The issue of bullying is one of the most significant nowadays (to say the least) in Asia, and particularly in Japan, where the statistics are truly frightening. According to The Japan Times, “The number of reported cases of bullying at Japanese schools hit a record high of over 320,000 in the 2016 academic year due partly to efforts to detect early signs, according to the education ministry. A total of 323,808 bullying cases were reported at elementary, junior high and high schools, up 43.8 percent from a year before, with the figure for elementary schools jumping 1.5 times.

The problem, however, is also at large in S. Korea, where according to The Korea Times, “More than 30 percent of students in South Korean elementary, middle and high schools are victims of bullying. The data was gathered by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs and found 32.2 percent of respondents said that they have experienced violence at school. By age groups, 38.6 percent of respondents between 9 and 11 years of age said they have been victims of assaults, while only 29.7 percent of respondents between 12 and 17 said they have been abused. Not all the respondents were victims. More than 20 percent of respondents answered that they have been offenders.”

Expectantly, a number of directors from those two countries decided to tackle the issue, which resulted in a number of quite impressive productions, with a number of them bordering (and occasionally reaching) on being masterpieces. Here are 10 great samples, including a film from Taiwan of at least equal quality.

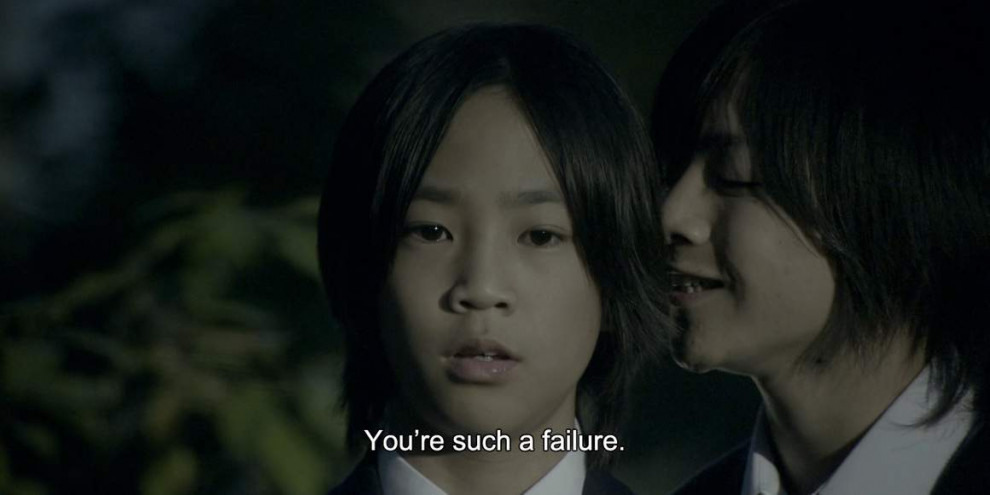

1. Confessions (Tetsuya Nakashima, 2010, Japan)

Based on the novel by Kanae Minato, “Confessions” deals with the tragic story of Yuko Moriguchi, a junior high school teacher. One morning in the classroom, after distributing milk to her students, she proceeds to inform them that this is her last day at school.

Two facts regarding this teacher were common knowledge, up to that point. Her husband is HIV positive and her daughter, who attended kindergarten, was drowned in the school's swimming pool by accident. However, she discloses that her death was not an accident, but a murder, and the two perpetrators are presently in the classroom. She does not name them; nevertheless, she presents enough evidence for the rest of the class to not have doubts regarding the wrongdoers. Furthermore, she states that she has inserted blood from her husband inside the milk boxes of those two students, who have already consumed it.

Tetsuya Nakashima depicts the film mainly through flashbacks resulting from the confessions of the protagonists. Furthermore, he presents a number of social issues including sexuality, death and bullying, as well as the relationships between parents and children, between teachers and students, and between parents and teachers.

Another characteristic of the film is that the majority of the protagonists are drowning in their need for revenge, a notion that causes to the film's audience to not be able to sympathize with any of them, despite the fact that they all are victims.

Equally impressive is the fact that he manages to provide humor, however cruel and dark, in a cold, psychological thriller.

Buy This Title

2. Liverleaf (Eisuke Naito, 2019, Japan)

“Liverleaf” is a Japanese teen drama about bullying, based on the manga series “Misumisou” by Rensuke Oshikiri.

