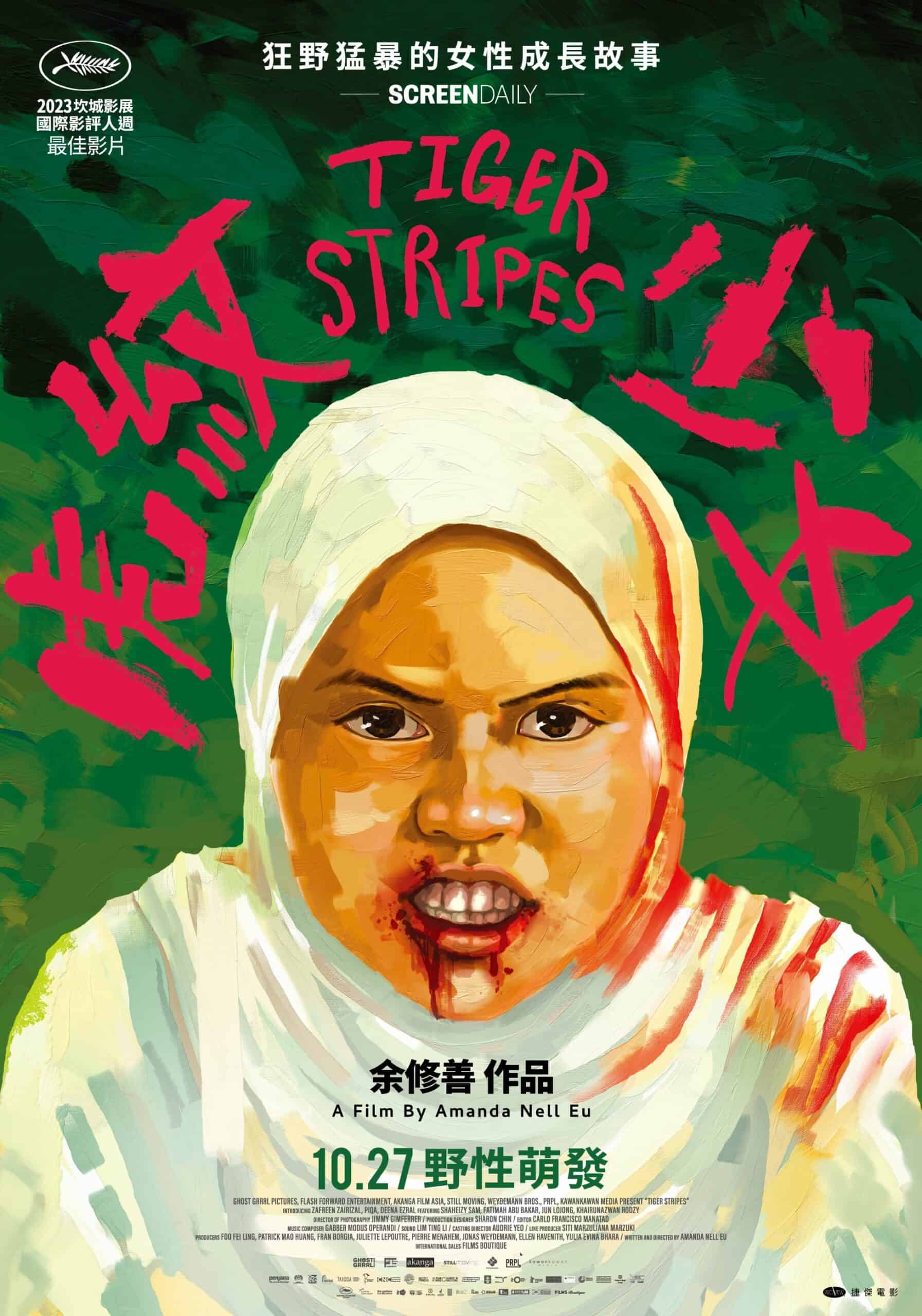

Newcomer Amanda Nell Eu's body-horror coming-of-age flick, “Tiger Stripes,” has been the hot topic of Southeast Asian horror in the last year. Eu won the Cannes Critics' Week Grand Prize, and her first feature garnered laurels since at the Asian Film Awards, Fantasia, Neuchatel, Pingyao, and more. The film had also represented Malaysia for its Best Foreign Language Film entry to the 2023 Oscars – but had to do so under intense scrutiny. Domestic theatrical release of “Tiger Stripes,” which follows Zaffan's (played by the tenacious Zafreen Zairizal) first encounter with puberty, faced strict censorship. The Malaysian release in turn removed scenes like a rambunctious TikTok dance, an explicit shot of period blood, and schoolgirls trying on a friend's bra for the first time.

Now, in the advent of “Tiger Stripes'” US premiere, we had the fortune to speak to Eu over Zoom. Over the course of the half-hour, we exchanged horoscopes (we're both Sagittariuses!), talked about the mystery of the jungle, and underscored the importance of loving your whole self.

This review has been edited and redacted for clarity. You can read our review of the film here.

How did you develop the mythos for your film?

Amanda Nell Eu: It's from my obsession with folklore and genre. Prior to “Tiger Stripes,” I made a lot of short films when I returned to Malaysia. They were always dealing with the female body and characters that were outsiders, feared, or shunned by society. These characters are oftentimes iconic female monsters or creatures in our folklore – my heroes. I wanted to have their powers. I wanted to be angry like them, and do what they did to people. (laughs)

With “Tiger Stripes,” I wanted to talk about a child who, overnight, has to carry all these expectations of being a woman in society. It's her first time learning about fear and rejection of her body, about shame and insecurity. [I also wanted to show] how she overcomes it, while playing with a lot of horror visual language from Southeast Asia.

