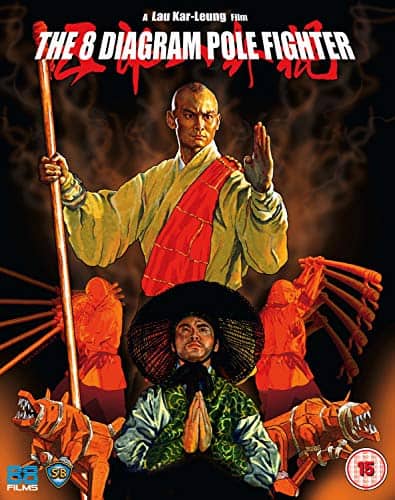

It's a bit of a stretch to label the work of Lau Kar-leung as “arthouse” cinema, as was very much working to a prescribed format during his time at Shaw Brothers. Yet if Chang Cheh's movies were rock' n' roll, all out action blockbusters, then Lau Kar-leung's were more classical. Bringing a purity to martial arts action hitherto not seen. The choreography would be intricate and his work express the more philosophical side of the arts. Yet there is an anomaly amongst his cannon. One that has a viciousness that would rival any Chang Cheh feature. That production is “Eight Diagram Pole Fighter”.

Buy This Title

At the battle of Golden Beach, General Yang and his Son's are betrayed. Only the 6th Brother (Fu Sheng) makes it home, but is driven mad by his experiences. 5th Brother (Gordon Liu) is left for dead and helped to recover by a Hunter (Lau Kar-leung), who later sacrifices himself so 5th Brother can escape. He arrives at Shaolin Temple hoping to learn their martial arts, only to be rejected for having too much anger in his heart. Forcibly taking the rituals, he enters but is unable to control his desire for vengeance. Learning of his survival, his sister (Kara Hui) sets out in search, only to be captured by the villains who betrayed the Yang family. 5th Brother now must face his demons to rescue his sister and restore his family honour.

I liken “Eight Diagram Pole Fighter” to being the dark mirror image of “The 36th Chamber of Shaolin”. Both feature Gordon Liu as an avenging monk from the Shaolin Temple, but diverge wildly in how the character is portrayed. In the latter, San Te willingly submits to the ordeal he is about to enter, gradually shifting his anger into a more benign desire to help others once his vengeance is accomplished. In the former, the 5th Son does neither of these. He forcefully enters Shaolin and undertakes the ritual angrily to the horror of those present. At the conclusion there is nowhere left for him to go. He retains his anger so he cannot go back to Shaolin, nor can he return home despite the pleas of his sister. His fate is to be a wanderer, unable to move on. Here vengeance is no resolution, merely another form of destruction.

The action is equally vicious, matching the dark heart of the narrative. The opening is a theatrical representation of the betrayal of the Yang family, with the father and brothers meeting a bloody demise. So far, so standard. Yet once we get to Shaolin, it takes a more unusual turn. The technique being used is the “defanging the wolves” – ostensibly a way to protect the temple from the predators. In the finale we see monks use this to pull the teeth from the villains. Something straight out of a Chang Cheh piece.

The reasoning behind this darker work comes from the background behind its production. Fu Sheng who was playing the 6th brother and the one who in the telling of the Yang family story is the only survivor, died in a car accident during the filming. The resultant feature has then the feel of grief being expressed through anger in its rewrite. There is no redemptive arc, violence begets violence, with the hero left alone to an uncertain future whilst 6th brother is left insane. It's as if the whole cast and crew poured their collective emotion into the film and it captures an emotion unlike anything else in this genre.

Lau Kar-leung was one of the greatest choreographers in the industry and this film is no exception to the case. Inventive and visually interesting, it captures the talents of his cast magnificently. Despite the brutality, there is almost a beauty to the choreography. A violent ballet of athleticism. Gordon Liu is never as good as when being filmed by his adoptive brother and gets to have a bit more range in his usual monk act this time around. He captures both the inner and outer rage his character feels superbly and is one of his finest roles.

In Kara Hui, we also get another element that differentiates the two directors; portrayal of women. Whilst it is arguable her character here is mainly a plot device, she is allowed to get into the thick of the action. A regular in Lau Kar-leung's work, Kara Hui is a graceful performer who is equally adept at the complex movements he demands. Along with Lily Li, she represents a more balanced attitude as opposed to Chang Cheh's masculine ideology. This is not to say it's perfect however. Even when the women are skilled fighters, the male will still ultimately be the final combatant, relegating her to a supporting role. Cases in point, “Lady is the Boss” and “My Young Auntie”. Still, it's an improvement over Chang Cheh!

Despite the usual Shaw Brothers aesthetic, the choreography makes it stand out as an example of the director's work. Auteur theory is probably not always considered for martial arts cinema, but Lau Kar-leung deserves to be considered as one for the consistent themes that exist in his canon. Even here, the darkest of his features, we have the exquisite choreography that emphasizes the martial arts, women joining in the battle even if ultimately marginalized, and ultimately a reinforcement of the Confucius virtues. The anger demonstrates the futility of learning for the sake of violence, for unless the anger is controlled there will be no hope for a better future. A lesson learned in “Executioners from Shaolin” and emphasized here albeit unintended.

This is a movie that I recommend highly. Coming at the end of the original cycle of martial arts cinema, it is simply one of the finest by one of the true masters. Different from his usual canon, it has a power and rage unlike most and needs to be seen by any fan of the genre.