A newly admitted transfer student, Haruka, gets bullied at her new school. Her only friend is another transfer student, Mitsuru. One day they meet up to go and take photos of the snow-covered village. On their way back, Haruka discovers that her house is on fire, with tragic consequences for her whole family. In the aftermath, she decides to exact revenge in the most violent way.

Eisuke Naito takes the concept of “bullying the bully” to its most extreme, as eventually, vengeful violence takes over the narrative in the most shocking fashion, while the teen drama elements seem to move the narrative even further to this particular direction.

Through this extremity, Naito also seems to put the blame to the lack of guidance these youths experience, both from their parents and their teachers, both of which shine through their absence.

Hidetoshi Shinomiya's cinematography is one of the biggest traits of the film, with the scenes in the snow being the ones that stand out, being both meaningful and quite artful.

3. Han Gong-ju (Lee Su-jin, 2013, S. Korea)

The films is based a truly horrid actual event, where 41 high school students repeatedly raped five girls over the course of 11 months. The script stays quite close to the actual facts, focusing, though, on the titular girl. Initially we watch Gong-ju after the arrest of the perpetrators, having transferred to another school and living with the family of an ex-professor of hers along with his mother, an owner of a convenience store. Her parents have abandoned her, with her mother in a new romantic relationship and her alcoholic father still living in the village where she was born.

The girl tries to keep a low profile and even manages to make her host like her, despite her initial objections about her living there. In her free time, Gong-ju learns how to swim in the local pool, where she eventually meets another girl, Eun-hee, who actually imposes her friendship onto her, making her open up a little. Even this lesser happiness, though, does not last for long.

Lee Su-jin in his debut directs and pens a powerful, touching and occasionally brutally realistic film. His strongest point is the depiction of the protagonist, with the camera following her from a very close distance, drawing the spectator deeper and deeper in her world.

The film is definitely dramatic, but Lee manages to retain a sense of measure for the duration of it, avoiding the reef of the melodrama while retaining a sensitive approach toward a very difficult subject, with most of the events being implied rather than depicted. The use of flashbacks stresses this approach, despite the fact that their use in the beginning can be somewhat disorienting, although this is remedied as the story progresses.

The film is not completely void of shocking scenes, but the majority of them are presented toward the end, in a tactic that heightens the agony, both for the result and the roots of the girl's issues. His message is quite eloquent: the cycle of violence never closes.

Buy This Title

4. All About Lily Chou Chou (Shunji Iwai, 2001, Japan)

The story revolves around two boys, Yuichi and Hoshino, starting from the first term of junior high school and finishing after the second, although in a non-linear narration, that begins midway, goes back to the beginning and then to the present again. The two of them become friends when they both join the kendo club, with Hoshino proving kind and very communicative, in contrast to the timid, introvert Yuichi. A summer trip to Okinawa after the end of the first term, and a near-death experience Hoshino endures, changes him immensely. Starting next term, he becomes a harsh manipulator of everyone around him, bullying Yuichi constantly and harshly, and even prostituting a classmate of theirs, Shiori, after blackmailing her. Shiori seems to have feelings for Yuichi, but he is interested more in Yoko, another alienated student, who also falls victim to Hoshino and his gang in the harshest way. Through all these torturing experiences, Yuichi's only solace is pop idol Lily Chou Chou's music and a fan site dedicated to her he is administrator of.

Iwai directs and writes a truly shocking film regarding school alienation and the terrifying cruelty of teenagers that leads to harsh cases of bullying. The diptych of Yuichi and Hoshino represents the victims and the perpetrators of both the aforementioned concepts, with the narrative focusing on the impact their (in)actions have both on them and those around them. The fact that both are unable to escape the circle of violence, some additional revealing regarding Hoshino's radical change, and the truly shuttering finale stress the fact that in these concepts, everybody is a loser. Furthermore, Iwai seems to blame the parents for their torments, with them either being completely ignorant to what is happening in their children's lives or completely unable to handle any issue that arises, with the scene in the principal's office between Yuichi and his mother being the most evident sample.

In the 146 minutes of the movie, Iwai also deals with a plethora of other issues of contemporary Japanese society, such as Jk business (compensated dating between older men and adolescent girls), rape, social media (even in their early form of chat rooms) and the concept of idols.

