In the spotlight since his starring role in Kurosawa Kiyoshi's Bright Future in 2003, Joe Odagiri has amassed an extraordinary filmography, working primarily with indie auteurs rather than big-studio directors, and creating a range of unforgettable characters, each one distinct from the last. Active overseas since 2006, he has also gamely performed in English, French, Korean and Spanish. Among many other awards, he has received Best Supporting Actor at the Japanese Academy prizes for Blood and Bones in 2004, and Best Actor for Sway in 2006.

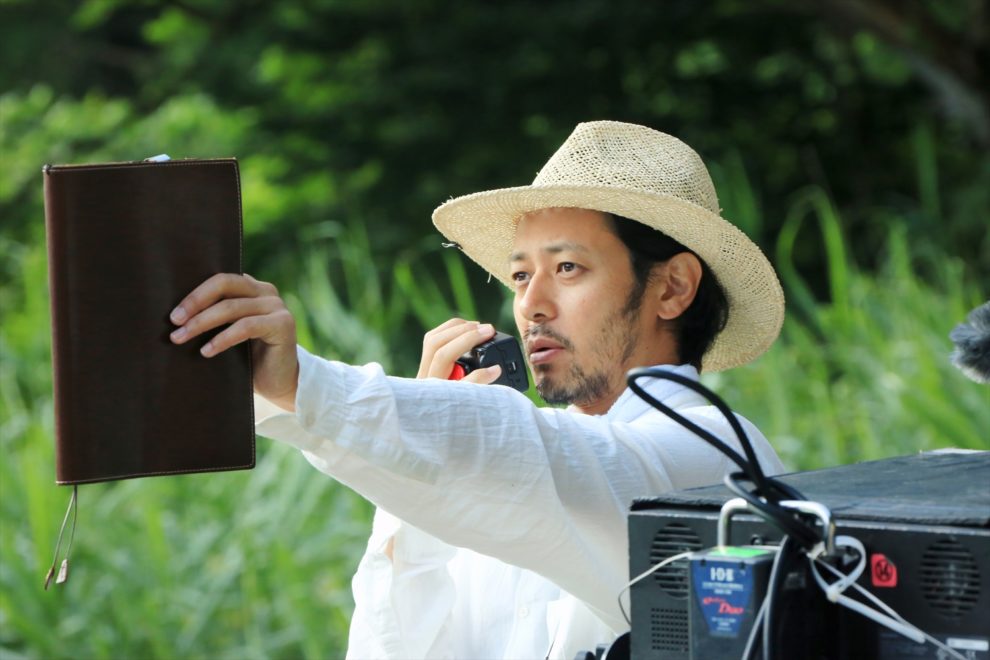

On the occasion of his feature debut, “They Say Nothing Stays the Same”, screened at New York Asian Film Festival, we speak with him about his experience as director, working with an international crew and particularly Christopher Doyle, shooting in Niigata, and many other topics

What was the motivation your first feature film as a director?

Meeting cinematographer Christopher Doyle started this project. I was invited to work with him on a film he directed (The White Girl, 2017) and we spent about a month on set together. I felt like I was back in school, and the way they improvised and expanded on the spot without sticking to a script, it was like this creative urge that had been smoldering inside me was growing stronger and stronger each day. One day Chris said to me, ‘Why don't you direct? If you direct, I'll shoot. I started to think about doing something interesting with Chris, and I chose this film among the several scripts I had written, thinking that it would be fit if he was going to shoot for me. I knew that Chris would be able to capture the beauty of Japan. I believed that, with his unique sense of color and composition, he would be able to create a world that was more than just beautiful.

How did your experience in acting helped you as a director?

I think being an actor myself has helped me a lot in directing. As a peer, I can often understand what actors are thinking, what they're feeling, what their mental state is at the moment, what they're trying to do, what they want, etc. Because of that, I try to choose the right direction for them. Because some actors are the type who want everything explained to them, and others don't want much direction.

As for acting, I'm a professional in one way or another, so I never get fooled by fake acting.

The cast in “They Say Nothing Stays the Same” is excellent. How was the casting process? I also noticed a small cameo by former YMO-member Haroumi Hosono. How did that came about?

I reached out to people I trust as my peers. There are different types of actors, but the actors in this film are those who are not bound by the size of the role or the business aspects of the role. They are all hard working and sincere in their acting. I didn't choose them for their popularity or to increase the number of film-goers.

As for Hosono-san, I myself like his music and his appearance. I believed that his philosophy and his core values would have a big impact on the character's presence in the film.

The acting seems very nihilistic to me. What kind of instructions did you gave the actors?

I tried not to explain too much to Akira Emoto, who played Toichi. Conversely, to Ririka Kawashima, who played Fu, I had been giving her acting lessons for more than half a year and gave her detailed advice on set. There are things that only actors can understand, so I think it's one of my advantages.

The cinematography is done by Christopher Doyle, mostly known for his work with Wong Kar-Wai („Fallen Angels“ 1995). The soundtrack is composed by the young Armenian pianist Tigran Hamasyan. Was it important for you to have an international crew? Why did you choose them?

