The article contains spoilers

A lot has been made about Sanjay Leela Bhansali's adaptation of Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi's epic poem “Padmavat” (1540). Even before its release, the film had been mired in controversy due to rumors regarding tampering with Rajput (an Indian community historically known for their valor and honor) history and a prominent figure, Rani Padmini, in their lore. From vandalism on set and threats to the actors and Bhansali himself by right-wing groups to the eventual delay in its release (it was supposed to release on December 1, 2017), “Padmaavat” has been through a lot of trouble (it even lost the ‘i' from its title). All of this trouble with an extremist right-wing group gave an impression that probably the film could build a counter-narrative against the glorification of ‘jauhar' (self-immolation Rajput women used to perform in order to save their honor from victorious enemies) in Rajput lore. But alas! It was too much to expect from Bhansali.

Rani Padmini (Rani Padmavati in the film) is the central character in Jayasi's poem. She is known for her matchless beauty, wisdom, and courage. Although in Bhansali's adaptation Rani Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) is bestowed with all of these traits, it is far from anything related to women empowerment.

Padmavati and Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor), the ruler of Mewar, meet during a hunting expedition gone wrong. Ratan Singh is injured by an arrow shot by Padmavati. The two soon fall in love and are married despite Ratan Singh being a married man. Due to a certain chain of events, word about Padmavati's beauty reaches Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh), the Sultan of Delhi. He is possessed by the desire to acquire Padmavati and so lays siege on Chittor (the capital of Mewar). And the contest between two men over a woman ensues.

Bhansali chooses to treat the characters more like archetypes than actual human beings. Padmavati is intelligent, beautiful and brave, with no visible flaws. She becomes the perfect trophy wife for Ratan Singh who is courageous, handsome, sophisticated and morally upright. Khilji on the other hand, contrary to historical records, has been portrayed as a brute, barbaric and treacherous conqueror. This compartmentalizing of characters into good and evil, black and white lends no depth to them and they largely remain as live mannequins in lavish clothes and jewelry, mouthing crowd-pleasing but hollow dialogues.

It is also due to the endorsement of this binary of good versus evil, Rajputs versus Khiljis that the politics of the movie, even without its glorification of jauhar, becomes unpalatable. These are the times in India when nationalist sentiments are being fanned by the right-wingers. Anyone who is opposed to the views of the right-wing, which incidentally is very vocal about its Hindu roots, is branded as an anti-national. So naturally, the depiction of a brutal ruler of Islamic origin wrecking havoc on the Hindu Rajputs in order to attain a Hindu queen is going to rouse nationalist sentiments and further the prejudices against the Muslim community. And boy, does Bhansali deliver on prejudices!

Ranveer Singh's portrayal of Khilji is one-note evil and Shahid Kapoor's the exact opposite, still one-note though. Khilji and by extension the Muslim community becomes the exact opposite of the good and the morally superior Ratan Singh and the Rajputs. What's not to hate about Khilji? He is a monster, who murders his own kin, beds other women on the day of his marriage, lusts after married women, loots and plunders, and even eats flesh like a ravenous monster. He is the exact image of a Muslim man in a Hindu fundamentalist's mind. Bhansali's choice to further this prejudice is very unbecoming of a filmmaker of his repute.

