The 2024 edition of BISFF was as indicative as a festival could be, both for the short film industry and cinema in the region overall. For starters, and as we mentioned many times before, the Korean short films nowadays seems to have made significant progress, to the point that it can be more interesting searching among them than in the feature ones. Titles like “Eyes”, “Hunted Owl Family” and “I'm Here to See The House” highlight the fact in the most eloquent fashion. At the same time, and as we move further in Asian, the rather interesting mixture of documentary and fiction comes to the fore, occasionally finding its apogee in some of the titles featured here, with reality proving, once more, that provides better scripts that people's imagination.

Without further ado, here is a rundown of all the titles we reviewed for the 2024 edition of Busan International Short Film Festival Reviews, starting with the Korean ones, and continuing with the rest of Asia. By clicking on the titles, you can read the full interviews.

1. Luna (2023) by Kim Hye-jin

The comments Kim Hye-jin wanted to make are quite evident. The issue with unwanted pregnancy and the issues women who want to have an abortion face is the central one, with the doctor sequence showcasing both them and the solutions. At the same time, Kim seems to state that one has to be calm in order to face these situations, and having a way out, in the case of Luna through music, definitely helps. Having a good friend and someone to talk to also helps, with her colleague and her employer taking up the roles respectively. The latter also embodies another comment, about single motherhood and the problems trying to raise a kid and having to work presents, cementing the overall context here.

2. Eyes (2024) by Nam Hyok-young and Choi Yoo-jae

Nam Hyok-young and Choi Yoo-jae have shot a very interesting animation, which focuses on the concept of bullying, how unfair it is, how it generates, and how can the victims overcome it. Through a surrealistic approach that works quite nicely here, they seem to suggest that one must find the strength to move on within themselves, and that managing to overcome depression through perseverance can eventually have life- changing results. Granted, the comment is somewhat romanticized, but the message still echoes realistic and is well-communicated.

3. Slaughter (2023) by Yun Do-yeong

Through an approach that combines fiction with documentary, and with an occasional tension that frequently points towards the thriller, Yun Do-yeong makes a rather pointed comment about toxic masculinity and patriarchy. That the men are still expected to be the main financial supporters of their family becomes quite evident from the fact that most of the people who work in the slaughterhouse are there because they have to provide for their families. Sang-woo and Kumar are prominent samples, but the case does not seem to be particularly different with the rest of the employees.

4. Hunted Owl Family (2023) by Jin Roh

Not only is “Hunted Owl Family” a spy drama, but it also works as a silent film. Not relying on any dialogue, the burden to carry the narrative as well as the conflicts within/between the characters lies on the actors, the images and the sound. Luckily, all of the mentioned aspects succeed in making “Hunted Owl Family” work as the genre blend it aims to be, but also make it quite special even within the often very experimental landscape of short features in general. Starting from the opening scenes introducing each of the family members, the combination of lighting, colors and the overall design choices give a very distinct noirish vibe, which is also confirmed by the setting of the remote hotel as a metaphor for the family in hiding and having lived in isolation for some time. (Rouven Linnarz)

5. Shadowy (2023) by Kim In-hye

Kim maintains this atmosphere with the use of dark lighting, in a piece with an all-round bleak outlook, in a way Hirokazu Koreeda mastered with “Maboroshi” (1995). There is barely a smile, apart from those designed to taunt us as an outsider looking in. It is, therefore, a very slow and angst-ridden watch to make your way through, though is the perfect short in that it captures the essence of a single emotion. (Andrew Thayne)

6. I'm Here to See the House (2023) by Junh Yoon-ah

Jung Yoon-ah directs a film where everyone involved are on the right. Seon-ok feels the pressure from all sides, with the payment of the loan, the tenant who refuses to cooperate, a daughter who is demanding what she deems is her right and a husband who is about to become unemployed. Ja-hyun feels a similar pressure, having to find another apartment to move on while her little daughter still goes to school, and her husband never seems to be home. Furthermore, the actions of Seon-ok, which can only be described as hostile after a point, make her whole situation even worse. Lastly, Min-gyeong feels the unfairness as she is just asking what her elder brother got from her parents, who never actually even think of doing so before she suggests it.

7. Heaven's Door (2021) by Kim Gyu-tae

Kim Gyu-tae has some interesting ideas, like using genre filmmaking to make social comments, while he evidently knows how to create a captivating atmosphere. At the same time, however, the 28 minutes of the short are definitely not enough for his ambitious purpose, with the first past getting almost completely lost. Hopefully, if he gets the opportunity to shoot a feature in the future, he will be able to achieve his goal in much better fashion, as he seems to have the knack for it.

8. Invisible (2023) by Hong Da-ye

Hong Da-ye shoots a film that thrives on its atmosphere, with her creating a sense of mystery underscored by the notion that something sinister will eventually happen. The voyeuristic shots of DP Kim Jeong-eun add much to this sense, as does the tension that permeates the short, which actually becomes more palpable as time passes. The scene with the locals and its implications, but most of all, the very finale cement this approach, while adding a very appealing slight ambiguity about what is exactly happening. The whole approach is also heightened by the cuts of editor Yoon Sang-mi, with their suddenness adding to the aforementioned.

