Since the beginning of his career, Hirokazu Koreeda became recognized for his films representing the family cinema genre—intrinsically linked with the favorite of Western critics among Japanese filmmakers: Yasujiro Ozu. This was already the case with Koreeda's 1995 debut film, “Maboroshi no hikari”, a visual meditation on loss and the passing of time, told through the eyes of a single mother who has just lost her beloved husband. Since the early 1960s and the death of Yasujiro Ozu, Western critics seemed to be engaged in an excruciating quest to find a new ancestor to Ozu's poetics of cinema—and finally, there was one; Koreeda became the new Ozu.

The similarity is there—a contemplative approach towards the mundane which translates to something more transcendental; a patient gaze onto the bonds of the family set against the backdrop of a modernizing world and changing traditions; or a talent to put things into motion and seek substance within the most trivial things, amidst the transience of the world. All that is quite true, but Koreeda's understanding of cinema includes the critique of systemic power that Ozu's narratives lacked.

Even though Koreeda's films represent the family drama, they also stand as focal and critical points of view against the mainstream narration of what constitutes the figure of family—by challenging the common understanding of familial ties in Japan, he foregrounds his position as a distant observer. By revealing different representations of Japanese families, he confronts the idea of a homogeneous society and, thus, reveals the facade of systemic and familial failures. This is essential because it is family that constitutes society, and becomes its primary feature of organizational structure.

It's not only the chain of blood that determines the being of a family, as he demonstrated in either “Like Father, Like Son” or “Shoplifters” to name a few. In that sense, Koreeda has made himself a poignant critic of the Japanese landscape—scrutinized through the lens of family. His attempt to sketch the trajectory of Japanese identity in a modern context exists within the proximity of the masters of Taiwanese New Cinema, early Hou Hsiao-hsien's work or Edward Yang's films, or Nagisa Oshima's body of work, especially if we think of scam or borrowed identities as recurring representations.

