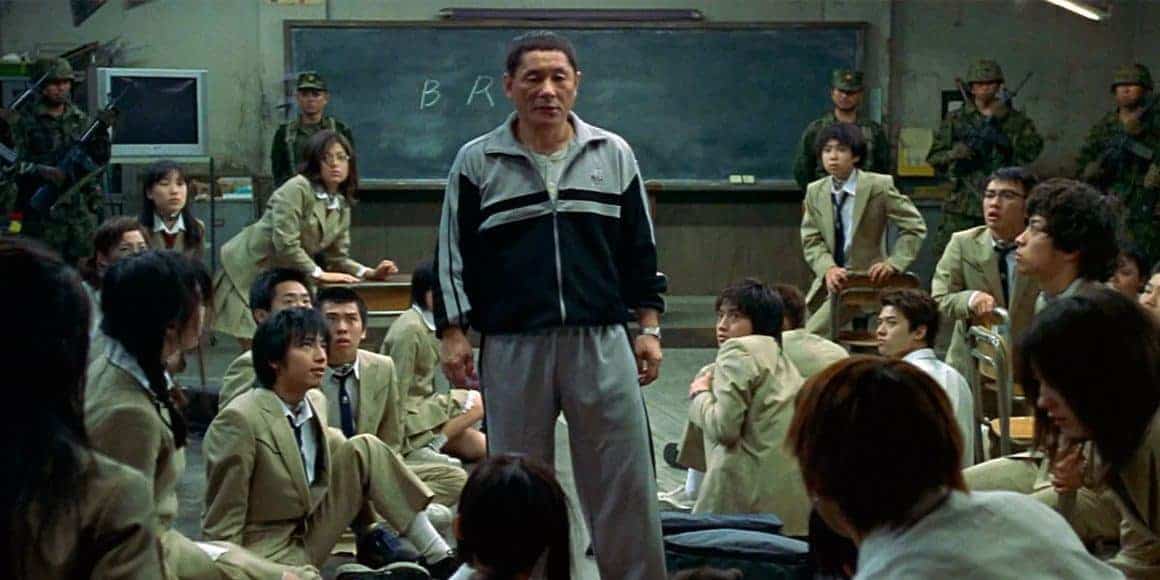

7. Kitano in Battle Royale (Kinji Fukasaku, 2000)

The dystopian classic provides us with a fantastic performance from Takeshi Kitano. The lone adult voice, aside from flashbacks, is a perfect counterpoint to the teenage emotion we witness. It is a darkly comical portrayal where his taunting of his former students and glee at revenging himself at the outset sets him up as a representative of the oppressive authority. By the climax, we have a more nuanced characterization. Kitano is able to elicit sympathy and even pathos in his performance as we come to realize that he is just as trapped on the island as the pupils are. His family relationship is ruined with a distant wife and a daughter that has no interest. The slightly perverse interest in Noriko is shown to be almost paternal as we come to realise he sees her as his salvation and escape through death. Kitano's presence makes these contradictions work and even absurd visuals such as the holding of a children's brolly, work in the context that ultimately he is no different to the students whose deaths he oversees. A brilliant tragicomic portrayal which is often lost when discussing the picture. (Ben Stykuc)

Buy This Title

8. Zatoichi in Zatoichi (Takeshi Kitano, 2003)

Although Kitano 2003 directorial effort is quite popular among cinephiles, his interpretation of the story surrounding the iconic blind masseur, wonderfully played by Shintaro Katsu in over 20 films, is somewhat controversial. However, Takeshi Kitano's take on the role and the world of Zatoichi is one that is strikingly modern and unique, blending elements of musical and comedy with a main character whose hair is dyed blonde. If you can accept this is no longer the Zatoichi you knew, you are rewarded not only with a hugely entertaining film, but also a performance that combines the contradictory elements of the character, his stunning skill as a fighter, his uncanny perception and the character's stoicism. (Rouven Linnarz)

