Kaori Sakagami was born in Osaka in 1965, and studied at the University of Pittsburgh. After returning to Japan, she started working as a director for numerous TV documentaries. Since 2001, she has been a Visiting Associate Professor at Hitotsubashi University. Her first feature length documentary LIFERS: REACHING FOR LIFE BEYOND THE WALLS (2004) was awarded at New York International Independent Film and Video Festival, while her following film TALK BACK OUT LOUD (2013) was shown at various international film festivals. In her books as well as in her films, she often deals with therapeutic approaches toward experiences of violence.

On the occasion of her latest film, “Prison Circle” Screening at Nippon Connection, we speak with her about the penal system, Shimane Asahi Rehabilitation Program Center, TC program, various inmates, the whether one is born or becomes a criminal, and many other topics.

You shot two documentaries about the penal system in the US and spent six years tryingto get permission to shoot inside a Japanese prison. When you got that, you spent twoyears shooting inside Shimane Asahi Rehabilitation Program Center. Why? What is that picks your interest so much about prisons?

Just as Dostevsky says,“The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons,” prison is a symbol of society. You can see its culture, values, and social norms especially on how it sees and deals with social deviants.

I have filmed multiple prisons as well as rehabilitation programs for ex-offenders mainly in the US since the 1990s, and I have observed many group discussions among inmates/ex-offenders. I learned many of them have experienced adverse childhood and have suffered greatly from trauma that has gone unnoticed for a long time. At the same time, I have seen so many people who have come to terms with their victimhood and then started to own up to their crimes through the process of the therapeutic community (TC) approach. But these were in the US and I was not sure if this method works in my society.To tell you the truth, I doubted it, simply because Japanese prisons were too strict to allow inmates to talk freely and we did not have any post-release rehab milieu either.

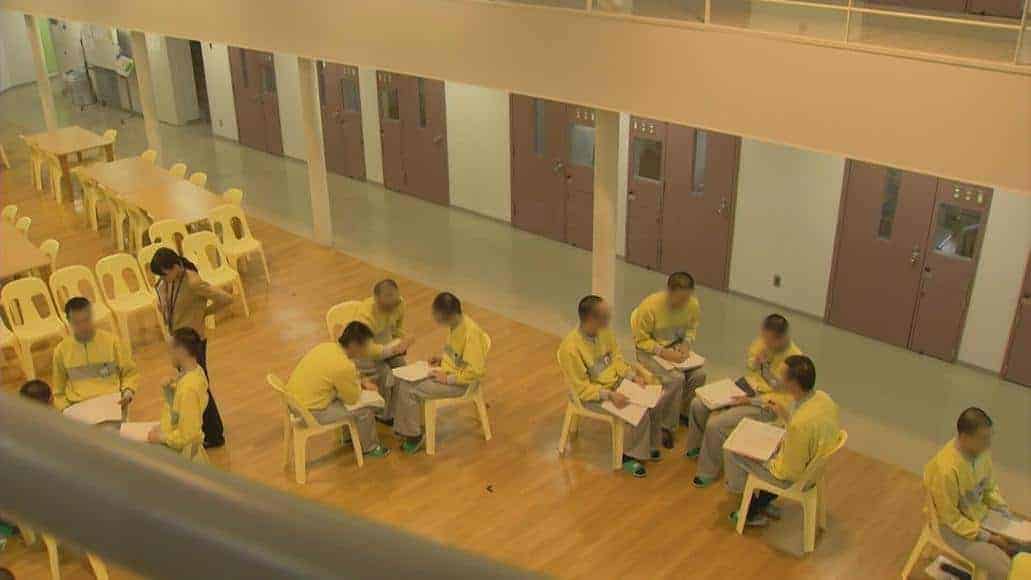

So, my initial visit to one of the newest prisons, Shimane Asahi Rehabilitation Program Center in 2009, just a few months after its opening, was eye-opening. I was allowed to spend a couple of days in Shimane Asahi's TC Unit, where 40 inmates live and work together, and spend 12 hours each week to work on themselves by talking to each other. I witnessed authentic talking circles. I was totally shocked by the fact that it was working in a Japanese prison setting. I got curious how it really worked and also, I wanted to let people know about this place. I decided to make a documentary film in my first stay.

Is it true that the inspiration of implementing TC in Japan came from your film “Lifers: Reaching for Life Beyond the Walls”?

