“Two Blue Stripes” is the directorial debut of the Indonesian screenwriter and entrepreneur Ginatri S. Noer. A commercial success in its native country, this movie about an Indonesian teen couple's pregnancy has won awards at the 2019 Bandung Film Festival and the 2019 Indonesian Film Festival.

“Two Blue Stripes” is Screening as Part of Asian Pop-up Cinema Season 12

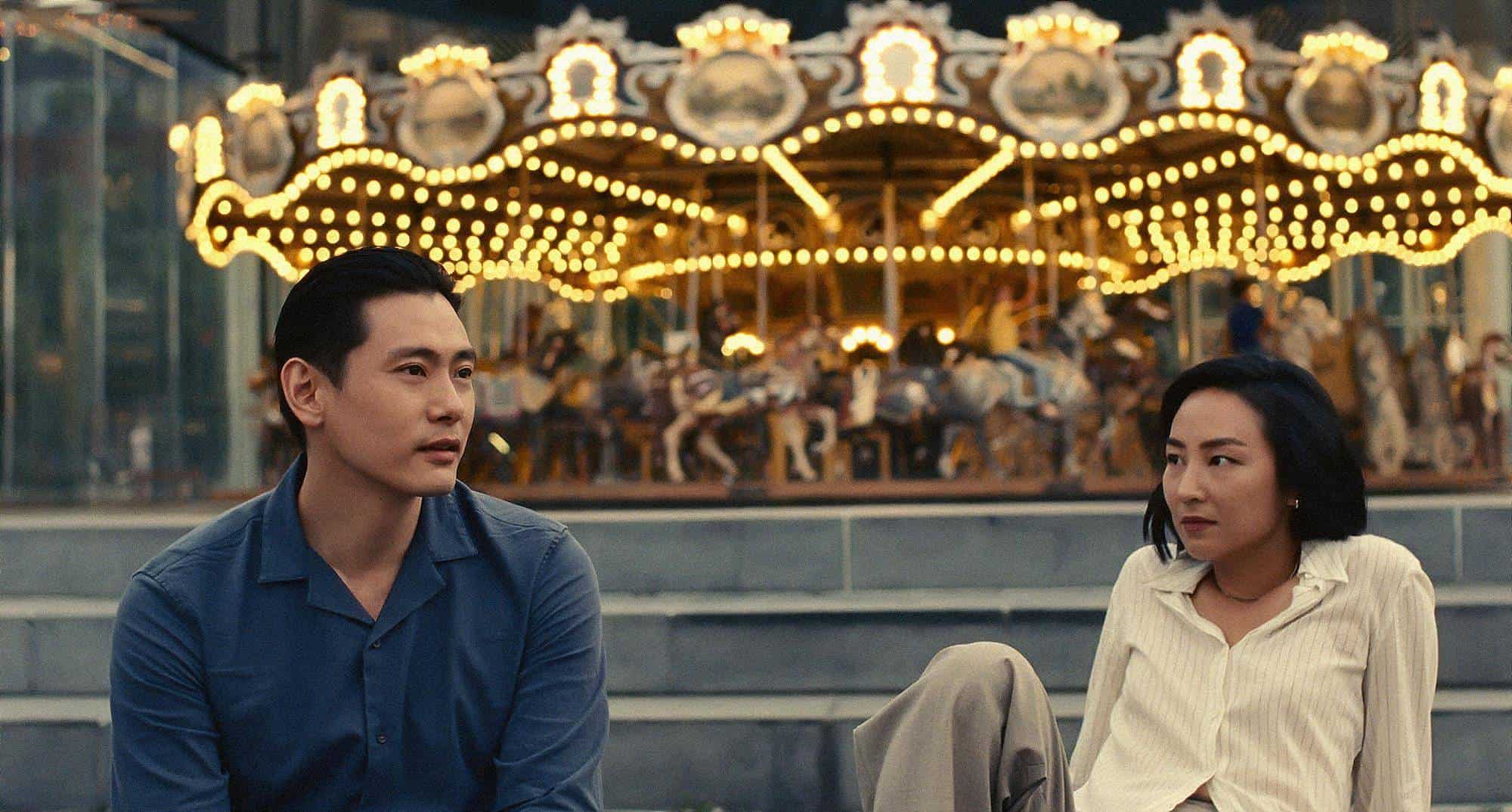

Though the polar opposites, both economically and academically, Bima (Angga Yunanda) and Dara (Adhisty Zara, ex-JKT-48) are a high school couple. One day, while fooling around alone in Dara's house, one thing leads to another and Dara ends up pregnant. Shocked by what's happened, Bima tries to run away and convince his girlfriend to have an abortion, but later realizesthe weight of his deed and decides to take responsibility and help Dara hide her pregnancy and finish school. Soon, the girl's pregnancy is discovered and the couple has to bear the consequences of their actions – Dara has to quit school to tend to her pregnancy while Bima, a much worse student than his girlfriend, is forced to continue attending a school he does not want to go to, work at Dara's parents' restaurant, grow up and prepare for the birth of his child.

Everyone who only encounters the plot synopsis might erroneously take “Two Blue Stripes” as a cheesy and preachy teen movie. And they might not be that far off, the film has a lot more depth of observation to give the attentive and open-minded viewer than initially anticipated. Let's take Bima and Dara's relationship as an example. He is a poor and bad student, and she is a rich and good one, something we've seen numerous times in other films, and is, on first sight, rather cliched. Yet, through it, Noer manages to make prescient observations about contemporary neoliberal society and its inherent lack of fairness. Dara's bright future comes not only from the fact that she is smart (something which we might take, again, as a result of her parents' high social position) but also from the fact that she does not have to worry about anything and can think of life as full of opportunities. Something which the poor Bima who has to help his parents, simply is not afforded.

