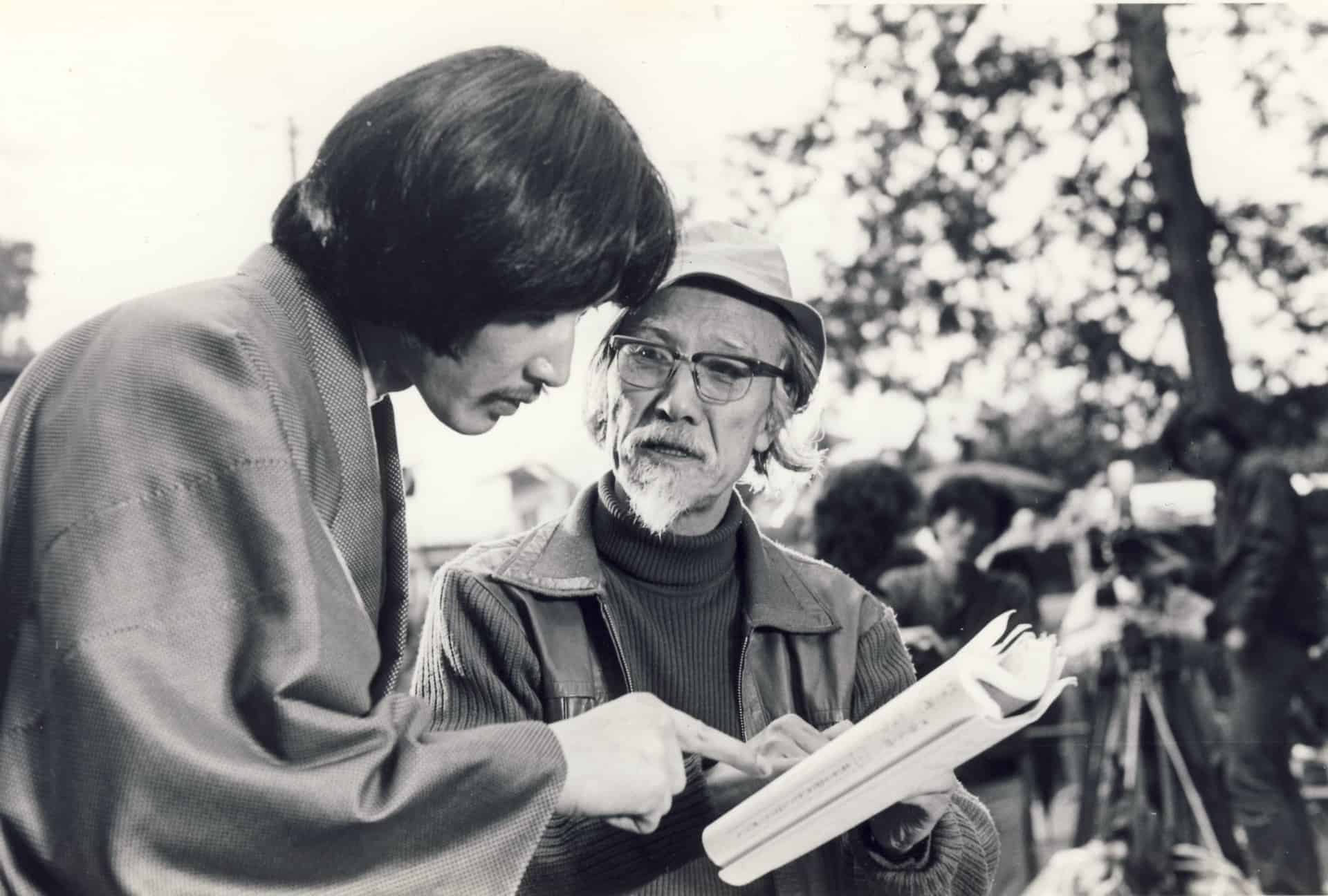

There are some films that are very difficult to review, because their importance outshines their level of quality. Kaori Sakagami, who has previously made two films about the US penal system and spent six years trying to obtain permission to shoot inside a Japanese prison, presents a documentary that is just that: very important.

