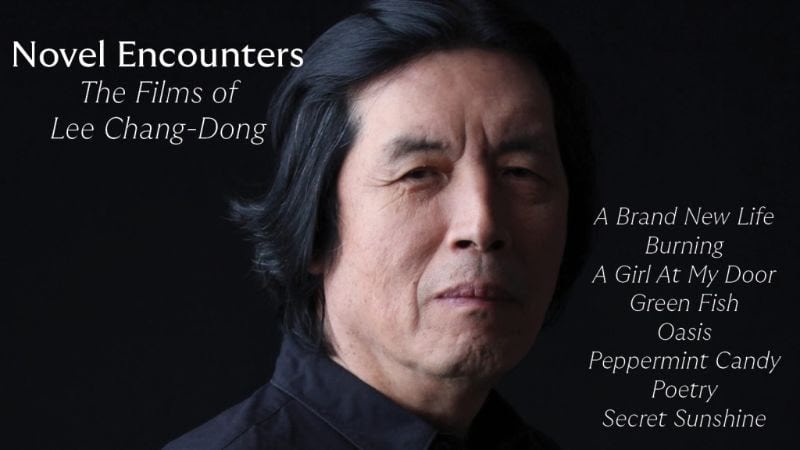

Considered by many as the greatest contemporary Korean filmmaker, Lee Chang-dong is a truly rare case in the peninsula's cinema, both due to his impressive filmography and the rather unusual (unconventional if you prefer) path he followed in his life, which brought him from a teacher's position to the seat of the Minister of Culture. Let us take things from the beginning though.

A Retrospective of Lee Chang-dong's movies titled “Novel Encounters: the Films of Lee Chang-dong” will screen at Metrograph, beginning April 5

Lee Chang-dong was born July 4, 1954 in Daegu, North Gyeongsang Province, a city considered by many as the most conservative (and rightist) in the country, to lower middle class parents, who were leaning to the left, particularly his father, who was an idealist who never had a job, thus forcing his wife to work hard in order to support the family. On the other hand, his family came from noble class of the old Korea, and this contradiction, of growing up in a ruined, ex-noble family with communist ties shaped his character quite significantly.

He graduated in 1981 with a degree in Korean Literature from Kyungpook National University in Daegu, where he spent much of his time in the theater, writing and directing plays. After a period of teaching Korean Language in high school, he established himself as a renowned novelist with his first novel Chonri in 1983. In 1992, he won the the Hanguk Ilbo Munhak (The Korea Times Literary) Prize for the short story collection “There's a Lot of Shit in Nokcheon”. However, and despite the fact that he became famous through his work in literature, his work in theatre was much more extensive, and actually gave him much “equipment” that later helped him as a filmmaker.

Regarding his entry to cinema, I will quote his own words. “Actually at that time, I was in considerable doubt both as a writer and as a person stepping into his late 30s. Perhaps you could say I wanted to punish myself. And so I wanted to do something like hard physical labor, and what I chose was to work as an Assistant Director. Director Park Kwang-soo had just suggested that I do the scenario[script] for “To the Starry Island”, and I made a kind of ‘ deal' with him to use me as an Assistant Director. Of course at the time, my filmmaking experience was nonexistent and I was in no way qualified to AD. In a way what made me a director today is very much indebted to Park Kwang-soo's gamble to use me as First Assistant Director“.

Park, who in 1993 had become the first Korean filmmaker to find his own production company, also came from a background in another medium, painting. Actually, the initial reason for their acquaintance was the fact that Park wanted to meet Im Cheol-u, author of the novel “To the Starry Island” was based upon, and Lee, who already knew him, made the connection. Eventually, Park asked Lee to make the adaptation, and after rejecting his first revision because it was not cinematic enough, he accepted the second and even asked Lee to become one of the assistant directors in the film. On Lee's first day on set, the first AD was fired and he took his place, since he was the oldest among the other assistants. (Source: Kim Young-jin, “Lee Chang-dong”, Seoul, Korean Film Council, 2007).

To the Starry Island (1993)

The film moves in two axes. The first one occurs in the present where Moon Jae-goo attempts to bury his father's body on the island on which he was born, with the help of his friend, Kim Cheol, a poet who lives in Seoul. Due to his father's past though, the inhabitants of the island refuse to allow him to do so, despite the fact that he has already bought a plot. Kim Cheol tries to persuade the villagers, while he reminisces about his past, with his memories forming the second axis.