At times, it is even a direct critique of the lack of sex education at school. The teenagers know nothing about it apart from a scant poster in the infirmary and maybe some basic education at school. Thus, the teenager's pregnancy, something that happens a lot in Indonesia, is less of her or Bima's fault than that of the education system and government at large. Instead of castigating young couples for things they will anyway do, the government should educate them properly. Noer's debut is also a critique of the school system which not only does not take responsibility for the fact that it doesn't educate its students properly, but also punishes them for its own failures. This we see through the fact that Dara is strongly advised (i.e. forced) to quit school so as to not hurt its image, showing it less of a place for education of the youth than a business.

This brings us to one of the most interesting aspects of the movie's observations (I can't go as far as to call it critique) of contemporary society – the topos of East Asia, namely Korea and Japan. From very early on, Dara's desire to go to Korea is firmly established. Like all modern southeast Asian youth, she sees the country as a place of endless possibility and even reinvention. Something like another USA. She dreams of going there after finishing edging school and even practices hard to learn the language. Bima, on the other hand, seems not to understand the possibility inherent in moving to Korea, he sees only the K-Pop idols that adorn Dara's walls. For him, the country is only a place of fake people and feminine idols. Even more, as it is very briefly mentioned in the beginning, he is a person who is rather behind the times. And how is this done? through his use of Japanese. We see this in the beginning when she tells him she loves him in Korean and he replies in Japanese. It is an incredibly brief scene but it tells the world of difference between the two of them – he is set in the past, both culturally and ethically, while she belongs to the present. Which one is better, though, is slightly ambiguous.