Buy This Title

9. The Yakuza in Tokyo Eyes (Jean-Pierre Limosin, 1998)

Takeshi Kitano steals the show with his nosy, obnoxious, and dangerous behaviour that borders on bullying, only to be changed to something completely different and equally unjustifiable by the finale. Kitano is as good as always, despite his brief time on screen, but the irrelevance of his appearance actually makes his presence more of a gimmick than an element that adds to the narrative. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

10. Kikujiro Takeda in Kikujiro (Takeshi Kitano, 1999)

This was the first time Kitano succumbed to criticism for the violent element in his movies, deciding to shoot a road movie without any violence at all. However, his character seems to play with the notion, since his eagerness for action is almost constantly visible and presented through his funnily harsh words and attitude. The same applies to the gender reversal aspect, since quite frequently, it is Takeda who acts like a child. The combination of the two result in a rather difficult role, which Kitano, however, portrays with ease in one of the most nuanced, sensitive, and funny performances of his career. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

11. Machisu in Achilles and the Tortoise (Takeshi Kitano, 2008)

“Achilles and the Tortoise” might be one of Kitano's the most bitter-sweet stand-outs. With a monumentally melancholic facade running through his face, the contemporary painter he embodies in the film is both convincing as an artist in the constant pursuit of the non-achievable perfection, as well as amusing, because the effect is nowhere near and the pursuit is nonetheless hilarious to watch. This, of course, brings the scrutiny of the hardships of being obsessively indulged in artistic body of work, one that determines one's life and brings rather frustration over satisfaction. Kitano's minimalistic frequency of emotions surely serves right the ambiguity of his character, as he drifts between van Gogh's vibrant acrimony – rather silent, not so much delved in anger – and a gloomy sense of detachment; realization that comes to the artist, when one figures the elusiveness of art. This is less self-oriented Kitano, more focused on the essence of what it means to be, respectively, an artist, and a philosopher, reflecting on the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise in the context of quality of art and its commercial aspects – they might eventually never overtake each other. Thus, the frustration – reflected on Kitano's well-known motionless face – has a bitter taste. (Lukasz Mankowski)

Buy This Title

12. Yoshitaka Nishi in Fireworks (Takeshi Kitano, 1997)

When given the opportunity and the circumstances of the character they play allow it, there are some actors who would tend to go over the top, making their performance melodramatic and filled with pathos. On the other hand, there are performers who seem to confuse acting with physical transformation, essentially playing masquerade or any other children's game, letting their hairdo, costumes or make-up do the acting for them. Sadly, many institutions, such as the Academy of Motion Pictures, award these kind of performances quite often with the highest honors.

With regard to Takeshi Kitano's performance in Nagisa Oshima's “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” Scottish actor Tom Conti once said, the Japanese actor, who plays the role of the sadistic Sgt. Hara, had many opportunities to go in the aforementioned direction with his acting, but did not since the circumstances pretty much do the job for you. Instead, Kitano plays Hara as someone who has accepted his fate, adding gravity and dignity to a his performance.

Similar things can be said about Kitano's performance in “Hana-Bi”, arguably the role most Western audiences associate with the actor. During the course of the story Nishi endures much emotional and physical pain, the terminal illness of his wife, being chased by the yakuza as well as the tragic shooting with a suspect, causing the death of one colleague and the grave injury of another. Nishi buries his pain behind the tinted glasses of his shades, his hands in his pocket and an expression seemingly unmoved by the events, while only the twitches of the left side of his face (due to Kitano's motorcycle accident a few years ago) give us a clue about what kind of feelings he goes through inside.

Kitano as Nishi is not one who needs to transform himself or who needs melodrama. In fact, he stays silent for the majority of the story, adding to the shock of the viewer when violence suddenly erupts. It is a performance showing a man who endures the pain, who has made his peace with whatever happens to him and follows a path, much like a Japanese samurai, leading to an inevitable end. Altogether, this makes Kitano's performance so powerful and an example for how the idea reduction and doing less can have great effect (Rouven Linnarz)

Buy This Film