When I first watched “Tiger Stripes,” I immediately thought of the Pontianak [a vengeful female spirit in Southeast Asian folklore, oftentimes associated with childbirth or stillborn children]. There were moments in the movie, however, that seem like borderline pregnancy – like Zaffan's nausea, her hunger cravings, and so on.

[Zaffan] is definitely an amalgamation of creatures like the Pontianak, the Were-Tiger, Orang Bunian. We shoot a lot in the jungle at night, and sometimes we would talk about things that we saw there, like a pair of red eyes looking down at us from the mangosteen tree. It's the language that we use to describe our monsters, the supernatural, that is tied to the jungle around us.

What is your personal relationship to the jungle?

I was born in Malaysia, grew up in the UK between 11 to late 20s, and then moved back here [to Malaysia]. That's why I love [the jungle], because I don't have access to it. I was working with the cinematographer, discussing how we should shoot it, and it's almost like a fantasy land. Sometimes we would light it as if it was like a set, almost artificial. So many stories, so much mystery and beauty, and so much wild, violent energy comes from the jungle. Having grown up in the city and city-like places, [the jungle] is my fantasy as well.

There are resonances to Korean folklore too, with our relationship to the mountains. My parents' place in Seoul is next to a mountain, but I don't dare walk around there at night.

It's terrifying to go in at night, especially on your own. So I get the chance to do that with movie sets. (laughs)

What did shooting in the jungle at night look like logistically for you?

Generators, of course, but I am also quite used to shooting in the jungle. I'm more comfortable shooting in the jungle than confined spaces. When we were shooting “Tiger Stripes,” we were just so much more uncomfortable in the school.

The school was one of the toughest places to shoot – it was almost like we couldn't breathe, even though we had access to the toilet, electricity, and the like. When we moved to the jungle though, it was like a literal breath of fresh air. It was a lot more fun, more free.

How did you find the school?