Yes. A director from this new prison project watched my film LIFERS at the theater in 2004 and contacted us. He was just assigned to the project from a major construction company. He was moved by the film and said that he wanted to introduce the same model into the new prison so he needed our support. Back then, I was totally against the idea of private prison so I declined to help him. The guy turned to some other academic figure to help bridging with TC in US (Amity Foundation) and successfully introduced the model into Shimane Asahi. I was invited to visit Shimane Asahi in 2009 and found out that they even had adopted my film LIFERS as part of their curriculum. In fact, the first thing inmates do after being admitted is to watch “LIFERS”. Isn't it something?

At my first visit, I got a flood of questions from inmates about the film. One of the protagonists of LIFERS is Reyes who had been denied his parole and I still remember this Japanese inmate asked me if Reyes was ever released. When I said he had left prison, the whole classroom got full of applauses and this guy burst into tears. This image is still stuck in my mind.

What are the main differences between US and Japanese correctional facilities? What is your opinion of the Japanese penal system?

Japanese prisons are super strict. Imagine the concentration camp during the war period or the military boot camp. Your head has to be shaved. You have to march and move in a certain manner. You have to shout the numbers. You are not allowed to speak at all except a short free time after dinner. You have to raise your hand and get permission for anything you do. If you break any of those rules, you get punished. Japanese prison is a machine of taking away your identity and stamping shame, I think.

US prisons are no utopia either. They have their own faults. But I think they are more flexible and allow inmates to keep their identity at least. As many of US institutions are, their prisons have space for the possibility of change, whereas Japanese prisons allow very little space for a change.

Why did you pick those four inmates to focus on?

We were not allowed to speak to inmates nor staff alone. With inmates, the personal interviews I requested were the only opportunity for me to talk and establish relationship. Only 30 minutes for each person and the interviews had to be done within program hours so I had to give up shooting the program when shooting interviews. I had to choose minimum. But you can lose anyone at any time if he got in trouble, without any explanation. So I picked 15 inmates for interviews over a two-year-shooting period. Two were kicked out from the TC Unit in the middle of the shooting, and many left after 6~9 months, which is not enough. For example, I had a couple of guys who had committed sexual crimes, and I really wanted to include one of them but I did not feel I had enough material to represent them adequately nor I felt being trusted from either of them. So I did not include them.

I ended up with four protagonists because I felt I had gained some level of trust from them, especially through interviews and because I had enough material from them to run stories.

Were you at any point shocked of what they talked about? Particularly their years as children?

Yes, constantly. I was used to hearing horrible abuse cases from filming and researching in US prisons, so for this project, I was struck by neglect, more than anything.

Sho was left alone in the evenings since he was 4 years old, because his single mother worked at night. I could not include all the details but he had asthma, so he had to manage himself with asthma attacks and high fever, which happened quite often. Only 4 years old! Masato had to survive without dinner while his step-father was being served by his mother in front of him. He ended up stealing food daily. No wonder! Taku was beaten up by his father every day and was almost killed many times. He was saved once because he was arrested for his stealing at the age 7 and told the police if he was taken back, he would be killed. He was allowed to stay at a shelter but only for a short period, then sent back to his mother who had left his father. But she abandoned him for her new boyfriend. He repeated this going-home and sent-back-to-shelter process. And even after he left home, abuse kept going at children's home. And no staff noticed. No wonder he cannot trust anybody! Ken was bullied at school since 4th grade up to 11th grade, and nobody tried to help him. He is 27 years old now but he still gets paranoid when someone stands behind him because he fears of being pushed. I would be too if I was him!

What I am trying to say is that the level of neglect, from individual families to the social system is so intense. These guys have had almost no interventions, at any stage. When they had any, it was superficial. I would like to name contemporary Japan as “the society of neglect”.

The documentary seems to state your opinion about the question of whether criminals are born or are made, which obviously lingers towards the latter. Was that one of your purposes in the film?

Yes, that is one of many points I wanted to address. And it is not just my opinion or impression but there are many evidence-based research to support the core of my film. As you probably noticed, I take a fairly long time to make a film. “Lifers” only took 2 years but my second feature film “Talk back Out Loud” took almost 8 years to complete, and this one took 10 years since its inception. Of course I did not intend to take such a long time and I faced many obstacles in making it but also, I think we need enough time to do research and observe transformation and think things through.

What is your opinion of TC? Do you think it works, even outside such a controlled environment as that of the prison? At one point in the meetings of the people that previously participated in TC, you show a man who has not managed to change truly and still has problems with his life. Why?