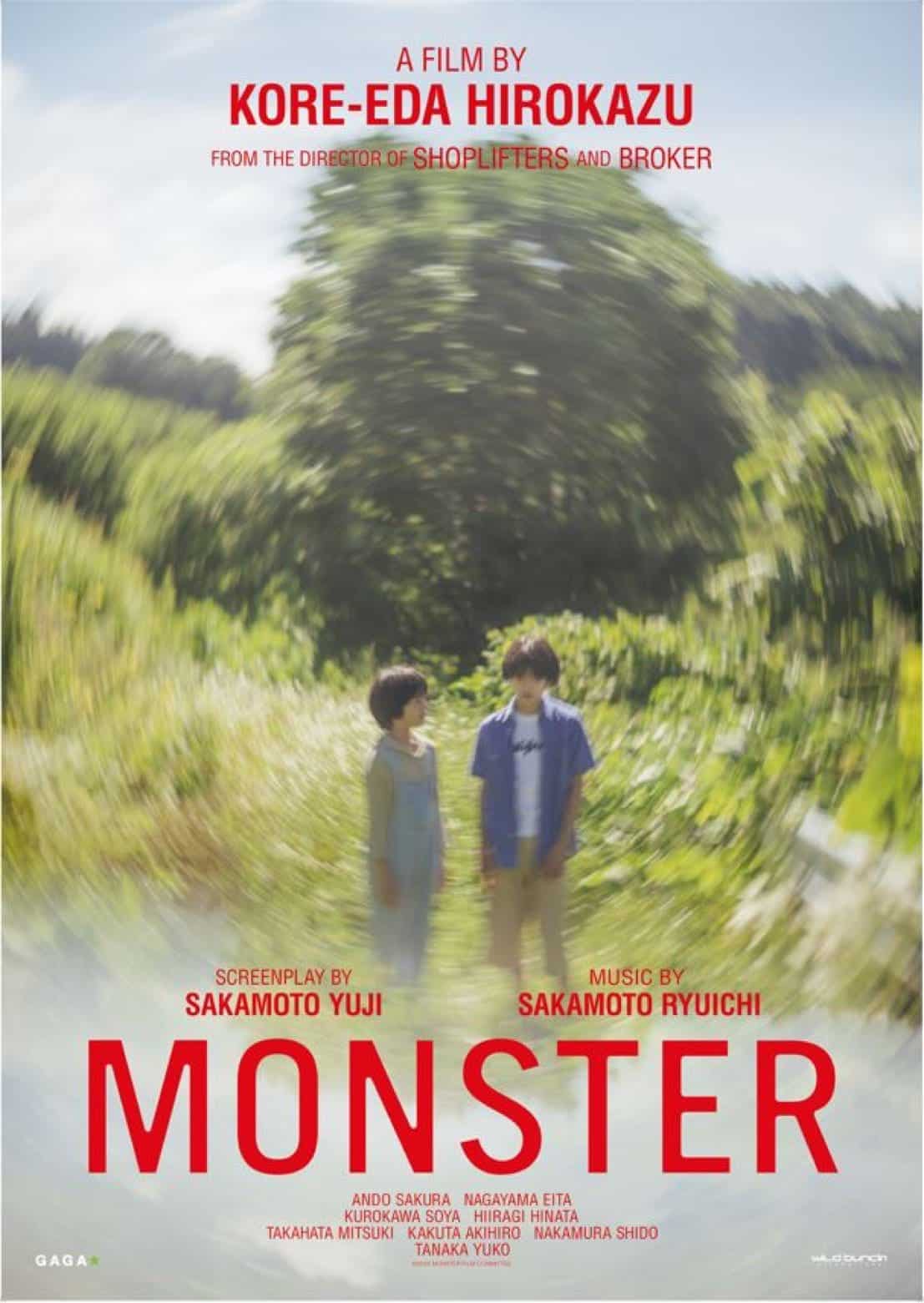

“Monster” premiered in the UK cinemas on March 15th.

Koreeda's latest piece, “Monster”, continues to outline the context of the Japanese family inflicted within the systemic dynamics, but it is, perhaps, his most sensational work to date. Told through three different perspectives, it pivots around a young boy Minato, and the ambiguity of his relationships—that with his mother, his teacher and school environment, and his friend, Yori. The idea to split the narrative into different points of view enables Koreeda to untangle the peculiarity of the setting—the frame of Japanese institutions in which systemic pathology unfolds.

The less we know about the structure of the film, the more we can immerse ourselves in the meticulously crafted storytelling, encapsulated through precise scriptwriting (Yuji Sakamoto) and editing (by Koreeda himself). We embark on a journey—through stories-within-stories, white lies, or narratives that fail to withstand. It's a road filled with easy judgments, a moral quest within ourselves, as we constantly question the legitimacy of the characters or their testimonies. “Who is the monster?”, Minato and Yori sing as a playful song, but the real answer is hidden within the generational traumas that the film conveys.