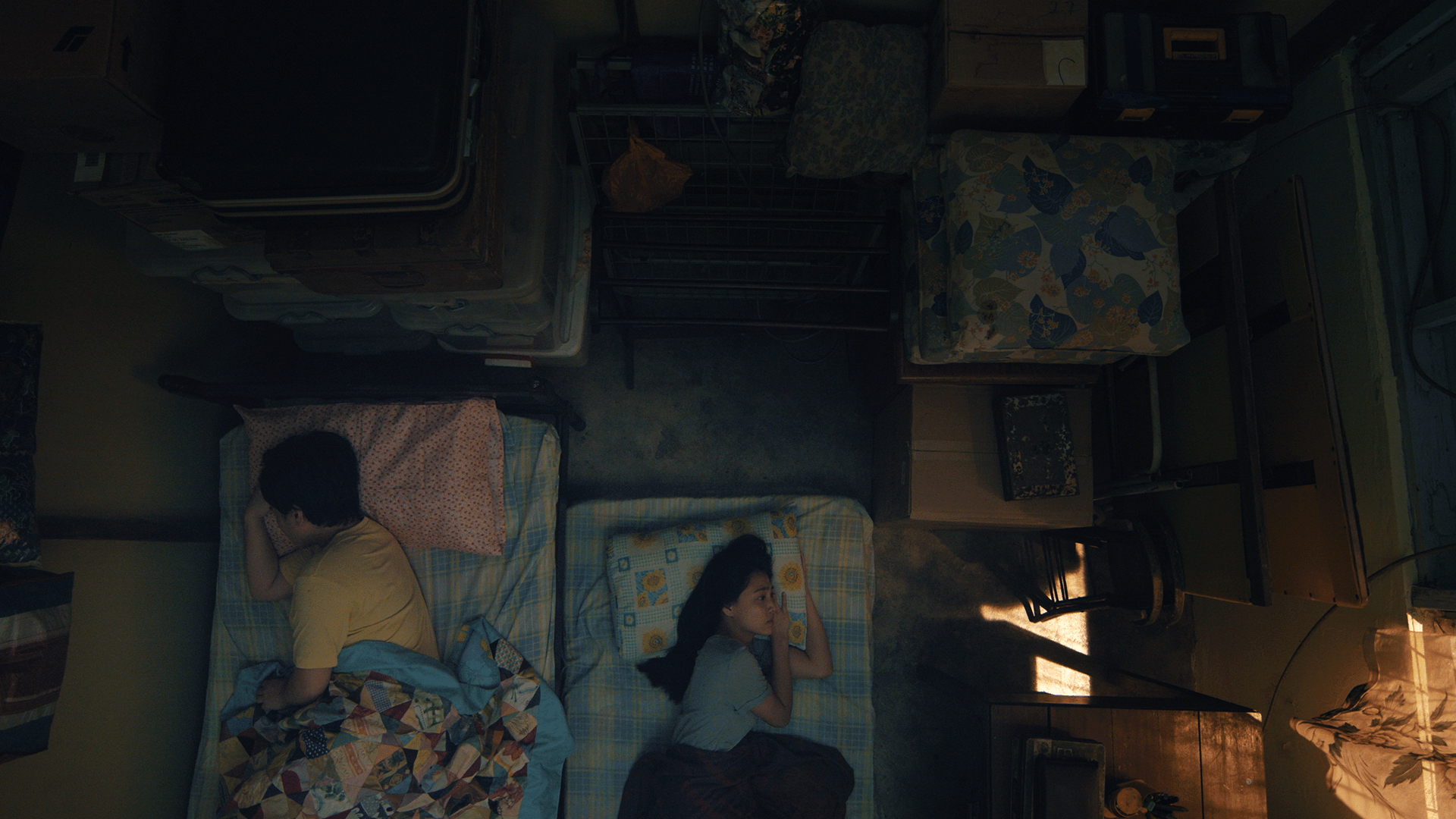

Ginatri Noer shows the difference between the teenagers' social status through the entire film but the most striking is the scene of Dara visiting Bima's house for the first time. She does not go there voluntarily, but is somewhat forced by the circumstances, because her parents are mad at her for getting pregnant by a poor boy and ruining her future. We follow her entering Bima's house in what must be the movie's longest shot. The camera slowly follows her walking down narrow cavernous roads in a manner that reminds us of a descend into another world, one that she did not even imagine existed. Yet, it abstains from any judgement, both of the “sullied” girl and the poor parents. However, this has somewhat nationalistic undercurrents as it juxtaposes Bima and his traditional Muslim parents as ethical and caring people to Dara and her Westernised parents, and especially her mother, who are shown as individualistic and shallow. This together with the very confusing and at times questionable ending leaves the viewer with a somewhat bad taste in their mouth. Even so, the “Two Blue Stripes” is an interesting, humane and immensely watchable coming-of-age story.