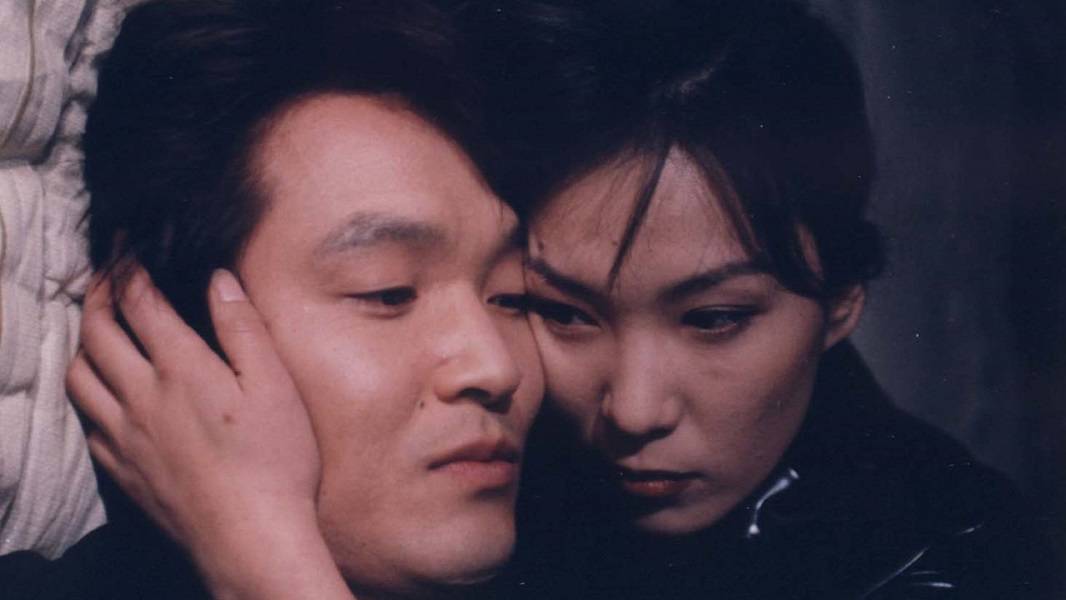

Green Fish (1997)

Mak-dong has just been discharged from the army and returns to his hometown and his shuttered family that includes a single mother, and three brothers, one alcoholic, one handicapped and a very reckless one. While on the train, he helps Mi-ae, a lone woman who is being harassed by thugs, only to find himself without his belongings, beaten and out of the train, but with her red scarf in hand. As he revisits his town only to find that the fields he used to know have turned into a newly-built town, he receives a call that eventually reacquaints him with Mi-ae, who turns out to be a singer and the girlfriend of a crime boss, Tae-gon. Having no alternative, and after getting beaten again, he “allows” Tae-gon to give him a job in a parking lot. Soon, he finds himself being a regular member of the gang, and a favorite of the boss, to the irritation of the previous favorite, Pan-su (Song Kang-ho, in his first speaking role), while he learns of Mi-ae's tragic situation.

Lee Chang-dong's characters are characteristically anti-heroic, but he seems to justify them due to their background. Mak-dong's family is completely shuttered, as so eloquently portrayed in the picnic scene, and with no kind of prospects in life, his association with the organized crime seems like the only exit from his misery. The same applies to Mi-ae, who seems to think that she has no value apart from her association with Tae-gon, and cannot get away from him despite her repeated efforts. Tae-gon also finds himself in binds, as, per his own words, he has crawled to the place he is now, but his past and particularly the people he had to “service” to get where he is now, do not seem to let him go. Eventually, these three miserable lives form a triangle that leads to an inevitable clash to a shuttering conclusion of a dead-end story.

Lee creates a dog-eat-dog world where kindness, compassion and even hope do not seem to exist anywhere, and in that fashion, induces the film with a distinct but not hyperbolic, melodramatic essence. This sense finds its apogee in four scenes: the aforementioned with the picnic, the one where Mak-dong speaks with his handicapped brother on the phone (where the film's title comes up), the one in the abandoned building, and the one in the finale, which manages to close the story with a somewhat hopeful, but still melancholic, note.

The film, despite its unusual premises, was a commercial success and became the eighth highest-attended South Korean film of 1997, kicking off Lee's career in the best manner. His focus on the “marginalized” people from society and on a secondary level, of the handicapped, begun here, but it would not find its apogee until later in his career. However, the unusual for his film style commercial success, would never abandon him.

Similar in theme, but quite different in presentation was Lee's next film, “Peppermint Candy”. Regarding the similarities of the two films, the director states: “There's no question that “Green Fish” and ‘Peppermint Candy' draw on the political and economic problems of Korea. But they weren't my main focus. My main interest has always been human beings. I believe film is the best medium to show something about human beings. But people can't be separated from the environment (including the political and economical reality) that surrounds them. Man is affected by his reality, and in fighting against it finds meaning in his life. Those are the kinds of things I wanted to show“. (Source: http://asiancinefest.blogspot.gr/2008/05/acf-108-lee-chang-dong-e-interview.html).

Peppermint Candy (1999)

The story actually starts with Yong-ho's suicide, and then moves, in segments, backwards in time, in order to present the reasons that led him to this extreme act. Many of them coincide with some of the most important incidents in S. Korean history, as the student's demonstrations that led to the Gwangju massacre. Furthermore, the story around Yong-ho's first love, Sun-im, who loved him dearly is also revealed as the story progresses, proving the impact it had on him.

Lee Chang-dong presents a melodrama that stands apart from the plethora of similar productions due to its intense political element. In that aspect, and in order to comprehend the story fully, one should have certain knowledge of the country's history, since Lee assumes that his audience is familiar with the sociopolitical background of each segment. Apart from that, the reverse chronological order is artfully established, and does not confuse or tire, in an achievement that benefits the most from its elaborate editing. The character's depiction and analysis, and particularly of the two protagonists is another point of excellence, since all of their actions become utterly comprehensible and even justifiable. I also enjoyed the way Lee uses trains, which appear in almost every important moment of the film, with the purpose of reminding the way Yong-ho committed suicide, and as a medium of visualizing time.

The film was again a success, both commercially (the ninth highest grossing domestic film of 2000) but particularly in the festival circuit, as it screened and won awards all over the world, along with the 2000 Grand Bell Award for Best Film. His collaboration with Sol Kyung-gu and Moon So-ri, which was quite tense as we are going to see later in the article, began here and continued for one more movie.

The article was initially published in Hancinema