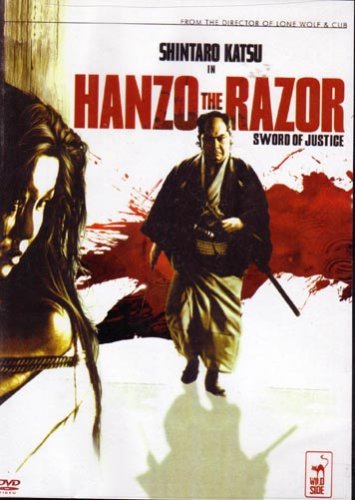

With the Zatoichi series running out of steam (there would be only two more of those releasing after 1972), actor/producer/director Shintaro Katsu and his newly formed production house Katsu Productions were looking to kickstart a new series of chanbara films as leading vehicles for the star, as well as to keep the company functioning. For this purpose, they turned their eye towards a gekiga (Japanese version of a graphic novel) by writer Kazuo Koike, an outlandish tale of an Edo-era law enforcer. For the first one, Katsu called upon Kenji Misumi, the director with the most directing credits on the Zatoichi features, and regular cinematographer Chikashi Makiura to lend their vision to this new tale. If, however, you go into the Hanzo films expecting anything similar to Zatoichi, you're in for a very rude surprise!

Buy This Title

This is the story of Hanzo Itami, an incorruptible magistrate in the Edo period who cannot stand other officers like himself for the rampant bribery they indulge in and the injustice that comes with it. So strong is he in his resolve for justice that he refuses to sign the magisterial oath that states they do their job with dedication and honesty because of how other magistrates disregard it, in spite of him having been on the job for four years already. Hanzo is a well-known figure throughout Edo for two things: his unwavering commitment to justice and his unusually large penis. One day, while on a job catching a bad guy, he learns that a banished criminal, known only as Kanbei the Killer, has somehow escaped from captivity and has returned. Curious as to how the criminal has returned, Hanzo sets out to find out the truth but ends up discovering a conspiracy that goes far higher up than he can imagine.

Like many Ichi tales, “Hanzo the Razor” too begins with a scene of Katsu walking, this time to the oath-taking ceremony for magistrates. This scene immediately sets the entire production apart from that series and sets the tone for what to expect, with its cool editing that leaves no doubt in the audience's mind about Katsu's fully functioning eyes set to a score that sounds like something straight out of a blaxploitation film. The story, and its very dodgy morality, is no less different. Hanzo may be a morally resolute man when it comes to upholding justice, but that moral compass is easily bendable when it comes to how he goes about getting said justice, practically using his “sword” to rape women and torturing them in the throes of pleasure into confessing. This makes for an odd combination that makes Hanzo not an easy character to like, but Misumi somehow makes it work.

The feature is also a peculiar one for the exploitation genre; sure, there is violence, blood, torture, sex scenes and nudity, but not nearly enough of any of those elements to fully exploit (pun intended) the limitlessness of the genre. Thankfully, it has a clear-visioned story that sits perfectly within the genre, is engaging enough and doesn't really lose focus, at least until the final act. This final act sits so very oddly with the rest of the film, has nothing to do with the overall story and seems like an addition just to negate all the dishonourable acts Hanzo has committed in his mission leading up to that point and to paint him in a slightly better light.

The above mentioned visuals and sound are the biggest assets here. Makiura's cinematography feels way ahead of its time with some truly memorable shots that one can't shake away easily. There's a scene where Hanzo is getting a confession out of a woman and you have his purposeful face on one side, the woman's lustfully impassioned face on the other and in the background, inexplicably, a first-person view of Hanzo's member inside the woman. Makiura also makes use of some unique, inventive angles, most noticeable in the first, nudity-free sex scene to lens the more risqué moments, like the one where Hanzo thrusts himself into a rice bag. Kunihiko Murai's music also sets itself apart from the compositions that were often used in jidaegeki, making use of drums, guitars, saxophones etc to create an interesting and pleasing sound.

Those accustomed to seeing Katsu in the twenty-four Zatoichi productions that preceded the release of “Sword of Justice” must have surely been in shock and awe of his performance here, which stands in stark contrast to that character. It is, however, to the star's credit that Hanzo not only looks different to Ichi, but also walks, talks and composes himself entirely differently, feeling almost like a different actor. Ko Nishimura, a regular in a few Zatoichi adventures, plays corrupt magistrate Magobei Onishi, a role he would repeat in both the following sequels, while Yukiji Asaoka plays Omino, Kanbei's ex-lover and one recipient of Hanzo's special skills, both of who are adequately good.

As Hanzo stands with all of Edo literally laid out in front of him in the final scene, the audience is left shaking its head in disbelief over what you have exactly seen, but one cannot deny that what Katsu, Misumi and Makiura have served up is a compelling, sleazy and entertaining exploitation flick, making the prospect of watching the sequels an enticing one.