded a rough version of the voiceover for use in the editing. Quite quickly however, it became clear that that wasn't good enough. For the editing you need the right timing and the right intonation for the emotional meaning to come across.

Ian Henderson is a great actor, whom I had worked with before. So I contacted him with the idea that he could coach me as a voice actor. But in preparation for this, I wanted to record his reading of the voiceover first. I remember sitting there in the sound studio and thinking, “he's creating this character – the father – making him real. It's so moving, warm, and intimate; I am going to struggle to do as well as he does.” Quite quickly I decided that it would be better to work with Ian's wonderful voice. Much to his own surprise and amusement, I suspect, my father has a Scottish accent now.

So Ian Henderson doesn't sound like your father at all.

Not at all, which is actually quite nice, because this means there is another kind of distance incorporated into the piece. The voice is its own character now.

What about the Foley for the rest of the film? You used entirely silent film footage, but we still hear subtle sounds – like the clucking of chickens and moving machinery parts.

The sound design took a lot of work and time to figure it out. As all the footage used was silent, all of the sound has been conceived, designed and composed in the sound studio. It is like music; it has an ebb and flow across long sequences of scenes. And I cannot overemphasize sound's importance for the piece. Sound is always the forgotten brother in cinema. It's much more important than you realize, because it's so subconscious. For “Footsteps”, we strove for a soundtrack that feels very natural, even though it actually is not at all.

And the rhythm of the piece. It lulls the viewer into a trance, but then small details – like footage of child labor or mentions of a major global event – jerk us out of it.

Yes. And there are also the insertions of brief moments of black, which function in the montage in several ways and keep you as a viewer on your toes.

What was your favorite part of working on the film?

That's a really tough one to answer. The editing was an extremely long process requiring consideration amounts of patience and perseverance, but also really engaging and rewarding. Working on the sound was also nerve-wracking and taxing but also exciting. I think all of it, really. Making the most of an unusual and challenging idea and then seeing it all come together.

I also heard that this piece originally premiered at Berlinale, but we're seeing it as an installation at MoMI. How do you feel about your upcoming New York reception?

The cinema version of “Footsteps”, entitled “Dearest Fiona” premiered at the Berlinale last year. In the cinema it is slightly longer. It has been a few years since I have been to New York, I am looking forward to it!