The purpose wasn't to gather international staff, it was just that they were people I liked and wanted to work with. And coincidentally, they were from overseas. That's all.

When I was writing the script, I wanted some non-Japanese cinematographer to participate. I thought it would be possible that for a Japanese DP, some of the beautiful scenery is too familiar to capture with an international-standard viewpoint. Chris was just great. His personality, great talent, and love for cinema were all indispensable to this film. We respected each other and it became a great collaboration.

Tigran Hamasyan was great as well. He is known as a genius jazz pianist. But he was humble and warm, and he cared very much about this work. The music he writes has no borders. His music transcends region, race, language and culture. I knew his music would be a perfect match, even for a Japanese film, because his music reaches deeply into our hearts.

Chris and Tigran are both essential to the film, but I think the same goes for all the other crew and cast. I'm grateful for the support they all gave to this inexperienced director to complete this film.

There are many long sequences of water and the surroundings. The setting also reminded me of Duk's „Spring, Summer, Fall, Winder…and Spring“ (2003). What role does nature play in your film?

Where did you shoot the movie?

The area where the film was shot is called Niigata. When I first saw this place, I had a strong impression. The craggy, rocky terrain looked like Mars, and it didn't look like Japan. It's a place where one would think, “This is not an easy place to live.” And it's a place that will help us to think about the life of Toichi, so we chose this place. I thought one of the most important themes for this project was the relationship between humans and nature. So I thought it was necessary to surrender to nature. The climate, temperature, and conditions were all very challenging, but I think I was able to project a strong impression of that harshness and the relationship between humans and the environment. Japan's four seasons are beautiful and produce pretty sceneries. But I was thinking I had to portray not only the beauty of the scenery, but also the harshness and cruelty of nature.

What was the hardest part of the shoot?

The hardest part of the shoot…maybe I'm exaggerating, but it was everything. I don't think there were many things that went the way I wanted on the shoot. I had a lot of stress, and after the first week, I had almost 10 canker sores and I couldn't eat anything except [jello] and soup. And drastically I lost over 10 pounds. I used to be asked, ‘Isn't it fun being a director?' No. It's ridiculous (laughs). There was a lot of stress, a lot of pressure, and a lot of headaches on a daily basis trying to get the script to work. The crew helped me get through it, but if I was alone, it was a crazy task.

But it came from the challenges I set for myself. From the time I was writing the script, I limited the scope of what I could portray by setting the time period 150 years ago. I created visual difficulties by limiting scenes and transitions so the story could proceed only on a river, a boat and a hut, minimized the number of actors as much as possible, and kept the story minimal by making it difficult to depict too dramatic story developments… I wrote the script in a way that added restraints on myself.

I wanted to create a situation where I had to face the film much more seriously, without it being easy.

I think this film is full of those challenges.

How would you describe the relationship between the old man, Toichi, and the mysterious girl named Fu?

Although not much is said about Toichi's life, I'm sure he spent a lot of time as a boatman, most of it on board. It must be a modest and quiet life. Perhaps Fu had her own life, and they were never meant to meet each other. I think their encounter caused a lot of things to go wrong gradually. The last choice made by Toichi was the moment when he made his own active move instead of the passive way of life he had been living.

One of my favorite sequences is the secret funeral of the hunter in the woods. I liked the idea of sacrifice and the whole concept of paying respect to nature. How did you came up with that idea?

Among Japanese people, there are many who say, “I want to be buried here after I die,” or actors say, “It's my dream to die on stage,” and so on. I feel that Japanese tend to associate their own deaths with certain places. I think there is also a sense of returning back to the places that had great influence on you and places that have been really kind to you. I think that's what led me to this scene, and I was also interested in Tibetan bird burials.

You went to the California State University in Fresno to study acting. How was that experience and is it true that you originally intended to enroll for film directing, but ended up in the acting class?

I think that spending my sensitive teenage years in the United States is a great asset for me. I experienced a lot of cultural gaps and learned the diversity of values. The things I learned in America, especially about art, music, and movies, are the foundation of who I am today.

It's true that I made a mistake in my major. But if I hadn't made that mistake, I wouldn't have become an actor or a director. Ironically, I feel that becoming an actor brought me closer to becoming a film director.

I was the only foreigner in the acting course. I couldn't speak English well, and every day was a struggle. In my Shakespeare reading class, I had to look up nearly 10 unfamiliar words in one line in the dictionary, and it was probably the time of my life that I learned the most. It was just filled with things that I could not experience in Japan. I think that I learned to think a little bit more globally.

What are your future projects?

There are so many great directors out there, so what can I do? I'm inferior. I believe that this is the pursuit of originality. I am sure that there are works that only I can make. I'm not good enough at adapting novels and comics into films, and I think there are more suitable directors who should be in charge of those.

I want to find stories that only I can write, and if there's something I'm interested in or want to portray. I'll continue to write scripts and make original films. I can't tell you much about it yet, but I'm getting ready to shoot this winter.