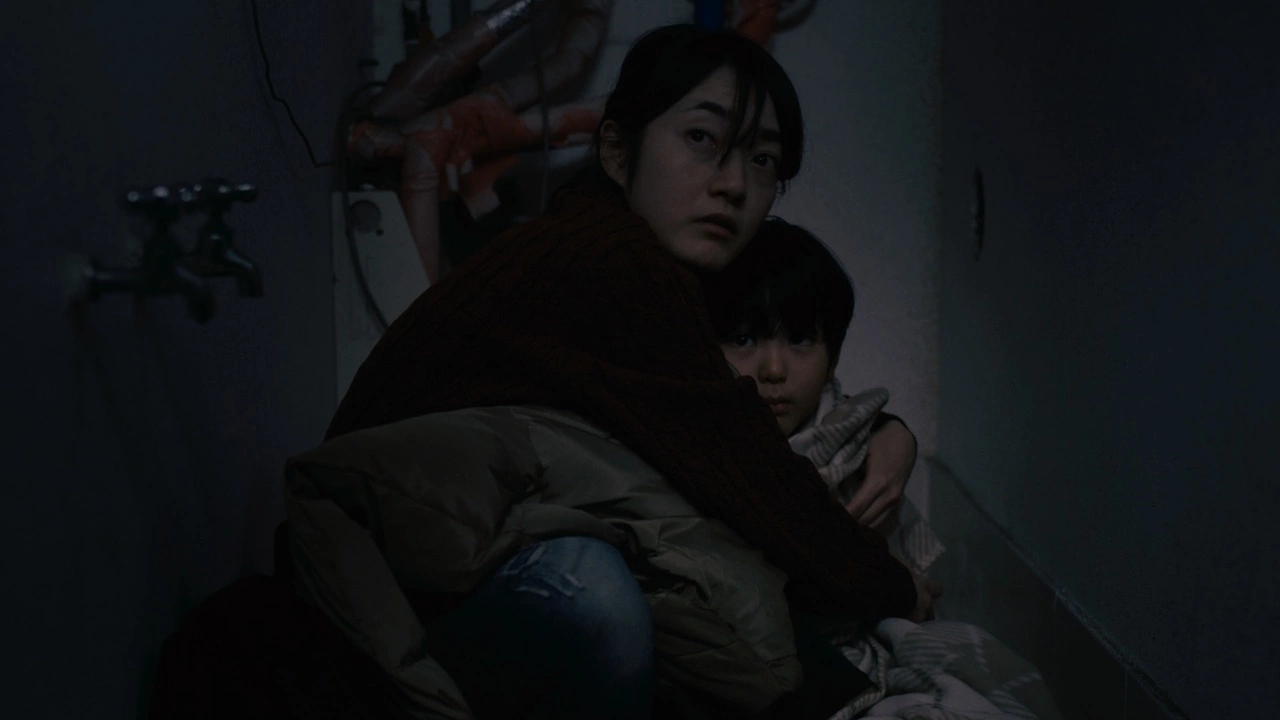

9. Hide and Seek (2020) by Lee Ji-yeon

Lee Ji-yeon directs a movie that shows the impact of the housing issue in Korean, by implementing a rather dramatic approach to the whole concept. In that fashion, the narrative basis of the single mom who is also homeless and has to trick her kid in order for him not to realize their situation is rather impactful. Even more so due to the finale, which can be described as brutally pragmatic. At the same time, the short does cross into melodramatic territory, despite its realistic premises, and even if Lee keeps it relatively grounded.

10. Warrior (2022) by Amanbek Azhymat (Kyrgystan)

One of the more pessimistic, but nevertheless correct observations about human existence is the prevalence of conflicts. War brings change, as Clausewitz states, and has therefore a purpose, while at the same time it comes with a huge price. In Azhymat's feature this truth is dealt through two aspects, the characters and the idea of the kind of purgatory they are in now, which also is the setting for the majority of the feature. It is a barren wasteland serving as the kind of image your might have of purgatory, while at the same time highlighting the outcome of all of the wars, an empty landscape with not people and not vegetation, with only the lost souls of fallen soldiers inhabiting the space. Azhymat's use of setting seems to hint at the absurdity of violent conflict, the toll it takes on our home and ourselves. (Rouven Linnarz)

11. Did It Hurt? (2022) by Nathan Carreon Lim (Thailand)

Nathan Carreon Lim directs a film that unfolds as a fiction/documentary hybrid, in one of the best combinations we have seen in a style that has become quite prevalent recently. The way he achieves that, by including narration from the actual person, flashbacks and flashforwards, all until the apogee of the fight all work rather well, with the pace of the story being ideal. The same applies to the change from monochrome to color, while it is easy to say that Chonborvorn Niyamosatha's cinematography is top notch. Especially the scene with the water, and the initial match are impressive to watch, as is the scene with the TV close to the end. The same quality applies to Isaac Allen's editing with the succession of the aforementioned elements being also great.

12. Murder Tongue (2022) by Ali Sohail Jaura (Pakistan)

There is something to be said about the amount of drama Jaura manages to pack into his 18-minute-short. While the first half captures the growing family drama, ignited by the son seemingly gone missing, the other half shows the sheer amount of unrest and brutality which has erupted in the streets of the city, resulting in a heart-wrenching finale in the hospital. Although Jaura is careful to focus on Abdul's family, he emphasizes how many go through similar traumatizing experiences, with aspects such as the sound design, the lighting and Mo Azmi‘s cinematography stressing the growing violence within the streets of Karachi, turning it into something close to a war zone. (Rouven Linnarz)

13. Abridged (2019) by Gaurav Puri (India)

It is impressive to watch people having set up shops under the constructions for example, as a shoe salesman highlights quite eloquently, while a number of them, seem to actually live beneath them. Schoolgirls playing with a dog, a mother combing her children's hair, a chicken jumping in front of a motorcycle, cars parking are just some of the things that happen under bridges, in a testament on how life can take place anywhere, particularly in such crowded places as Kolkata.