On March 20th, 1995 Atsushi Sakahara was one of over 6,000 people injured in the attack on the Tokyo metro by the Aum Shinrikyo cult, which still operates and recruits today. In his debut film, the documentary ME AND THE CULT LEADER, Sakahara embarks on a journey with the cult's executive, Hiroshi Araki, to record the parallel experiences of a victim and perpetrator. After being injured in the attack, Sakahara, who produced the 2001 Short Film Palme d'Or winning BEAN CAKE, directed by David Greenspan, suffered lifelong damage and post-traumatic stress disorder, and managed his recovery in a number of ways. He is a writer and host of the podcast Before After Aum, which focuses on the historical and social context of the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo. He currently resides in Kyoto and is working on a collection of stories and new film projects. Sakahara has been a vocal spokesperson for the attacks and process of recovery. He has spoken at the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan and been widely interviewed on his experience by the media in Japan and internationally.

We speak with him about his experience following the Sarin attack, his opinion of Araki and the results of the trip he took with him, current state of Aum/Aleph and many other topics.

Can you give us some more details about how you experienced the Sarin attack and what the consequences were afterwards for you?

It was one of the ordinary days of spring in Tokyo. I hopped onto a subway car and Sarin gas was there. I miraculously survived.

The post effect for me is called “delayed active”. It became worse later, and in 2012 and 2013, a Buddhist monk at No.1 temple of Henro pilgrimage hired me to do a shooting trip of Henro, for four seasons, in a year. But in the spring of 2014, in the airplane on my way to Tokyo, I lost consciousness and realized I experienced a spine compression fracture. Nobody knows why it happened.

I had a chance to meet Dr. Anthony Tu, the best toxic weapon expert in the world, in 2015, when he gave a lecture at Kyoto University and I asked about the post effect. He told me there is no post effect. But in 2018, in the book on an executed Aum executive, he introduced a scientific article about post effects, from a medical journal, which stays there are many people who still suffer from post effect. Dr. Tu probably kindly checked the fact after I saw him. I appreciate his kindness and sincerity.

A special law for a care program to sarin gas attacks victims unanimously passed in diet and became effective on December 2018. I don't believe the program was based on an accurate understanding of the post-effects. I think everyone would agree that the program is half cooked. Someone has to do something about it.

When the death penalty took place in 2018 for Asahara and the rest of the members, did you feel some kind of vindication?

I remember my ex-mother-in-law told me that it is premature to write my experience in the subway gas attack, because even Asahara was not executed. For this quite personal reason, I felt the world got lighter when I heard the news on Asahara's execution. For some people, especially (once) mind- controlled people, he needed to be executed. But I am not a supporter of death penalty since I know people make mistakes quite often and we could execute innocent people. I personally feel unfortunate about the rest of the executed people.

Do you have any information regarding who the leader of Aleph is now?

I think it is run by an executive committee made of about 20 members. Hiroshi Araki is the key person in administrative work. That's all I know.

How did you manage to shoot a film with an Aum member and why do you think him and the organization accepted?

Convincing Araki and Aleph is just a part of convincing the whole Japanese system. I spent a year convincing Araki and Aleph. I didn't hide anything. Early on, I told Araki that I would probably become hard on him once I start shooting but I will try to be fair. That was the key.

I am a victim, not a journalist. I was not knowledgeable about Aum and what they did. After going through the attack , I became quite skeptical, even about my own experience in the attack with a mindset, like “Maybe I am imagining my experience”. This gave me the ultimate open-mindness toward them.

I was a victim-observer in the jury trial of the last fugitive, Katsuya Takahasi, January 16th to April 30th, 2015. I shot the principal photography from March 7th to March 20th of 2015, skipping some trials. The jury trial was a great learning experience. It was so painful for me and I fell asleep often because of my psychological reactions and self-defense mechanism. I did not see Asahara in this trial but saw some people on death row and listened to their voices. Many incidents were explained very well so that laypersons could understand well. This changed me. I became tougher on Araki with full detailed knowledge. I needed to argue with the public prosecutor very fiercely to observe the trial. That was a worthwhile effort.