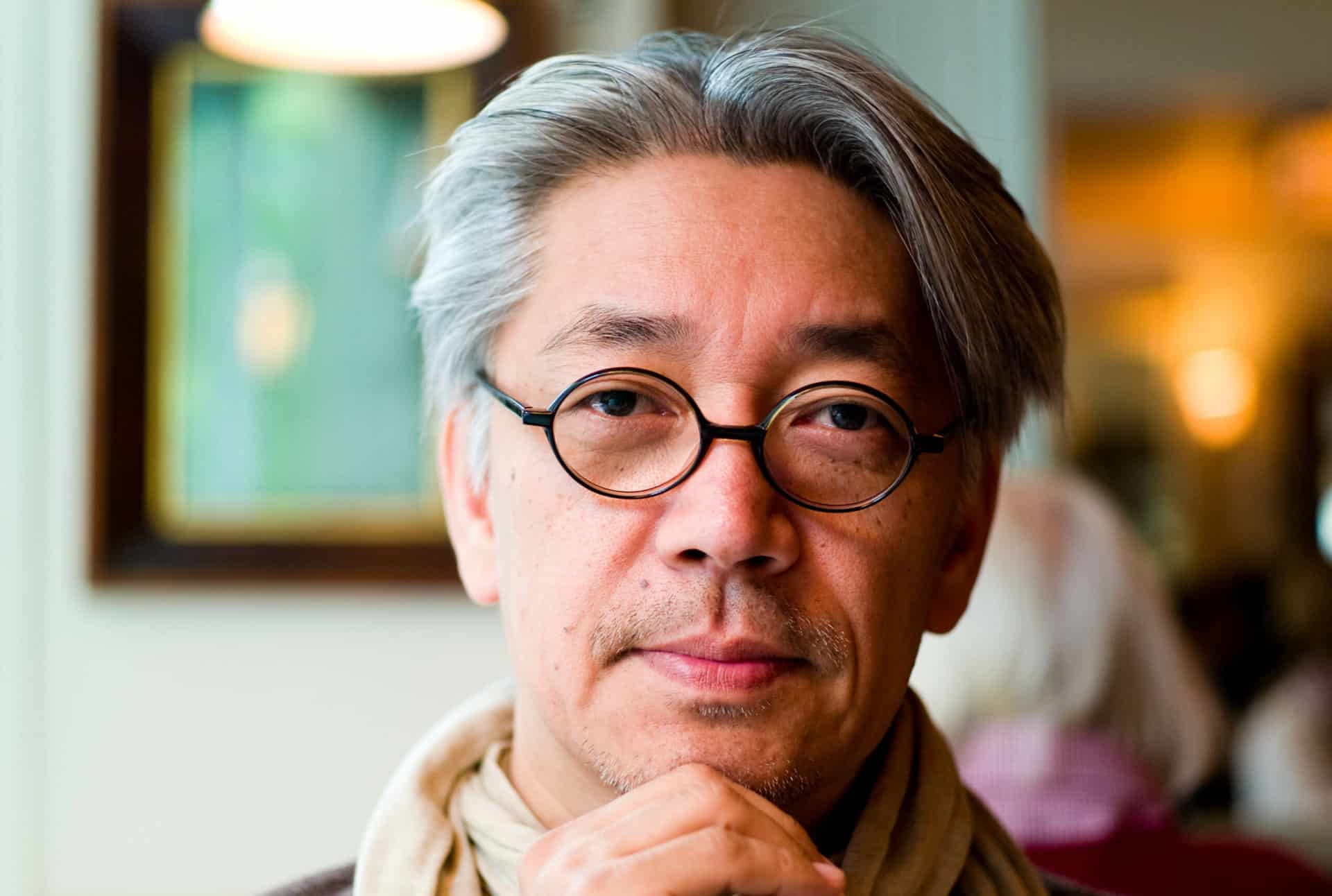

We speak with Hirokazu Koreeda about his approach to storytelling in “Monster”, the process of finding the right angle for the story, his collaboration with Yuji Sakamoto (whose script was awarded at Cannes), systemic monstrosity in Japan, working methods with children, maintaining rhythm through editing, and the memory of Ryuichi Sakamoto and importance of his music for Koreeda's films.

Lukasz Mankowski: It's the first time since “Maboroshi no hikari” that you worked on a script that wasn't written by you. I assume it wasn't the case that Yuji Sakamoto gave you the script and that was it; that you needed to go through the changes and tweak the story until you felt it was what you were looking for. What did this process of adapting someone's script look like?

Hirokazu Koreeda: Indeed, it wasn't a situation in which I was handed a script and someone said, “Here, direct this!” I came across the story in December 2018 and it took us three years during which we would exchange thoughts [with Sakamoto] back and forth to eventually finish the screenplay the way it appears in the film (the initial draft would equal the running time of three hours). By the time I started filming, it didn't feel that different than having it written by myself. I was so engaged in the process of writing, that I had a sense of being in it from the start; not having complete control over something felt just right, as a sense of distance seemed somewhat convenient. Aside from that, I think that the style of storytelling wasn't something I could come up with on my own—in fact, I don't consider myself a storyteller that much.

Why's that?

In most cases, the stories that I write are slices of life. I focus on a certain sequence of events in someone's life but I try not to show what happened before or what can occur afterward. Instead, I rely on the viewer's imagination—I want my audience to open up to the possibility that certain things can happen. It's not storytelling; at least, I wouldn't call it as such, as in the majority of the scenes I write I don't rely on the power of presentation.

How did it translate to your work with Sakamoto?

Sakamoto brought something new for me—a real momentum and this drive to keep the story moving to find out what happens next. Inasmuch as there's less of a slice-of-life approach that I was preoccupied with in my previous films, “Monster” stems from something different—the strength of the narrative. That's why I think the whole collaboration with Sakamoto turned out as a positive experience—among the screenwriters active in the Japanese film industry, he is the one I respect the most. In a sense, our stories share a common ground—we're both preoccupied with neglect or patchwork families—but we deliver them in a different tone; it's like we're breathing the same air, but exhaling it a bit differently. That's why I always wanted to make a film with Sakamoto, simply because I can't write like him. His ability to change tones and build multi-layered characters is something that I always looked up to, as I think I never had that.

Your stories have dealt with multiple perspectives in the past, but this time around, the “Rashomon”-like structure clearly translates to the escalation of tension in the story.

The structure of the storytelling was already there in the plot. The idea came directly from Sakamoto who wrote the script. When I read the initial version, I recognized the “Rashomon”-like structure. The idea, however, wasn't to limit to the fact there are just three different contrasting perspectives, three truths. I wanted to go beyond that by giving the boys the agency to escape the structure. In the context of storytelling, they are released from this journey, which is about a quest to hunt down the monster.

There are three perspectives but also different words that mean the same—monster. In each of these storylines, you include a different word to address a systemic monstrosity. These are: monstā, bakemono, kaibutsu [the Japanese title of the film].

But the translation in English remains as ‘monster' in all three of these words, right?

Correct.

All three words grasp nearly the same but have their nuances as well. In Japan, there is a word used to address bad parenting—‘monster parents'. Everybody knows it, that's why the teacher uses the word monstā in the context of the school dynamics. Then there's a child in the hospital, who uses the word bakemono in a conversation with his mom. In that particular setting, the kid wouldn't probably use kaibutsu in a conversation with their parent. All three words slightly differ from each other. They bring a delicate nuance and highlight a context. But in terms of translation, we had to go for a unified ‘monster'.