Director Tsai Ming-liang is one of the most distinguished directors of the new cinema movement in Taiwan. Born in Malaysia, he moved to Taiwan at the age of 20. There he graduated from the Drama and Cinema Department of the Chinese Cultural University of Taiwan in 1982 and went on working as a theatrical producer, screenwriter, and television director in Hong Kong.

His first feature film was “Rebels of the Neon God” in 1992, a film about troubled youth in Taipei, and with his second film, “Vive L'Amour” in 1994, won the Golden Lion (best picture) at the 1994 Venice Film Festival. Along with Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang is one of Taiwan's most prominent Taiwanese directors.

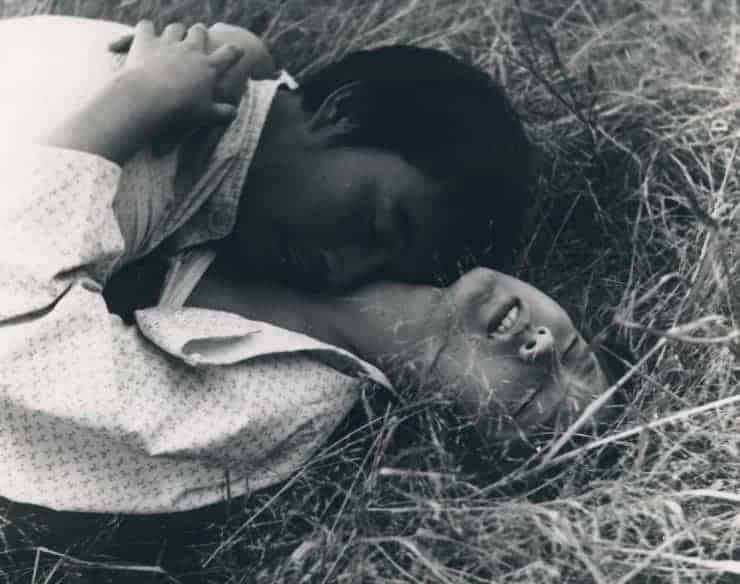

A puppet master of slowness, a monk dwelling in the eeriness of time, a philosopher of human loneliness and restlesness of a body. When water is peacefully falling down, drop by drop; when lovers say one last goodbye to each other; with cinemas having their last fade-out on the screen, the audience staring at it, with tears in their eyes; when the music box waves with tunes for the last gaze between those who want to fall in love, but are lost in their solitude. This is where Tsai Ming-liang's films plunge. Delicately and slowly.

On the occasion of MUBI streaming a number of Tsai Ming-liang films, we present ten of the greatest works of the auteur, in chronological order.

*By clicking on the titles, you can read the full reviews

1. Rebels of the Neon God (1992)

“Rebels of the Neon God” is a portrayal of a violent youth. Alienated from society and not willing to fulfill their so-called predetermined way of life, the young adults resort to apathy and violence. The dropout kid, Hsiao Kang, starts to follow the rebellious Ah Tze, vandalising his scooter and enjoying the act of destruction. But the movie does not judge them. As a fellow traveler, Tsai seems to sympathize with its characters. (Alexander Knoth)

2. Vive L'Amour (1994)

“Vive L'Amour”, literally “Long Live Love”, is an ironic title for Tsai Ming-liang's sophomore feature, since there's nothing remotely similar to love within reach for any of the three protagonist. Regardless, it is a terrific showcase of not just the director's works but also the Taiwanese New Wave in general. The final scene, a more than five minutes long one take featuring May Lin, an iconic Taipei location and, yes, an intense palpable loneliness, will surely refuse to leave your minds for days on end. (Rhythm Zaveri)

3. The River (1997)

“The River” is an enigmatic family drama about sexuality, repression and the resulting pain that comes from the experience of pretense and dissatisfaction. Its slow pace may be insufferable to some viewers, but the lasting effect of Tsai Ming-liang's third feature on the viewer may be quite profound. (Rouven Linnarz)

4. The Hole (1999)

While this film could be read as Tsai's nostalgic gesture toward the past, he rejects this interpretation of his works. In an interview he did with a Malaysian-Taiwanese film scholar Song-Yong Sing, Tsai says that in his movies, he is interested in showing how things he has used in the past still persist into the present. He is not interested in recreating the past; in contrast, he tries to show that the present consists of things both old and new. I would like to add that his films not only put things with different temporalities within the same frame, but also bring those songs, texts, movie stars and films from the past to the audience who sit in a theater watching his films. He makes the past present to us (I Lin-liu)

5. What Time Is It There? (2001)

On the whole, “What time is it there?”' is a bittersweet film about loss and denial. It is a film about urbanism and alienation, which, exactly like a travelling ghost, tries to get a hold on to human figures. Some people wish to escape from it, so they create their own parallel realities, some desperately provoke it and some think they can get away from it. Unfortunately, it is everywhere. In addition, it is an exceptional cinematic game between space and time and how these dimensions separate but also collide within the human spirit. Though there is stillness and the characters move in a seemingly certain timeframe, we get the sense of a constant movement like time-travelling. The thing is that Ming-liang is encouraging us to wander within this, almost, metaphysical dream, rather than unkindly waking us up or even throwing a bit of light by trying to point fingers and give any kind of answers. (Nicholas Poly)