Maybe they had a hope, that I would tell a good story for them. Maybe they or Araki wanted to help me as a gesture of paying something back to me. But I think Araki wanted to see what would happen in his “fate”, knowing my background with many coincidences.

Sitting in the trial was suggested by a journalist whom I met during pre-production.

Why did you decide to shoot such a film though?

This film also has a Japanese title but it is only a local title. The original title is the English one. I decided to have English title as the original one because I need to share this film with the rest of the world. Now terrorism and hate are everywhere. The deep roots for these are the same as the cult, in the sense that they fall into “stop thinking” ,” lost freedom of mind “, and “seeing the world objectively”. The terror they enact and the trauma that follows is not different from what I experienced, in principle. It is good there was a person I could ask these questions to; most people cannot call up the Al Qaeda, or other terrorism groups and ask them why did you destroy my life?

During the film, you challenge Araki's decisions to leave his family, to join Aum and to continue being a member, and in essence, the whole philosophy of Aum and the reasons that led them to the attack. Araki does not have answers to your logic and questions, but never actually admits either his leader's or his own fault. Why do you think that is? Why does he insist although it becomes obvious even to him that he is in the wrong?

He is quiet but he is quite an arrogant person. The cult protected his arrogance and nurtured it. The arrogance came from his fragile and weak self. That came from the fact that he doesn't love himself. He needs to learn how to accept himself without any condition. The cult provided all of many reasons why he is better than the rest of humans on the earth. That is one of the mechanisms they have.

In general, after your trip with Araki, how would you describe him as a person?

A weak person who doesn't know how he can love himself. A very poor, unfortunate man.

Essentially from the beginning, you seem to bully Araki, who responds in timid fashion. At one point, you even both acknowledge the fact, correct? Why did you choose this approach and why do you think he reacted the way he did? I understand that the reason for your actions may be anger, but do you think he actually feels some kind of remorse, even if he does not admit it clearly?

Yes. We both acknowledged my approach very early on in filming. I was not angry. I had a hope and an expectation of him. So I didn't not give up on him. He sensed it and responded to it.

I challenged him intellectually as his classmate at Kyoto University, which is the most prolific Nobel Prize winner producer in Japan. I don't think he feels remorse. He is broken. He has probably been installed a self-restoration process in his mind by the cult. It is very sad, very very sad.

How difficult was the scene with your parents? Both for you and them and Araki?

Speaking of my parents, firstly, I would like to thank them, especially my deceased father, who died in 2019. He must have wanted to see his son's virtually first work released so badly, but he let me work uncompromisingly. He knew he would be gone soon.

It took an hour to have Araki to make an apology statement, with a very strange logic. He did it at the very last minute. We only had an hour there. I personally didn't need it and neither did my parents. I thought I could leave the tea house without having him apologize. I had the option but I didn't take it. I thought that would be very bad for Araki and his family. So I did it with my best intentions.

Why do you think he agreed to leave flowers at the victim's memorial and address the press?

