During the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s, the J-horror category became one of the most popular internationally, with films like “Ringu”, “Pulse” “Ju-on The Grudge”, “Dark Water” and more getting noticed by fans all over the world, particularly for their move away from slasher aesthetics that used to dominate the category beforehand, as much as for their rather rich context and impressive visuals. The impact continued for many years, with Hollywood picking up the rights for a number of adaptations, while many of the aforementioned titles kickstarted franchises that are still running. However, as time passed, the genre became somewhat preterit, with the plethora of titles resulting in a drop in quality that essentially deemed the genre almost obsolete.

During the latest years, however, and although too scarcely to be called a wave, or even movement, a number of new filmmakers have taken upon them to reinvigorate the genre, by including new elements in the category, in terms of visuals, context, and the overall way they handle horror. Symbolism, metaphor, intense gore and intense artistry, philosophical elements, the concept of films about films and even comedy have been implemented in that regard, with the results, as you will see by the titles mentioned below, being occasionally exceptional.

Without further ado, here are 7 films that prove that J-horror may have a future yet, in reverse chronological order.

1. New Religion (2022) by Keishi Kondo

That this film is going to be different is evident from the initial scene, when Miyabi, the protagonist of the movie, realizes that she has not paid attention to her young daughter Aoi for some time. Withοut any kind of drum rolls, both her and the audience realize that the kid has fallen of the balcony and is now dead, with Kondo moving almost immediately to some later time, where Miyabi is living in the same apartment, but with a new boyfriend, desperately trying to overcome the events of the past. At the same time, and in order to retain the lifestyle she had before she got a divorce, she works as a call girl, although considering that the story takes place in the Covid era, even that line of work is experiencing a decline. One of her workers, who seems to be rather unstable, ends up losing it completely, in a series of events that lead Miyabi taking on one of her regulars, Oka.

Oka is a rather strange man, living in an even stranger apartment, who does not want to have sex with Miyabi, just to photograph her spine. To her surprise, the photograph results in a connection with her deceased daughter, which is what brings her back and back again to Oka, who takes pictures of a different part every time. Gradually, Miyabi starts to change, to the surprise of both her boyfriend and her pimp, who become more and more worried about her, as her grip on reality seems to become thinner.

Check out the interview with the director

Channeling the dreaminess of Stanley Kubrick's “Eyes Wide Shut” and Kiyoshi Kurosawa's “slow terror” style, Keishi Kondo creates a world where everything seems to be a symbol, and reality, dream, nightmare, past and future co-exist. The result, although intensely complicated, is excellent, with Kondo creating an atmosphere of disorientation, horror, and implied/lurking violence that carries the movie for the majority of its duration, implementing all of its cinematic elements.

In that fashion, DP Sho Mishima bathes his images in intense reds, which, through an iconoclastic approach focusing on butterflies, videos on TV, photographs and a number of other elements, is one of the main ingredients of the aforementioned atmosphere. In combination with the sound and the uncannily electronic score, the movie also takes a ritualistic form on occasion, which adds even more to the horror. Kondo's own editing, which includes both flashbacks and flashforwards, results in a pace that is other times slow, other times fast, in perfect resonance with the overall aesthetics here. Truth be told, the ending could have been a bit tighter, and the regular lagging of the Japanese movie is still here, but these are just minor issues, and by no way do they harm the great sense the movie leaves.

2. Mimicry Freaks (2019) by Shugo Fujii

The story starts with a young boy with no clothes, with a chain around his arms, walking the track of an abandoned railroad. The next scene takes a leap back to the previous day, when Fuma, a man seemingly in his late twenties wakes up in a bed in a dense forest. Surprised, he finds his son standing next to him and almost attacks the boy asking him for their whereabouts. When he gets no answer, he starts running through the forest, but he is attacked by a Namahage, a Japanese folklore, demonlike being. He barely manages to escape and stumbles upon a patrol car. He asks for help frantically, but when the policeman checks his ID, he finds out that Fuma was once a convict who was executed thirty years ago.