I have spent a fair amount of time at the TC facility in US. I was never admitted but I have hung out with them enough to understand its essence and see the change over time. And I still keep going back. Before filming took place, I used to go to Shimane Asahi as a guest lecturer and gave numerous workshops every year. Japanese style TC is a bit different from the TC I know in the US, but I feel the essence is the same. I think it is effective but it does not affect everybody. I think you can easily call some program TC but it often is not. I would not go into depth here, but I am not a TC promoter. I consider myself as an advocate for a humane approach for transformation. TC certainly offers us an important approach – using group for transformation of everybody and we can all learn the essence of it. But it does not mean that we need to build up TC facilities per se.

I showed the guy in trouble making confession over his wrongdoings after being released because that is the reality. Post-release facilities tied to the probation system where this guy used to stay are almost like prison – very strict and they are only expected to work. There is not really a follow-up program outside prison setting. Life in prison and outside is so different and they surely need support, but there is almost none. But this guy had at least this circle of former TC members and staff to meet regularly and talk honestly about each other. One of my favorite scenes is when his former peer suggested that they all would be a witness for the guy when in trouble, to keep their eyes on. It is a caring and supporting circle, rather than surveillance. And this type of relationship is very rare but crucial. I am still in touch with most of them including the guy (and he still is in trouble to some extent) and they all care about each other. This is one of the very positive results of the TC Unit, I believe.

Shimane Asahi functions as a collaboration of state and private funds. Do you think this is the nominal way for correctional facilities to progress in the future?

Not sure yet. I think the Ministry of Justice really wants to keep power. What I have seen so far is not an authentic collaboration of state and private sectors but the state's using private resources. Although I was totally against privatization of prisons before, I learned that the Japanese style PFI (Private Finance Initiative) is not the same with private prisons in the West. I hope the authentic collaboration between different sectors would happen so that a more effective and humane system can be established. However, in reality it seems difficult…

How much footage did you end up with after two years of shooting and how much time did you spend editing?

I have shot outside prison settings as well, so everything included, around 400 hours worth of footage. Inside prison alone, I spent between 24 hours~84 hours a month. Since we are strictly controlled and conditioned, for some days, we were only allowed to shoot for one hour or so and the rest of the day, we were standing at the corner of the room where programs were going on. Very frustrated and upsetting, you can imagine.

Editing was another tough process and took me two or more years. First of all, we were not allowed to take footage outside prison. I negotiated and took more than 6 months to get permission to bring them home. I watched some footage while we were shooting, but I did not start editing until the shoot ended.

Since we were banned from showing their faces and forced to change the tone of their voices, I felt like being gagged. After completing the shoot, I started taking notes but very slowly and it took me one full year to really start editing; too much worry and too much disruptions so that I could not focus.

After years of negotiations with the Ministry of Justice, I got finally the ok with using real voices of inmates in the fall of 2018 and since that point, I could finally focus on editing.

Frequently, the camera focuses on the hand of the inmates. Why is that?

Many people notice it. Because we were restricted about showing people's identity: face, tattoos, and scars were supposed to be hidden, we had to find ways to show their emotions somehow. So we had to watch their body language carefully and hands stood out the most: they are more expressive than any other parts of the body.

What is your opinion of the Japanese movie industry at the moment, particularly regarding docs?

It has been tough. I think the documentary industry is pretty much two-folds – TV industry and a mini-theater venue. I worked in the TV world between 1992 and 2001 and landed into the film venue in 2004 because I was pushed out from the TV world. I was a total stranger and very few theaters showed my film because it was a documentary. Now, many mini-theaters (art-house) tend to screen documentaries which were aired on TV once and re-arranged for theater. TV is still in its own world but expanding it to the theater realm. For independent filmmakers like me, it is getting more competitive and a constant struggle to find funds (almost no funds so we end up working two, three different jobs…). But in any case, that many documentaries are shown at theaters is a good thing.

At the time of Covid-19, mini-theaters are struggling, but mini-theater-aid movement was born and there is a new platform of online-theaters where you can choose to pay for a particular theater and watch a film online instead of physically going to visit. “Prison Circle” joined this online-theater and I am seeing its many pluses. So, we have to be creative and come up with multiple platforms where we can watch many more diverse documentaries.

Are you working on anything new?

Yes. I have a couple of projects but I can only tell you one of them. It is a short animated documentary by using the real voice of women inmates in US, but it will totally look different. I was not a fan of animation but after I worked with an animation artist for “Prison Circle”, I felt the charm and power of animated doc. During quarantine, I worked on the old footage I had and I have had online discussions with a young and experienced animation artist. It will be an exciting collaboration work!