I always wanted to have this fairy tale look. Fairy tales always begin with, “Once upon a time, a young girl lived far, far away” – so I wanted this notion of “far, far away.” Where is “far, far away”? We don't know. Where is the town? We never find out. But the important thing is that it happened, like a fairy tale. So we kept looking and looking and looking until we found this school at the end of a village, surrounded by mountains, that was only 45 to 50 minutes away from the city.

And why depict puberty?

It's all so visceral. Everyone has felt like a monster or ostracized while they're growing up, but have also felt a lot of love from their friends and a sense of naughtiness and rebellion. These are obviously very honest and true to my experience, but I think they are very relatable to young people today.

Between Zaffan, Farah, and Mariam, who do you relate the most to?

There's a bit of me in all three of them. I wish I was as strong as Zaffan; I think I am starting to be more like her the older I get. [When I was younger], I was definitely afraid, like the other two.

Shuchi Talati told me something similar with “Girls Will Be Girls” (2024), where she mentions that she she could've been stronger, like her coming-of-age protagonist, in her own past.

One of the most beautiful reactions I heard was when someone same up to me and said they relate to Farah, the mean girl. I said, “That's very brave of you to say that.” Then they told me, “Well, we are all afraid. We are all her. How can we always be as brave and strong as Zaffan, to push through and be your full self?” And that's really the point of the story – to fight for that and your freedom to be your whole beautiful self, in spite of what other people say is “hideous” or “gross” or you should be “ashamed of.”

Speaking of shame: there really is no shame like the smell of a period, and that comes through again and again in your film.

You can't smell a film, unless you want to make it a 4D experience. (laughs) But even in development, I wanted to have that feeling of smell, through stories the characters read online and their interpersonal relationships. The film has to be sweaty and smelly, with raw body fluids.

We also feel this wetness when Zaffan floats in the water in both the beginning and the end.

Yeah. Wet fluids. Just feel the heat, feel her.

Switching gears: I noticed that you have a string of co-sponsors. How did you make your first feature work?

We started developing at the end of 2017, and we went through that typical arthouse route. We started with a bunch of labs, then film markets, and it was a step-by-step learning curve for me and my lead producer Foo Fei-Ling. Funding the film from a studio here in Malaysia was tricky. It's a risky topic, it's not a commercial-type feature, and it's also a first feature [for me]. So we had to make it through public grants and funds, ending up with eight co-producing countries.

How did the film change over time?

It's always had the same heart, this fight for freedom to be your full self. The changes just made the film a lot better. The labs helped me discover the soul of the film, and then everything after became an organic way for the film to grow. The key image on the poster has the same heart as when I first developed the film.

I've also heard that this film is censored in Malaysia.

Yeah, for the theatrical release.

How do you balance these tensions – of universal tendencies, telling a local story, and censorship – in your development?

Well, I didn't balance the censorship part. (laughs) I was in a privileged position to not have to self-censor; there are a lot of filmmakers who need to do that because they rely on the box office, or the way that the film is financed. We did the theatrical release for Oscar-qualifying reasons, and we have to deal with the censorship as a part of making film in Malaysia.

Balancing the universality and Malaysia specificity was very natural. I did a lot of research. I went to a lot of schools, spoke to a lot of women in Malaysia from different cultures. Casting allowed me to do another kind of research, to talk to young women and what they were going through. It fell into place where these themes and topics were still the same, but we were playing with the folklore.

It was comforting to watch the beginning of the film where Zaffan and her friends are hanging out and think, “Great, the kids haven't really changed.”

It's definitely a mix of my personal experience and working with the young girls and what they bring to it. The kids are still the same – they're still curious, they're still rebellious, and they're still going to hide in little corners and do things on their own and hope they'll never get found out.

Will you work on a coming-of-age film again?

I want to do more mature themes now, delving into themes of motherhood and the expectations of that — while also having fun with genre.

That's the Sagittarius way. (laughs)

That's right, I'll see what's there and go with the flow. (laughs)

“Tiger Stripes” premiered in select US theaters on June 14, 2024.