“Prison Circle” is screening at Nippon Connection 2020

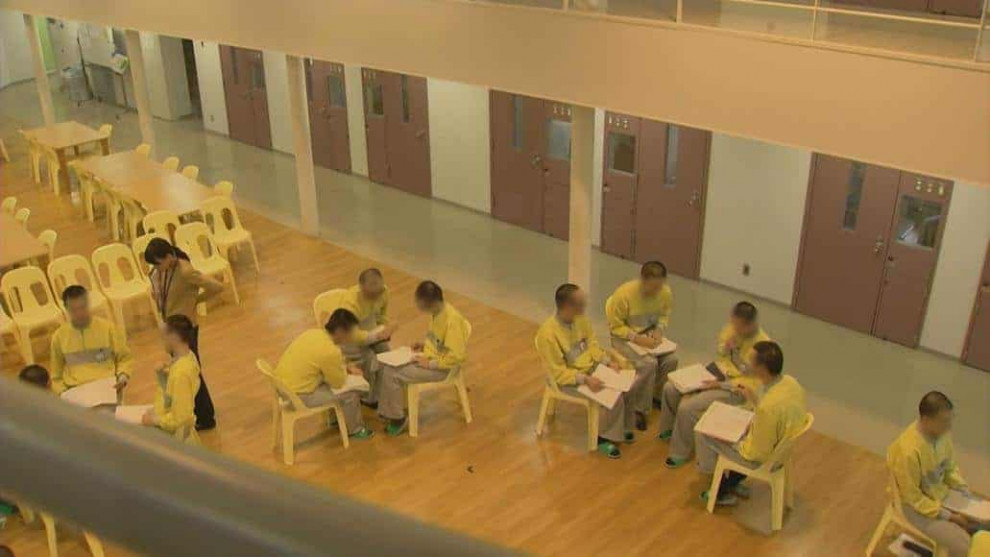

The prison that eventually gave her permission is the Shimane Asahi Rehabilitation Program Center, a facility that fosters mostly first-time offenders, and is run by a collaboration of the state with private companies. The unique aspect of the prison however, is the Therapeutic Circle (TC) program, where a group of inmates fulfilling specific criteria (a sentence of at least six months, no mental issues) participate in sessions that focus on mutual-self treatment to support each other. At the same time, the program asks them to confront themselves, their past, and the reasons that led them to crime, in an effort that focuses on true rehabilitation that actually continues after they are released.

“Although the method has been used in prisons in the United States since the 1960s, it was only introduced in Japan a decade ago. Interestingly enough, the inspiration came from Sakagami's 2004 film “Lifers: Reaching for Life Beyond the Walls.” (source: Japan Times).

In her two of years of shooting inside Shimane Asahi, Sakagami followed four inmates in their twenties, whose words, despite the restrictions imposed from the prison authorities (their face should not be depicted and any kind of interaction was restricted to specific interview times), manage to highlight the reasons that made them end up in prison and, through that, themselves as individuals, the Japanese correctional system, and most of all, TC.

In that regard, and particularly considering the way prisons are in the West, it is a wonder to watch how disciplined the inmates are, as their schedule and program are timed to the minute, their appearance is identical (same clothes and shaved heads) and they have to ask for permission for any kind of action they want to partake in. Not to mention the robot-like food carriers that bring them their meals.

Regarding TC, it is remarkable to watch how well it works, at least inside the prison, through a procedure that succeeds in making people who do not seem to have even consider of talking about themselves, revealing the deepest aspects of their character as sincerely as possible, to other inmates and the people running TC. As the interviews and the footage of the program in action progress, one factor becomes the most obvious one, that all of them had family issues, ranging from neglect to domestic violence and molestation. Through their stories, Sakagami seems to give an eloquent answer to the question of if one is born a criminal or if he becomes one.

At the same time, the honesty and openness with which they talk about themselves and their struggles, are as shocking as their stories themselves, in an element that induces the documentary with a rather dramatic essence.

Lastly, through the presentation of participants of the program after their release, Sakagami also shows that TC does not always work, although her positive opinion about it permeates the whole film.

Any kind of dramatization does not usually work well in documentaries, but in this case, the various animations that present the life of prisoners are quite well-placed and presented, and provide a much needed relief from the overwhelming plethora of dialogues and monologues, which seems to be the major issue with the film, since, at two hours, becomes somewhat monotonous and tiresome. The blurry heads actually give a sense of eeriness to the whole setting of the prison, but also do not help in that regard, since it is difficult for the viewer to separate the prisoners from each other. On the other hand, the repeated focus of Yukio Minami and Sakagami's camera on the hands of the inmates works quite well, occasionally filling the gap created by the lack of faces.

“Prison Circle”, as a film, has some significant faults, mostly revolving around the monotony and the overwhelming duration (120 minutes), but the research, the effort, and the significance of the topic deem the aforementioned insignificant and the only words Kaori Sakagami deserves are these two: “well done!”.