11. Flame in the Valley (Kim Soo-yong, 1967)

Kim Soo-yong takes the myth of Lysistrata and adapts it to a Korean setting, in order to present a multi-level anti-war theme and a number of social comments. The blight of war, particularly regarding the ones left behind is the most obvious one, with the basis of the film formed on the fact that women have to take over all the responsibilities men had, just in order to survive. Kim seems to mock the concept of the two Koreas, metaphorically, through the two main protagonists, who live across a narrow “street” but are in essence enemies, due to the civil war. The fact that what makes them come together eventually, is the longing for a man, and in essence, sex, also moves in the same, mocking path, as it also highlights the fact that, despite the side picked, the two characters are, in essence, the same, as is the case regarding North and South Koreans (at least at the time). (Panos Kotzathanasis)

12. Woman of Fire (Kim Ki-young, 1971)

Kim Ki-young uses the theme of the “femme fatale entering a quiet home to bring things upside down” in order to present his psychosexual comments, mostly through their consequences. The fact that Myeong-ja has a fit during the attack she suffered in her hometown, which continues to occur every time she witnesses others having sex, is a testament to this tendency. For Kim, sex seems to be a power with psychosomatic effects, as we watch Myeong-ja's sex-driven, downward spiral towards paranoia that seems to draw down both her “masters”, along with her. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

13. Insect Woman (Kim Ki-young, 1972)

The erotic element, however, is characterized by a unique cinematic approach, with Kim Ki-young and DP Jung Il-sung using a number of artistic approaches towards those scenes. Kaleidoscopic and microscopic sequences are juxtaposed with extreme zoom ins and neon lights, while the use of psychedelic rock and funky tunes intensify this approach even more, without, however, stripping away from the sensuality of those scenes at all. Particularly the scene on top of a glass surface filled with colored candy is a marvel to watch, and an iconic one for Korean cinema. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

14. The Road to Sampo (Lee Man-hee, 1975)

Lee Man-hee-I highlights the fact that he feels affection for his characters, since despite the fact that they are all “losers”, he takes care of showing that powers beyond them have left them in the circumstances they are now. Through this concept, the film is permeated by a rather eloquent melodramatic tone that functions as a comment about the consequences of modernization, particularly on those who did not “catch the train” of progress. This aspect is highlighted in the film's finale, while the fate of Baek-hwa and Yeong-dal's relationship also moves towards this direction. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

15. The March of Fools (Ha Gil-jong, 1975)

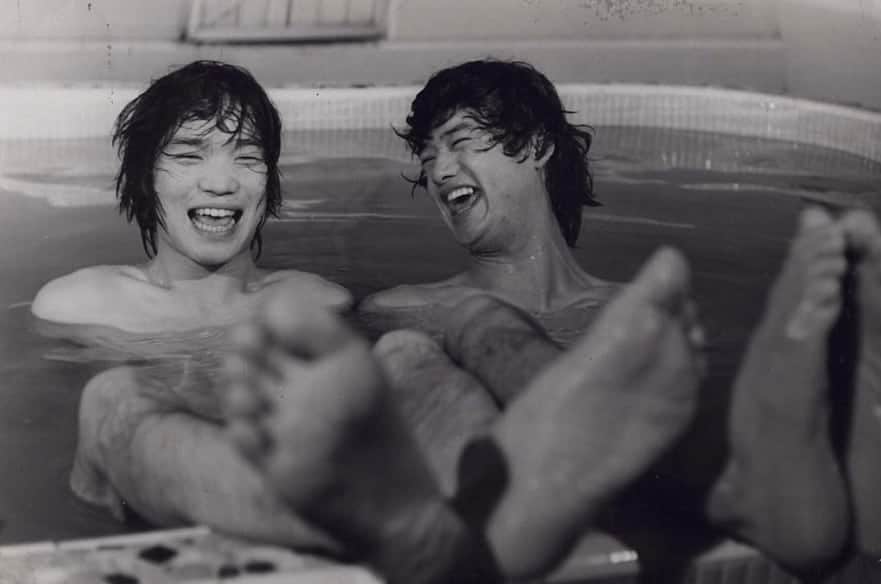

Like a lot of Ha Gil-jong's films, in particularly the two films that preceded this one, “The March of Fools” is filled with a lot of angst, in spite of it being a light-hearted film for the most part. This angst in his films was fuelled by him having witnessed civil revolutions and unrest both in South Korea and United States, where he went to study filmmaking, while he was still in his twenties. In “The March of Fools”, this is directed towards the authoritarian state of the time that put restrictions on everything; from the haircuts the men could have, evening curfew times to even classes in schools and colleges, which could be shut down indefinitely at any time without prior notice. Free thinking wasn't welcomed, nor was the “westernisation” of thoughts and people's attitudes. Ironically, this only went on to be more pronounced with the censors' efforts to suppress the film. (Rhythm Zaveri)

16. Io Island (Kim Ki-young, 1977)

Kim focuses on portraying the clash between the modern and the traditional, the money-driven capitalism and the superstition-filled folklore, with the various stories repeatedly highlighting who the winner is, in dramatic fashion. The central theme of the film, though, seems to revolve around propagation, a concept that is mainly depicted through Seon Woo-hyeon's story, with it actually shaping his whole life, both in social and professional terms. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

17. The Last Witness (Lee Doo-Yong, 1980)

Ji-hye, the daughter of an army captain, receives a treasure map from her father just hours before he is killed by communist guerillas in the mountains near their home. While the communists are defeated, several escape the battle and begin a quest to track down the map and make its secrets their own.

18. A Fine, Windy Day (Lee Jang-ho, 1980)

The various struggles of the three friends, and occasionally of those around them form the main element of the narrative, with Lee Chang-ho presenting their struggles through a very entertaining combination of comedy and drama, which carries the film for the whole of its 113 minutes. However, underneath the amusement, Lee has managed to present a rather harsh critique of both society and the government of the time, as the three protagonists seem to struggle against both. Perhaps the most obvious metaphor, as much as his message of hope, is presented near the finale, when Deok-bae, who has taken up boxing, is fighting in a ring with a much bigger man, whose clothes spell Korea with big letters on them. Deok-bae tries to fight back, but is repeatedly knocked down and ends up in blood. He keeps fighting though, and despite the fact that he is completely beaten, he seems happy. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

19. People in the Slum (Bae Chang-ho, 1982)

Bae Chang-ho presents a multilayered script that works on a number of levels. Through the flashbacks, he presents the romantic but tragic past story of Myeong-sook and Joon-il, and the reasons that led her to become a couple with Tae-seop. The impact of growing up in a house where love is not easy to be found is examined through Joon-il and his “extreme” behaviour. The concept of crime and punishment is examined through the life stories of both Tae-seop and Joo-seok, who also “serve” as samples of the concept of manhood, an idea that is presented in all its proud, but also illogical glory. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

20. Village of Haze (Im Kwon-taek, 1982)

Im Kwon-taek does a splendid job of commenting on human nature, and particularly the roads it is led in extreme environments, as the secluded village in the story. His most obvious comment can be summarized by the phrase “extreme conditions demand extreme measures” but this is just the tip of the iceberg, as the comments extend to much more than that. The need for sexual comfort and the non-monogamous nature of people is another central one, with Im though, not failing to show the consequences, through a number of rather violent scenes in the film. (Panos Kotzathanasis)