Check out the interview with the director

At the same time, in another part of the forest, a couple who is about to get married are riding the car of the bride's father, along with their wedding planner, towards the wedding chapel the ceremony will take place. The father is not particularly happy about the wedding, since he thinks the groom is after her daughter for her money, not to mention he is totally against his anti-nuclear activism. Soon the tensions in the car rise, but a bit later the car breaks down and the four are forced to walk through the woods. Eventually, they arrive at the cabin near where Fuma and his son woke up. The meeting of the two groups is inevitable, and soon all hell breaks loose.

The narrative style could only be described as delirious, with the past and future, fantasy (myth) and reality, logic and madness continuously switching places on screen, resulting in a story quite difficult to follow. Add to that the different themes and the various “loans” from the aforementioned movies, and a plethora of scenes featuring torture, gore and violence, and you will soon realize that what you are watching could be a glimpse into the mind of a maniac.

Despite the film's promotion though, the mystery about the cloning and eugenics' experiments, the setting of the forest, the paranoid scientists-doctors and the disfigured characters point more towards a combination of “Versus” and “Horrors of Malformed Men” instead of US horror movies, although some elements of those do exist.

3. BAMY (2017) by Jun Tanaka

The introductory scene immediately sets the rather unusual tone of the film. Fumiko Tashiro is going up on an exterior elevator, when she witnesses a red umbrella flying outside the skyscraper she ascends. Some moments later, she is leaving the building and the same umbrella crashes in front of her on the street. The event alarms her and a passerby, who turns out to be an old acquaintance from college, Ryota Saeki. The story then flashes forward a year later, when the two of them are engaged, and have started living together. However, Ryota has been hiding a secret from her all this time: he has the ability to see ghosts, in a trait he does not understand and has made him somewhat neurotic. As time passes, his psychological status worsens and jeopardizes both his upcoming marriage and his work (in a warehouse). At the same time, he meets another woman with the same ability, Sae Kimura, who is even more terrified than he is. One more unexpected event complicates his life even more.

Check out the interview with the director

Jun Tanaka stated about the concept of the film: “The red thread of fate – an East Asian myth of a thread that ties destined lovers together – is nothing but a curse. We cannot will miracles to happen; they are forced upon us, abruptly and violently, by an unfathomably great power. One cannot escape it, one cannot resist it. The mythical thread then, if it exists, is surely something monstrous. Faced with such a force, man is always small and powerless. This miracle picks its targets arbitrarily, toys with them, and will not relent until its thread has drawn the fated pair together.”

This point is represented, visually, by the almost omnipresent red umbrella, who symbolizes the above red thread, the connection between Fumiko and Ryota, which seems impossible to be cut. The presence of ghosts represents the second point; about the lack of control people have over their fate, and in essence, their lives. In that fashion, Tanaka communicates a rather pessimistic comment, which has people as puppets of fate, with little or none authority upon it. While the message is significant, the relationship of the two protagonists do not justify such a strong connection, since it seems like a usual, even uninteresting one, where the woman has the dominant role of the boss-mother and the man the one of the absent-minded man-child. Furthermore, the highly surrealistic ending sequence makes the message even more confusing and abstract, as the supernatural seems to give its place to the fantastic.

