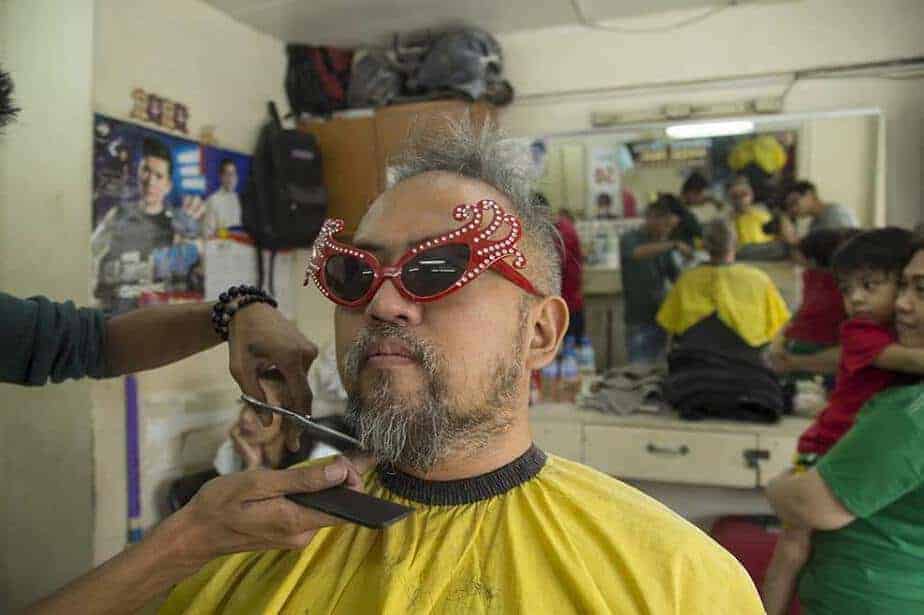

Khavn De La Cruz is a multi-awarded and internationally renowned filmmaker, composer, and writer. He has forty-six features and more than a hundred short films under his belt. Once the proprietor of the late 90s go-to place for local artists Oracafe, Khavn has been called the father of Philippine digital filmmaking. He has served as jury member at the Berlinale, Clermont-Ferrand , CPH:DOX, Jeonju, Jihlava, & Dok Leipzig film festivals and is the festival director of .MOV International Film, Music, & Literature Festival, the first digital film festival in the Philippines. Khavn has also judged in the Palanca National Literary Awards (the Philippine equivalent of the Pulitzer) and has won for himself in poetry and fiction.

He has been selected thrice in the National Writers Workshop and was invited to a writing residency in Ventspils International Writers House, Latvia. Khavn has received the Dean's Award for Literature from his alma mater, the Ateneo De Manila University, where he also has lectured about the creative process. Five of his books have been published, which includes an anthology of Philippine poetry, two poetry collections, a non-fiction compendium on new Philippine cinema, and Ultraviolins, hailed as the first postmodern book of stories in Filipino. Khavn is also an award-winning songwriter and has performed his original compositions, either as a solo pianist or with one of his three bands Fando & Lis, The Brockas, and Vigo in places such as Thessaloniki, Austin, and Brisbane. He is the president of Kamias Road, an independent film, music, and publishing company.

We speak with him about his career, his unique style in filmmaking, music, the police, Metro Manila and many other topics

You have shot 51 features and 115 short films since 1994. Furthermore, you work as a composer, songwriter, and writer. Where do you find the inspiration, the will and the time? Do you ever feel tired?

I am always thinking my output/work defines me. That I don't exist, that I'm not being if I don't make anything. Being tired is part of the process. It's wrong to believe one does not get tired when one is passionate.That's not true. Even machines break down .If you're tired, just take a break. Go for a walk. Dance. Re-energize. Do something else. Then go back to what was left unfinished.

I'm always tired, and I always think I'm not doing enough. But at the end of the day, we just do what we can: stretch, like rubber.

