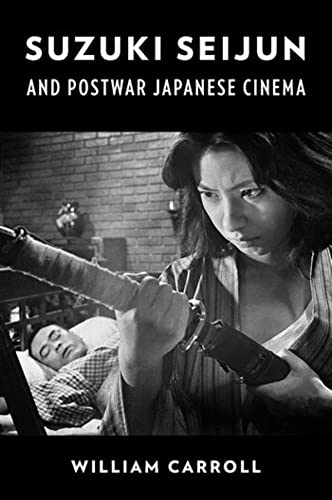

The more people get better acquainted with the Japanese language, and the more they study cinema based on local texts from the past, the more some of the preconceptions of the previous years are discarded. That Ozu is the most “genuine” Japanese filmmaker was probably the first one, but the dispelling has been continuing. William Carroll, in his book about Seijun Suzuki, also moves towards the same rethinking direction, starting with the “theorem” of “I make films that make no sense and no money” that has been defying Suzuki for decades.

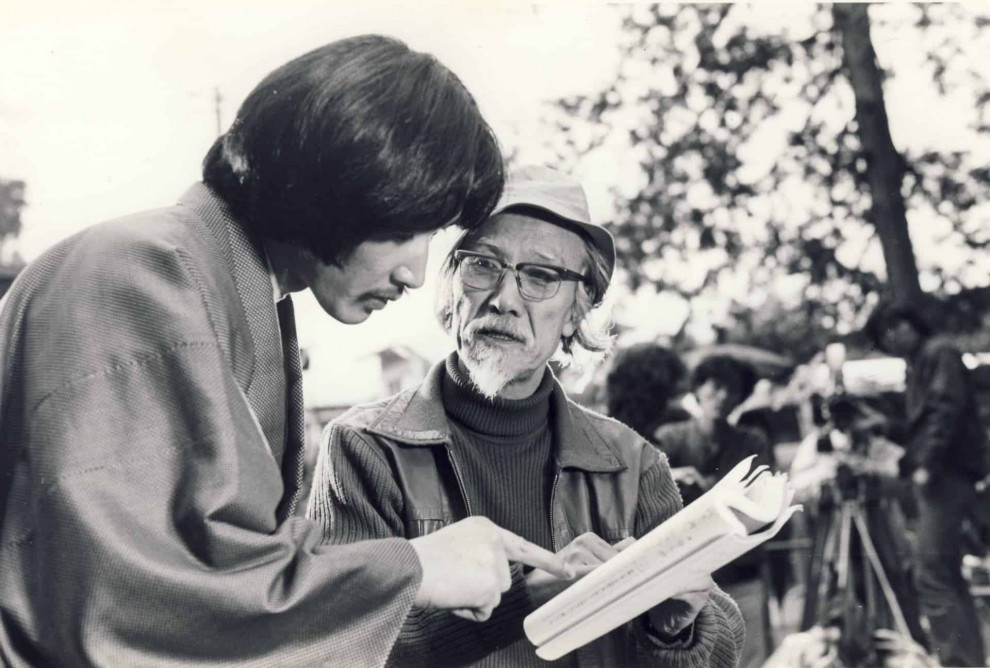

Carroll does not stop there though, essentially presenting the first complete account of Suzuki as a filmmaker, which, inevitably, also deals with the history of Nikkatsu and of Japanese cinema in general. As such, the book begins with his biography and his first steps as a filmmaker, as much as the beginning of a wider attention turning towards his work. In the first pages of the book, the focus lies on three points: the question of if Suzuki was a cinephile filmmaker (which apolitical cinephiles during the 60s suggested) or a leftist filmmaker (which the New Left suggested), with the analysis of the two “factions” being as interesting as the question. The importance art designer Takeo Kimura had in his career is the second, while the third, and one of the most significant events of both his life and of Japanese cinema is his unceremonious firing from Nikkatsu, which soon came to be known as “The Seijun Suzuki Incident” due to the intense aftermath it caused and particularly the protests that followed.

The next chapters focus on the analysis of the cinematic setting of the 60s and 70s and the place of Suzuki within it, with some of the most interesting elements being the historical info to explain the writings of the critics and scholars about Suzuki, the importance of the New Left, the connection of cinema and politics and the analysis of the term cinephile. The influence of Cahiers du Cinema, the term ‘Omoshirosa' and the cultivation of audience interest, and a “lesson” on how to review films follow next while Nikkatsu and Suzuki's transition from Nikkatsu Action to Ninkyo films emerges as another of the most interesting chapters of the book.

Read Also

The way Carroll intersperses Suzuki's biography throughout the historical events that shaped the industry is one of the best traits of his writing here, while his ending comments can only be described as eye-opening. The fact that at least half of what we knew about Suzuki is wrong and that the examination of his work can be described as trying to define an unidentifiable style are testaments to this fact.

The last part of the book moves into more analytical paths, with Carroll examining the use of space, the importance of color, the editing, the meaning of the term Seijunesque and the concept of the film within a film, among a number of others, while also including much filmmaking theory from a number of authors.

In general, there is a flow in the book that makes it easy to read even if the comments are not exactly simple, with the exception of the aforementioned last chapters, which move into a much more complicated, more academic path, including extensive terminology. The “issue” with the notes in the back exists in one more book about cinema, while the way the names are implemented, with the surname first, as exhibited in the title, can be annoying considering this form is essentially archaic, particularly in Western writing.

On the other hand the research Carroll did and the conclusions he reached make this book a necessary read for all fans of Suzuki and of Japanese cinema in general, while the complete production history of all his films, including never-before-discussed information on his unfinished film projects make “Suzuki Seijun and Postwar Japanese Cinema” a must for every Asian cinema library.