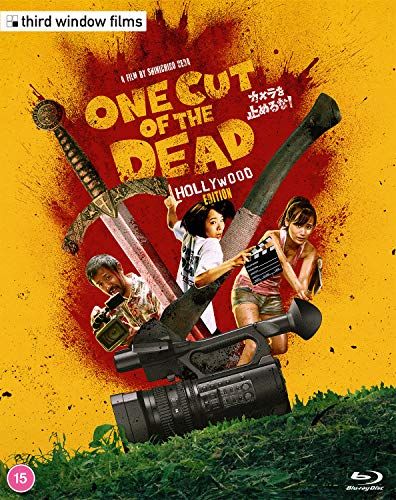

4. One Cut of The Dead (2017) by Shinichiro Ueda

Attempting to film a new zombie movie, maverick director Takeyuki Higurashi (Takayuki Hamatsu) grows frustrated by the overall lack of professionalism in his cast and storms off, leaving his wife Nao, (Harumi Syuhama) to calm the others down. Shortly thereafter, a series of strange attacks by a group of deranged and savage killers occur, which is soon revealed to be the end result of the film shoot. Traveling back to reveal the process of how the whole shoot turned out and how the zombie apocalypse began, which soon forces the crew into fighting the zombie apocalypse for real.

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

This was an enjoyable and intriguing effort. Among the many impressive elements is the manner in which ‘One Cut' pulls off the engaging social commentary about the effects of filmmaking. This really brings up the idea of what constitutes entertainment as the executives are constantly shouting out about what they expect and demand on a live-shoot. The backstage exploits, filled with egotistical actors stuck in roles they don't want, stressed-out stage-hands and the on-the-fly guerrilla tactics that must be employed to ensure the shoot goes off smoothly, feature prominently throughout the second half. There are some fun times ahead, commenting on the rushed nature of filmmaking and how creative individuals must sacrifice their vision to make content for disillusioned executives who only care about the profit lines.

As well, the most engaging aspect here is the utterly enjoyable opening sequence. Consisting of a single-take short-length scene featuring the crew being attacked by a zombie outbreak before turning on each other and then chasing each other throughout the complex where they're shooting. Managing to throw plenty of twists and turns amongst the gory action, all done in one single unbroken take, gives this a wholly unexpected opening that's a real attention-grabber. As the second half of the movie is the filming of this very sequence which is full of hilarious antics and ingenious fixes to demonstrate how the actual shot got pulled off. It's quite ingenious to see how the different tricks to accomplish the finished product and the different tricks accomplished to get there. This aspect manages to hold the movie up as quite enjoyable in these different sections. It gives a chance to show off the make-up effects by Kazuhide Simohata and Jyunko Hirabayashi in both the one-take sequence and the behind-the-scenes footage. (Don Anelli)

5. The Eye's Dream (2016) by Hisayasu Sato

Maya, the protagonist of the film is quite a character. She was abducted and raped when she was a child by a man who removed one of her eyes, forcing her to replace it with a fake one, and at the same time, making her obsessed with eyes. Currently, Maya is a photographer who uses a very aggressive technique: she actually hunts people in the streets, shoving her camera in their faces, in order to photograph their eyes from as close as possible. She exhibits the photos she acquires in a warehouse filled with every kind of digital and analogue medium, including videos, screens and framed photos, all of which depict eyes in disturbing fashion. Her girlfriend, Rie is responsible for this techno-industrial setting.

Eventually, Maya meets a neurologist named Sata, who diagnoses her with an unusual form of phantom pain, the result of her kidnapping. He also asks her to allow him to shoot a film about her, in an endeavor that includes his assistant, Yuichi, following her with a camera as she photographs people. At the same time, a maniac who attacks people and takes their eyes roams the city, and Maya's former tormentor has not forgotten her.

Hisayasu Sato directs a paranoid film where the borders between fantasy and reality are very thin, and is filled with abnormal eroticism and sadism, that seems to draw much from George Battaille's “Story of the Eye,” as, for example, regarding the use of eye bulbs during the sex scenes. Apart from that, the film is filled with lengthy, steamy, and occasionally abnormal sex scenes and gore, which is usually turned towards people's eyes, not to mention phrases like “Raping you was so spectacular” and “Let me lick your eyeball.”