What are your influences as a filmmaker, and in general, where do you draw inspiration from? What kind of films do you like to watch?

Everything that I'm surrounded by: the good & the bad & the ugly, cookbooks, receipts, order slips for construction materials. I also learn a lot from bad movies, bad being relative. the “badder” they are, the more I enjoy them.

For inspiration, I look to the surrealists, from pre to post, and outsider music from sun ra to moondog. Tthen there are the theaters of cruelty, the absurd, the oppressed, and this book: “Barbaric, Vast, & Wild”.

Filipino art is not so well known, particularly in the western world, but you have managed to transcend the borders of your country, gaining international recognition. How difficult was that and how did you achieve it?

I just did my thing, in complete obscurity at first. I wrote poetry and fiction, I composed songs, instrumental music, I made shorts, features. You do what you have to do. Then one by one, slowly, almost inch by inch, a door opens. Someone likes what you do, you get a pat here, a nod there. You come across the like-minded, people you can form an alliance of tastes with.

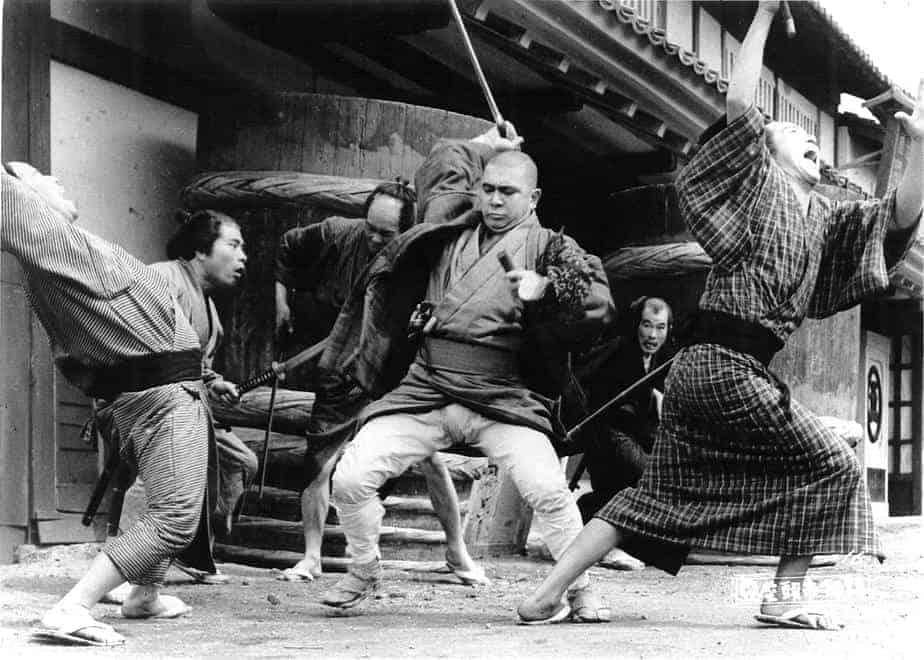

Your films, such as “Alipato” and “Ruined Heart” implement a kind of chaotic approach to their narration, much like a collage of ideas that come together through the editing. Why have you chosen this method, and how do you manage to present your stories through this chaos? How do the editors of the films feel about it? (This last question is kind of a joke)

“Why” is a big word. “How: is a long word. As cliche as this may sound, I didn't choose this method, the method chose me. Maybe I just have a chaotic mind. My brain interprets the world as a collage. I like the whole strategy of cut and paste, dealing with fragments, playing with incomplete puzzle pieces. Incidentally, collage happens to be the root word of my favorite word bricolage, the study of broccoli.