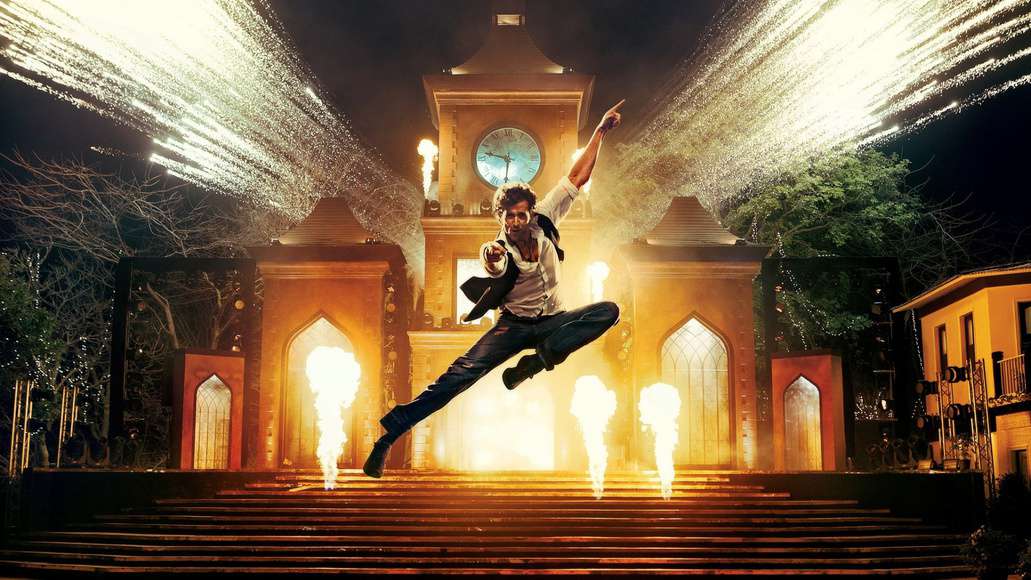

The movie is undoubtedly a visual treat, with lavish sets, gorgeous costumes, symmetrical frames, and good-looking actors who give competent performances. Ranveer Singh is the highlight among actors, comfortable in his villainous turn, although he never quite manages to turn it into pure menace. That is probably more of a writing flaw than Ranveer's performance. Deepika is good as the headstrong Padmavati, definitely better than she was in the last Bhansali movie, “Bajirao Mastani” (2015). However, Shahid Kapoor's performance, despite his superior acting chops, comes off as a little forced.

Bhansali has an eye for detail and love for grandeur when it comes to production design and costumes. Multiple teams of costume designers and Amit Roy and Subrata Chakraborty, the production designers for the film, have done an excellent job to bring Bhansali's vision to the big screen. Complimenting the rich texture and color of the sets and costumes was Sudeep Chaterjee's efficient use of dramatic lighting, wide angles, and a subdued color palette. Chaterjee, like in “Bajirao Mastani”, makes the most of wide angle to put as much detail on screen as possible. While there is always a fear that this technique may distract the audience from the actors on screen with an overload of visuals, Chaterjee does a great job by choosing to subdue the colors, so that we never get a full-blown red or green. Instead we see black and white, in their different shades, turn out to be the dominant colors, complimenting the leitmotif of good and evil throughout the film. It is only in the final scene that red becomes the dominant color, signifying the power of the women's passion before they sacrifice themselves.

Competent acting and visual appeal notwithstanding, “Padmaavat” is haunted by further problems of a weak screenplay, unnecessary although real historical characters (I am looking at you Malik Kafur, although competently played by Jim Sarbh), a boring subplot involving Alauddin's political strife for the throne of Delhi, and unnecessary and unmemorable songs. The film suffers from ordinary editing. The weak screenplay and less than interesting characters did not deserve its nearly 3-hour run time. Once the jingoism of “our honor” and “their treachery” starts, it doesn't seem to end, and therefore becomes quite repetitive. There is hardly a moment of tension in a movie that boasts two instances of siege and one escape scene. The editors could have sped the pace up of the movie to build some tension, it really required it.

However, “Padmaavat” suffers most of all because of its take on jauhar. At the beginning of the movie, an unnaturally elaborate disclaimer (thanks to violent right-wing protests) states that the movie does not intend to endorse the practice of Sati (another erstwhile evil practice involving self-immolation performed by women on account of the death of their husbands). However, it seems that for Mr. Bhansali one form of self-immolation is better than the other, for he manages to present jauhar with quite glamorous veneration. If sati was an evil practice forced upon women, jauhar was a brave and honorable death embraced by courageous women “willingly”, at least this is what the message the movie sends across. The final image of Padmavati and a throng of women sacrificing themselves at the altar of honor becomes the central theme of the movie. What could have been a defiance of the regressive patriarchal values succumbs to Bhansali's attempt to please the patriarchal majority, and in the process comes off as aggressively nationalistic, misogynist, Islamophobic, and even homophobic.

There are fleeting glimpses of redemption in the movie like Khilji and his coterie indulging themselves in a poetry recital and the agency provided to Padmavati in the second half of the movie (she plans a daring rescue of her husband thereby exposing the foolishness of his honourable decision which gets him caught). However, such moments are few and don't last long enough to leave an impression, as Khilji breaks up the recital to mock another contender to the throne; Padmavati uses her agency to commit jauhar; and Ratan Singh's foolish yapping about honour and reckless pursuit of the same finds approval because of Khilji's treachery.