Shinya Tsukamoto is a particularly significant filmmaker for the contemporary Japanese industry, since his “Tetsuo” turned international interest once more toward the country's cinema, after a rather disastrous decade during the 80s. Furthermore, it created a completely new audience for Japanese filmmakers, this time not among those who had previously dealt with Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi, but younger ones, who were searching for films that would eventually take the title of cult.

Buy This Title

Tom Mes paints a rather thorough and analytical portrait of the prolific artist, starting from his childhood and encompassing all his capacities, that also include stage plays, acting and voice acting, particularly for TV and radio commercials, which Tsukamoto still refers to as his main source of income. In that fashion, the book begins with how Tsukamoto grew up and his first influences (Ultra Q), his relationship with his brother, mother and the rather difficult one with his father and the first films he shot while in high school. The influence the era, the environment and his family had on his filmmaking becomes evident even from this first chapter, adding to the thoroughness of the portrait and explaining much of the aesthetics implemented in his works.

The second chapter deals with his days as a stage play director, which also played a crucial role in the way he shot and particularly produced his films. The PIA Award for “The Adventures of Denchu Kozo”, which signaled his return to cinema, and the subsequent success brought by “Tetsuo” are the focus of the next chapters. In each of the next parts, Mes deals with one of Tsukamoto's movies, following the pattern of (I) story of production and shooting, including many trivia (the interactions with Jodorowsky are particularly interesting), (II) analysis of the film, and finally (III) the director's own opinion of each title.

This approach allows Mes to present the films quite thoroughly, highlighting not just the movies themselves, but also the path and the hardships Tsukamoto had to face each time. Particularly the first part each time includes information that was completely unknown, at least to the Western audience, and also highlight the distinctly independent path the filmmaker followed for most of his movies. His method of putting his own money, borrowing from friends, taking sponsorships for the equipment, and using his friends and colleagues (and himself) for the crew and cast emerges here in all its glory. At the same time, all the first parts also include the contribution late Chu Ishikawa had on the films, and the way he cooperated each time with the director to come up with all these great tracks. Lastly, through these stories, the importance the European film festival circuit played in Tsukamoto's career as much as on the reinvigoration of Japanese cinema also becomes rather clear.

Through this information, Tsukamoto emerges as a man almost heroic, but Mes does not allow the book to become a eulogy. His faults, some of which he admits and some not, and particularly the frequent fights he had with members of his crew are also highlighted here, with the foreword by Takashi Miike that refers to the director as “tough and generous madman” fitting Mes's portrait completely.

The analysis of the movies is also excellent, with the motifs and the thoughts Tsukamoto wanted to implement to each title being explained clearly, eloquently and thoroughly. The importance human body plays in all his films is underlined to the fullest, along with his transition from his cyberpunk days to the different paths he followed later in his career.

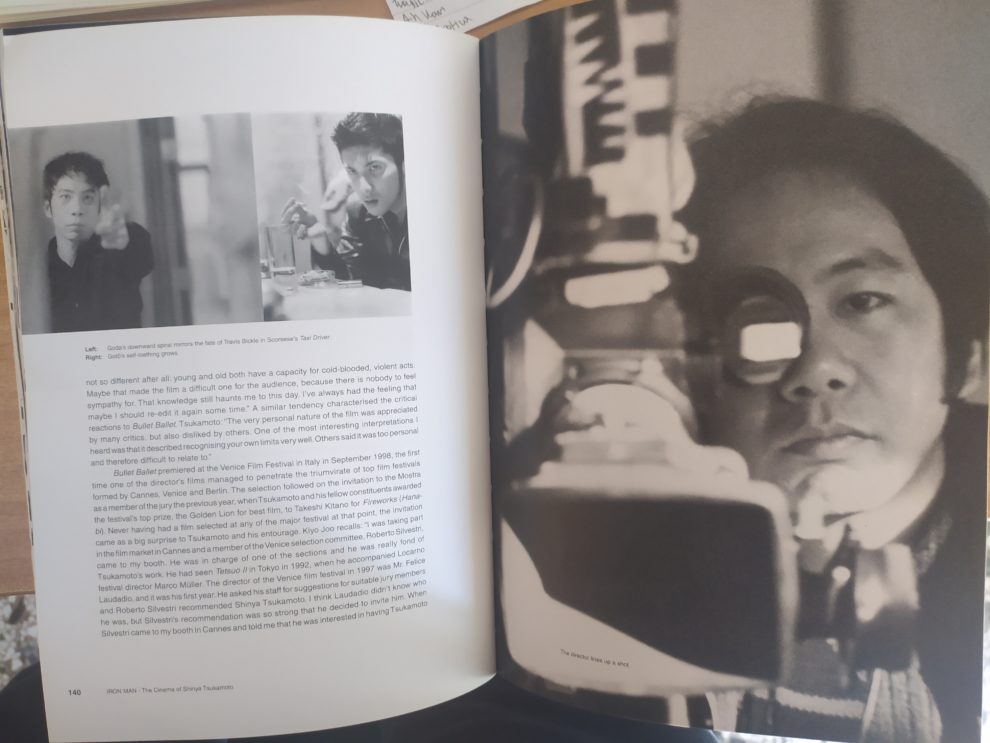

Tom Mes's writing is easy to read but quite rich at the same time, and his ability to make essays look like novels in terms of how enjoyable they are to read finds its apogee in “Iron Man”. However, the very small letters of the FAB Press publication definitely need some getting used to and the notes (although few) are once again in the back of the book, making the edition somewhat hard to read, at least in the beginning. On the other hand, the overall format, including the front and back covers, is impressive, and the plethora of images in the book (particularly the colored ones in the middle) enrich the edition significantly, while also accompanying the writing in the best fashion.

“Iron Man. The Cinema of Shinya Tsukamoto” provides both a great introduction and a companion to Tsukamoto's filmography up to 2004, highlighting the man as much as much as the artist in the most thorough way.