However, his presentation of all the aforementioned is implemented in an abstract way, with many “artistic” intervals in-between the progress of the story, in a tactic that makes the film more beautiful, particularly through the combination of image and the almost constant use of classic and electronic pop, but in essence strips a great story from the impact it could have with a more “traditional” approach. This style is chiefly represented in the concept of Lily Chou Chou, a pop idol who never really appears in the film, although her impact is evident by the protagonists' conduct, particularly regarding their neediness for something to hang on due to their alienation. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

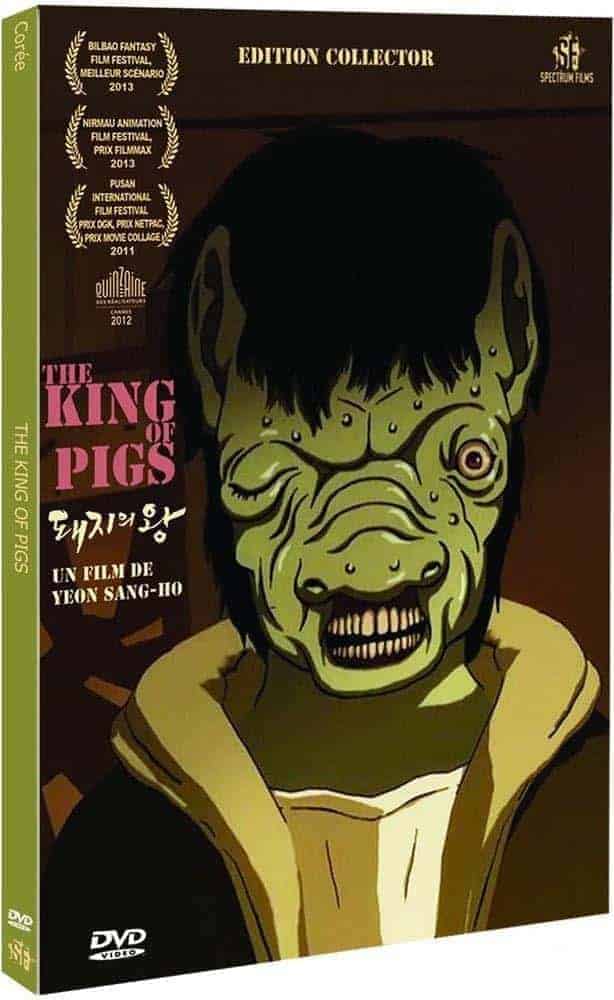

5. The King of Pigs (Yeon Sang-ho, 2011, S. Korea)

The story revolves around two former classmates, businessman Kyung-min and writer Jong-suk. In the present, both of their lives are in shambles. Jong-suk is forced to do menial work, such as ghostwriting, and has to face a rather obnoxious boss who keeps demeaning him. His frustration erupts violently toward his wife, who, despite his behaviour, seems to love him very much.

Jong-suk is in an even worse position since his business has gone bankrupt, and he has just killed his wife. After the murder, he calls Jong-suk, who he had not seen in 15 years, and the two of them go for a drink and start reminiscing about the past. Through flashbacks, the movie reveals the situations they faced in school, in a story of bullying, drama and constant violence that also involves a third member, Kim Chul, the “King of Pigs.”

Yeon Sang-ho (who is responsible for the direction, script, editing, character design and key animation, among others) uses the school environment to make a very harsh remark about a number of aspects of Korean society. The racism in school, where all students are classified according to the wealth of their families, who even give money to the school for their children to receive special treatment, is a main point of focus, as it highlights the concept of class warfare.

The privileged are known as “dogs”, while the ones at the bottom, as the three protagonists, are known as “pigs”. The subsequent bullying that ensues from top to bottom is another key element of the film, as is the social injustice involved, with the teachers pretending to not realize what is going on, and always turning on the “pigs”.

Kim Chul functions as a ray of hope in this hellish setting in which Kyung-min and Jong-suk live, but this is not a light film with a happy-ending, and Kim Chul's way to face the bullies is to become worse than them, by being even more violent than they are. The disgrace and constant bullying even makes the two others to begin acting accordingly, although their true nature eventually takes over.

Lastly, a minor comment regarding consumerism is presented through Jong-suk's sister.

I heard someone say recently that there is nothing more terrifying than a group of teenage boys. Simply because boys at that age are so full of pride and surging testosterone and all want to outdo each other and impress each other any way they can, and that can so quickly and easily lead to anti-social behaviour and violence that gets way out of hand.

I brushed up against it a little when I was a teenage but I was smart enough to pull back and avoid those circumstances. But seeing how fast potentially fatal situations can arise during the course of general socialising among boys and young men certainly makes me wary of groups of them to this day.