However, the film is not all gore and sex. Sato makes a distinct comment about the way people perceive the world through their eyes, in a tendency that is frequently misguided, and presents voyeurism in a very extreme fashion, through the concept of Maya's way of taking photos. In that fashion, the film lingers somewhere between the grotesque and the psychedelic, with the production values heightening this sense even. Miki Shigenori's cinematography is impressive, as he creates a hellish world filled with grotesque close ups, fluorescent lights, meaningful shadows and digital images, similar to the style implemented in Shinya Tsukamoto's “Snake of June.” In combination with Castaing-Taylor's frequently abrupt, but always quick editing, the film occasionally functions as an extreme, but visually impressive music video.

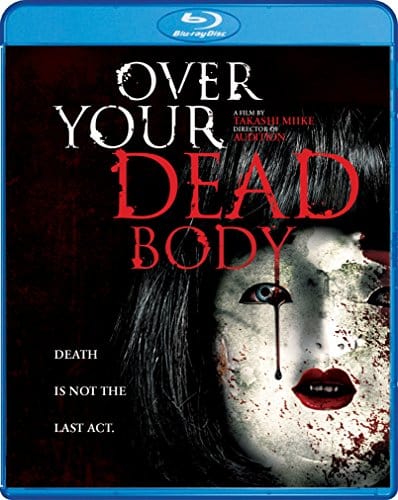

6. Over Your Dead Body (2014) by Takashi Miike

The film follows a theatre troupe as they rehearse a play where a samurai seduces a woman and then murders her disapproving father, in order to inherit his estate. However, when he is offered the granddaughter of another wealthy man, his true colors are disclosed to his wife, who eventually returns as a ghost to hunt him. In actual life within the movie, the female star of the film named Miyuki Goto has pulled some strings to give the main protagonist role to her boyfriend, Kosuke Hasegawa. However, as other actresses Rio Asahina and Jun Suzuki lust after Kosuke, their lives begin to mirror those of the play, as the lines between fiction and reality gradually disappear.

Takashi Miike directs a horror film that moves on two axes. The first is the actual life of the actors, including the intrigues among them in the rehearsals, and the second is the actual play, with the borders between the two becoming blurry after a while. The horror element is subtle in the beginning, but as the film progresses, it takes its ual place in Miike's pictures, with a number of grotesque scenes (including one which is very difficult to watch, regarding a woman performing an abortion on her own) and bloodbaths.

Horror though is usually achieved in films through sound, and “Over Your Dead Body” is a film that excels in that aspect, with the various sound effects making more horrific even the most violent scenes. Nobuyasu Kita.s cinematography is quite polished and dominated by dark and grey shades, that at moments reminded me of Tetsuya Nakashima's “Confessions,” in a rare tactic among the latest Miike's productions, which are usually filled with color. Kenji Yamashita's editing is also artful, maintaining the balance between the two “worlds” in a fashion that can be easily understood by the spectator, despite the constant mixture of fantasy and reality.

Miike's entertaining “eccentricity” could not be missing, and is chiefly represented by a limp actress and the constant crying of a baby, both of which intensify the eerie atmosphere that permeates the movie. Furthermore, the casting of a kabuki actor in the role of a theatre actor is a notion that could only occur in Miike's mind. Lastly, and in an unusual tactic for the contemporary Japanese cinema, there are many sex scenes present, with the first one even appearing in the very beginning.

7. My Mother's Eyes (2023) by Takeshi Kushida

Takeshi Kushida directs a psycho thriller essentially, and the narrative will remind many of Kim Ki-young's films, although the sexual connotations are substituted by a mother-daughter relationship (and eventually a father-son one). The codependence that can frequently dominate this type of connections is implemented in extremes here, with the concept of the VR goggles essentially making the two women, one. And while the mother always seemed to want that, to create a daughter based on her own self, the way the daughter also starts to enjoy the concept, also because it is her only way out from the constant watching of the ceiling (as mentioned in the movie), definitely moves into the area of perversion. Especially since sex, violence, and in general, any experience the mother has, so does her daughter, as the two become more and more as one.

Where can these films be seen. I can’t seem to find any options online.

There are Amazon links included when available. For the rest, we will have to wait I guess