This arc revolves around Ok-nim, a simple-minded girl who is forced to marry an older man, a woman with shamanic powers, and another one who is called “Easy Lay” by the rest of the population due to her promiscuousness. The main point of interest though, is Moon Deok-bae, Jae-goo's father, with the story painting an image of a rather despicable man, who is indifferent towards his son and his sick daughter, unfaithful to his wife, with his behaviour becoming even worse as time passes.

Eventually, and during the war in Korea, the army arrives in the island, and everything changes as the true character of the islanders is revealed, with Moon, once again, being the worst.

Not much of the style that characterized his later works can be found in here, since Lee was quite overwhelmed by the whole experience. However, the film's significance lies with the fact that it is his only work that refers to the Korean war, in a story that presents a comment regarding both the North and the South Forces, although the critique on the latter is much harsher.

The film had another significance in Lee's career, since, during the shooting, he and Dong Bang-woo (he had a small part in the film), whom Lee knew from the theatre since 1982, became good friends. Myung would eventually produce Lee's first directorial work.

Before that though, Lee wrote another script for a movie Park directed, “A Single Spark”. During this process, in 1995, disaster struck. His laptop crashed and Lee lost all his data including two novels and the biography of Park In-cheon, CEO and founder of Kumho, named “Teneciousness”. Lee had to rewrite everything from scratch (including the bio) in a process that exhausted him.. (Source: Kim Young-jin, “Lee Chang-dong”, Seoul, Korean Film Council, 2007).

Nevertheless, his second collaboration with Park Kwan-soo, was released in November 13, 1995

A Single Spark (1995)

Lee's second work as a scriptwriter was a very political film, which focused on Jeon Tae-il, a worker and workers' rights activist who committed suicide by burning himself to death at the age of 22, in protest of the poor working conditions in South Korean factories.

The story revolves around his life and in a secondary axis, five years after his death, in 1975, when law school graduate Kim decides to write a book about Tae-il, in the midst of the worst period of President Park's regime, when political activism was punishable by death. In the present timeframe, Kim, who is also an activist, hides in a room rented by his girlfriend, while he spends most of his days visiting the places Tae-il have been, with the film changing arcs each time, to present the experiences of the deceased in the particular location. Through these flashbacks, Park depicts the awful working conditions in the factories in Seoul, where tuberculosis due to poor or non-existent ventilation, and the enforced injections of amphetamines to keep sleep-deprived workers awake for days in a row in order to work overtime without proper compensation, was the rule.

Tae-il, working as a tailor in one of these sweatshops is “enlightened” after reading a book about labor law and becomes an activist. After a number of efforts to alarm the authorities of the situation in the factories, he turns to the press, with the publication of his stories becoming one of the few successes he experienced until his suicide. In 1975, Kim also has to deal with the authorities, particularly through his girlfriend, who finds herself a victim to violence due to her activist actions.

Lee's script presents the story of Kim with thoroughness and distinct sympathy towards his subject, and while the movie takes the side of the activists, he does not fail in portraying all aspects of the concept, even involving some ill practices of the far left, of which Lee Chang-dong had some experience, as we mentioned in the beginning of the article.

Lee describes his experiences on the sets of these two films and the path that led him to his directorial debut as such: “How I came to be a director results from a few unexpected coincidences. Because I wanted to ‘punish myself' I worked very hard on the set, and it seems that made a good impression on some of the staff and cast members that I didn't expect. After that, those people kept suggesting that I become a director, and eventually helped me to debut as one. Of course, it's not as though I had never had the desire to become a director. I had always been curious about the distance between film and reality, and had questions about the apathy of movies (whether commercial movies so-called art films) that were growing farther and farther detached from reality. I wanted to make films that closed the distance a little, between film and reality”. (Source: http://asiancinefest.blogspot.gr/2008/05/acf-108-lee-chang-dong-e-interview.html)

Apart from Dong Bang-woo, whose 1996-formed production company East Film would eventually produce Lee's debut, Moon Sung-keun, who starred in both films, and Shim Hye-jin who starred in “To the Starry Island”, agreed to participate in Lee's first film, along with Yu Yeong-gil, who was the cinematographer in both.

Lee Chang-dong describes the process that led him to “Green Fish”: One year before making “Green Fish”, I moved [home] to Il-San city, a newly constructed apartment complex at the outskirts of Seoul. The area, previously a general Korean agricultural village, following the wave of urbanization was transformed into one of the biggest modern cities erected near Seoul. In other words, one might say that it became an exemplary space symbolizing the thirty years of continuous modernization and economic development in Korea. As my life unfolded as an inhabitant of this modern space, I started to ask myself questions: the people who lived here before the new city took their living space – what were their dreams? And how could we retrace the memory of them? “Green Fish” can be considered as a transmission of these questions into film.