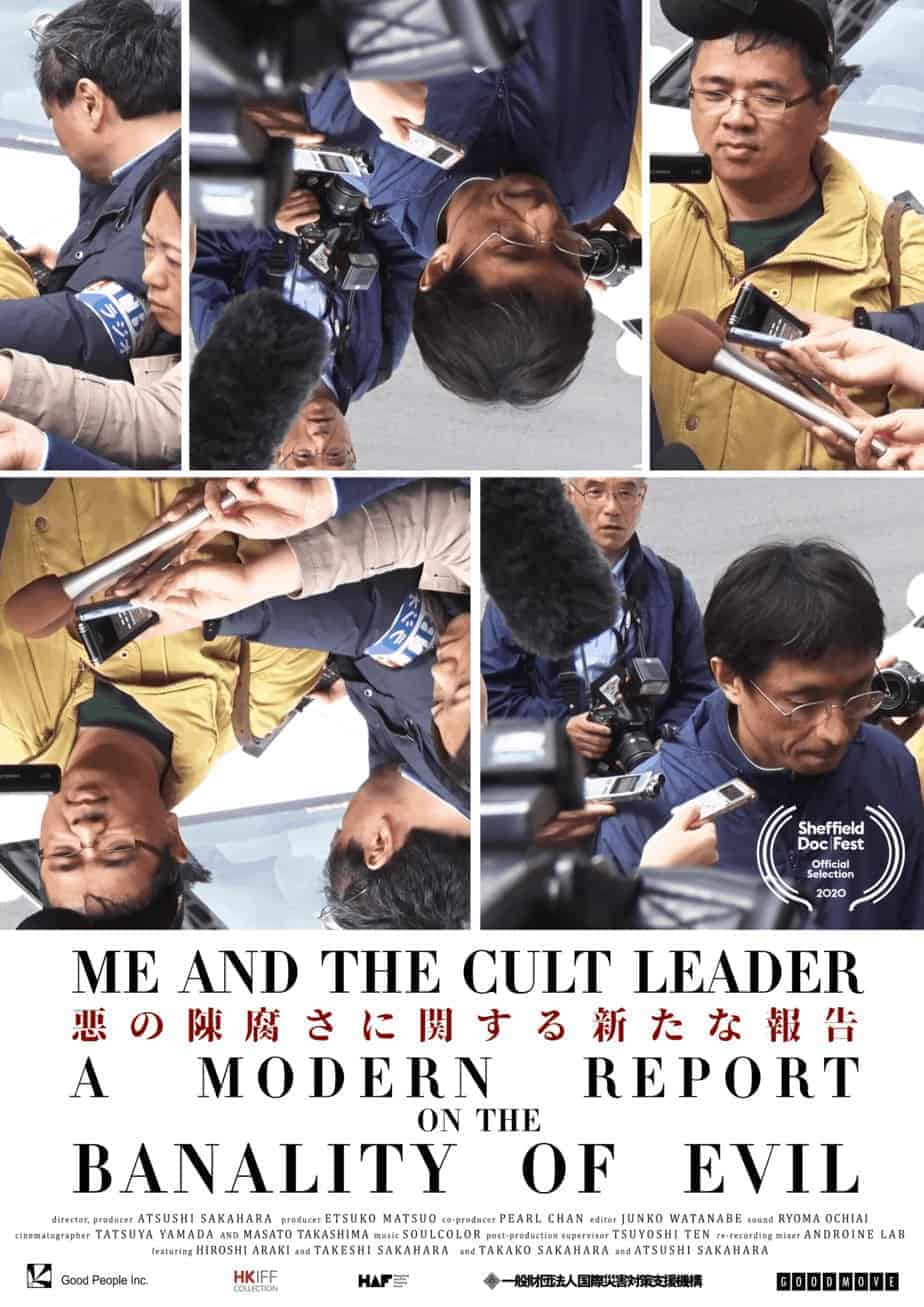

Actually, Araki goes there by himself every year in the very early morning to avoid attention. I asked him to go there with me in a regular hour. I told him that I would protect him if a media scram took place. I had hoped he would apologize to society there but it didn't happen.

How much time did you spend shooting the film and how much time did you spend editing?

I shot from March 7th until March 20th in 2015. I spent five years editing.

Did the film provide any kind of catharsis for you after you completed it? Do you still communicate with Araki? Do you think you can ever become friends with him?

I can now move on. In that sense that was my catharsis.

I try to communicate with him, but he never responds. Sometimes I was angry out of disappointment, not hate, toward him after shooting. I saw him on Christmas Eve of 2018 at a human rights gathering, run by liberal attorneys in Kyoto. I was his friend during pre-production and shooting. And I am still his friend, I hope. I don't know how to hate people. I probably lost it in the gas attack.

Can you give us some details about your future projects?

I have three projects.

I started asking “Do I really know them?” to myself when I started thinking about my autobiographical film. The question evolved into this doc. So the first project I need to mention is my autobiographical project, including writing and a film.

During post production, I wrote “The Size Doesn't Matter”, an entertainment novel inspired by a true story with business theories as a side gig. The key character is based on me, but never mentions my experience with sarin gas attack and Mum. A large email magazine company's editor approached me to develop it into an email magazine series with him, so I would like to develop it, hoping it would become a film afterwards.

I feel I am with too much of self-consciousness having two projects which have a character based on me. I wrote another story last year. It is a fictional story. I have not published it yet. I want to develop a script and make a film.

When you make a film, you need other player's participation in the project. So let's see what comes first.