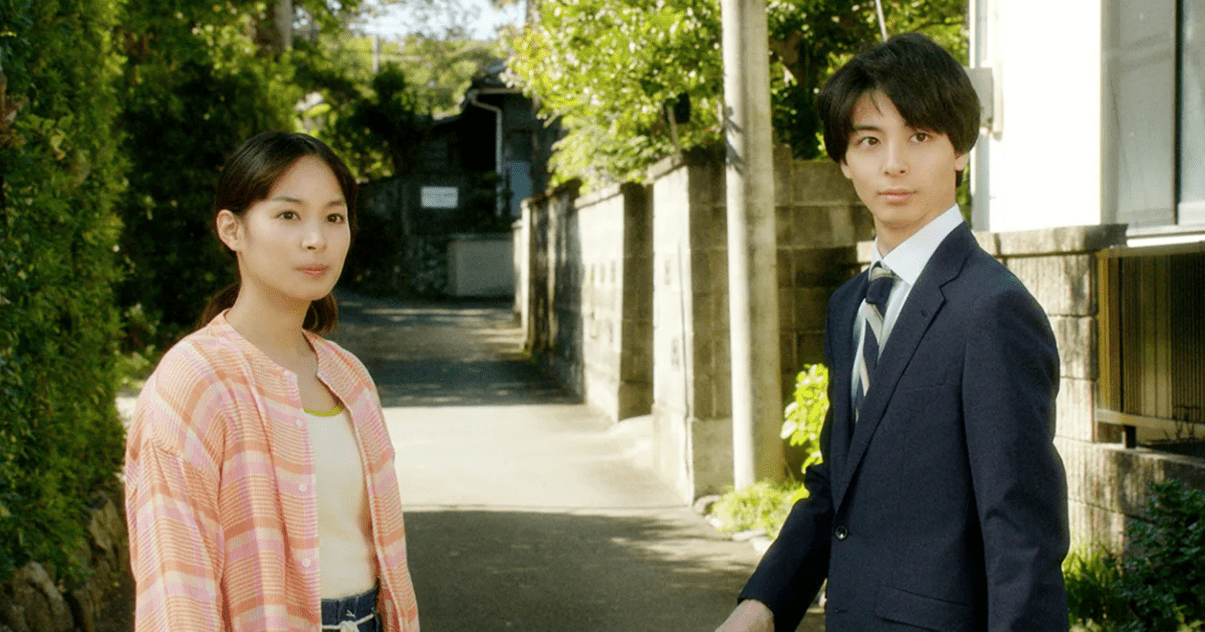

The 3/11 catastrophe is a reoccurring topic in recent Japanese cinema. After a slow start, the industry seems to be confident enough to tackle the trauma. It almost took nine years for a big production company to release the premier Fukushima-themed blockbuster, “Fukushima 50” by Setsuro Wakamatsu. In the same year Nobuhiru Suwa, film director and President of the Tokyo Zokei University, presents “Voices in the Wind”. For the first time in 18 years, Suwa returns to his home country to tell a devastating and haunting roadtrip drama about 17-year-old Haru, who lost her parents in the tsunami and travels to the place that once was her home.

Voices in the Wind is screening at Camera Japan

In the northern coast town of Otsuchi, there is a white telephone booth to which over 30.000 people from all over Japan have come to speak to the “loved ones” that were lost in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Haru hasn't been to Otsuchi in eight years. She has been raised by her aunt Hiroko in Hiroshima. When Hiroko gets ill, Haru decides to hitchhike to Otsuchi. Along the way, she meets all kinds of people, who affect her.

Nobuhiru Suwa brings together a prestigious cast and crew. Takahiro Haibara shoots the film using a static camera. His realistic style known from Haibara's award-winning work for Kazuya Shiraishi (“Birds Without Names” 2017, “The Blood of Wolves” 2018) is mixed with the minimalistic editing done by Takashi Sato (“Farewell Song” 2019). This technique complies with Suwa's improvisation skills and gives the actors room for their own ideas. The realistic concept is further approved by a saturated color grading, which adds an ultra-sharp look to the images.

On the actor's side, we see an excellent cast. Serena Motola's face is a canvas that presents the very core of the film. Her character is a carrier of the catastrophe. In the moments of encounter, she reminds others of the tsunami and the consequences. Past and present are collectively bound in her presence the same way the movie tries to keep up the memory of the disaster. Haru becomes a metaphor for the meaning of the film itself. As a living memory of that incident, she is tangled up in an inner and also outer search of her roots. This search is not shaped by movement. Haru sits on benches at parks and train stations, somehow caught in-between. The extreme focus on her performance happens at the expense of pacing, which is a little slow. Besides Motola, there is Makiko Watanabe (“Still the Water” 2014) as aunt Hiroko, Toshiyuki Nishida (“The Magic Hour” 2008), and Tomokazu Miura (“Adrift on Tokyo” 2007), who round up a well balanced cast consisting of veteran and newcomer actors.

Kind of like Akihiko Shiota's roadmovies (“Lifeline” 2016), Suwa describes a female longing for home. He also discusses the stigma that sticks to the question of origin. “Voices in the Wind” contextualizes this matter not only with people from the disaster areas but also with foreigners in Japan. This makes the movie even more interesting and unique and extends its message to a universal meaning.

As Haru returns to Otsuchi, the camera gets more lively and shaky. The final sequence in the telephone booth is masterful. Twenty minutes without editing and raw footage of Haru's performance require trust in your cast and true faith in the power of cinema. It gives an account of a fearless filmmaker and at the same time wraps the viewer in a spectral blanket of sadness.