In the beginning, Ι edited my films. But now, I prefer to collaborate. For more chaos. Ideally, the editor hasn't read the screenplay, if there is one to begin with. Most of the time, there isn't. I also ban the editor from the pre-production and the shoot itsel,f so he has a fresh take on things. The virgin kino-eye, in a manner of speaking. The exquisite corpse of filmmaking. When my editor sees the footage for the first time, Itell him to forget chronology and assemble the scenes the way they appeal to him. Editing (along with sound design and coloring) is the last stage of film writing. some editors like the challenge—that they're not treated like typewriters, computers; that they're collaborators in the truest sense. Some editors can't take that. They explode.

How did the idea with the tomb stones in “Alipato” came about?

I needed a punctuation mark and sinceI've always been fascinated by tombstones—the design, and the word written on them, I used them as punctuation. But think about it, a tombstone IS a punctuation. Your whole life in one short sentence. The tombstones used in the film are actual tombstones from the Manila North Cemetery, where my grandparents and other relatives are buried. That's also where we shot the last part of “Ruined Heart”.

“Alipato” seems to make a comment regarding the conditions of the slums in Metro Manila. Is this really the condition there, particularly regarding the children?

Comments are for obituarists. Metro Manila is very big, this is just one of its many pockets of life.

“Αlipato” is shot in real locations, casting real people (non-actors) from the slums (along with a few professional actors). Although it's fictionally set in the near-future, it's at the same time very real. Αs real as it gets. Τhe ruined heart of Μondomanila.

Day-old chick, the three year old boy who smokes, is the real deal. I didn't cast him because he smokes. I discovered it later during one of the breaks. His mother was letting him smoke to get rid of hunger.

“Alipato” also features a number of images that could be characterized as very extreme, from children that roam the streets half naked, carrying guns, smoking cigarettes, beating and killing people, to a number of extreme sex scenes involving an old lady and a pregnant woman. Why did you choose to use such images in your film?

Some of these things happen in real life so the film is partly a documentary. Some are urban legends, fantasies, myths, hallucinations. Filmmaking is not a 100% conscious act. Most of the time, you don't know what you're doing or why you're doing it. It's a subconscious riot. It's dreaming with the camera on, nightmares and all.

The slums have been tackled since the 50s, post-war. By now, the audience has been desensitized by poverty. They even see it now as pornographic. By using extremist tactics, one hopes to make the blind see.

The concept of extreme, like energy, is relative. images are not chosen like whores behind windows. They have feelings too, though these are much simpler than Barthes and Berger presumed.

Is the fact that the policemen frequent a bar in a pigsty a clear comment on the police in general? What is your opinion of the way police functions in the Philippines?

Let's not insult pigs—I like them a lot. But yes, the non-pigsty-wallowing police is the exception rather than the rule. The police is the corrupt muscle of politicians and the ruling class. This is the subject of my next film, “Bamboo Dogs”.

Music seems to play a very important part in your films. Can you elaborate on that? How do you choose the tracks and in general, what is the procedure you use for the music in your films?

Ss long as they still haven't perfected 4D and smell-o-rama, cinema is still sight and sound. The percentage/ratio is your call as a filmmaker. 50:50, 60:40, 100:0, etc.

Sound can also be without music, just silence or ambient sound. Or you can also phrase it like this: music can also be silence or ambient sound or noise.

But it really depends on the film. Sometimes Ι write the songs before shooting the film. Sometimes it's an afterthought. the music diet can consist of everything: recorded, live, vinyl, tape, digital, famous, obscure, local, foreign, past, present. But I welcome working on the sound design of each new film. I get to see with my ears.

Lastly, the inevitable question. What are your plans for the future?

These are all that I'm trying to do at the moment:

– finish my latest film “Bamboo Dogs” (it is finished)

– pre-production of my next film “Gugu”

– release the albums I recorded last year

– write new music

– add more chapters to my bildungsroman novel

– prepare for my installation “Happyland” in Oberhausen this May

Every monday, I do Chopin etudes and work on Ravel's miroirs. To keep my fingers limber. There is so much to read, watch, listen to.I'm always trying to catch up with the future—shoot it or write it as it happens. The future is dead, and so are we, pipapote, balulila, yadadada, that's Elmo's world!