To fully understand and appreciate the place of importance that Ha Gil-jong's “The March of Fools” holds in the history of Korean cinema, one needs to understand the tumultuous journey the film had. From the first draft of the script, written by celebrated and oft-adapted novelist Choi In-ho from his namesake novel, to the multiple revised resubmissions of the script, from notifications received while shooting to the submitted first trailer and even the final print, the film was hounded by the strict censorship at the time, which set to completely change the writing of Choi In-ho and the vision of Ha Gil-jong by removing anything that showed the Korea of the time in a bad light. So what was it about the film that had the censors so vexed?

“The March of Fools” is screening at London Korean Film Festival

The film begins with a group of underwear-clad youths being taken through various physical examinations for acceptance into compulsory military service. Amongst the group are best friends Byung-tae and Young-cheol, two spirited philosophy students full of life and dreams. While Byung-tae passes the examination with flying colours, Young-cheol, who develops a stammer when nervous, fails in almost every examination. Shortly after, one of their classmates announces the sale of tokens for an arranged blind date session with girls from the nearby women's university that he has arranged.

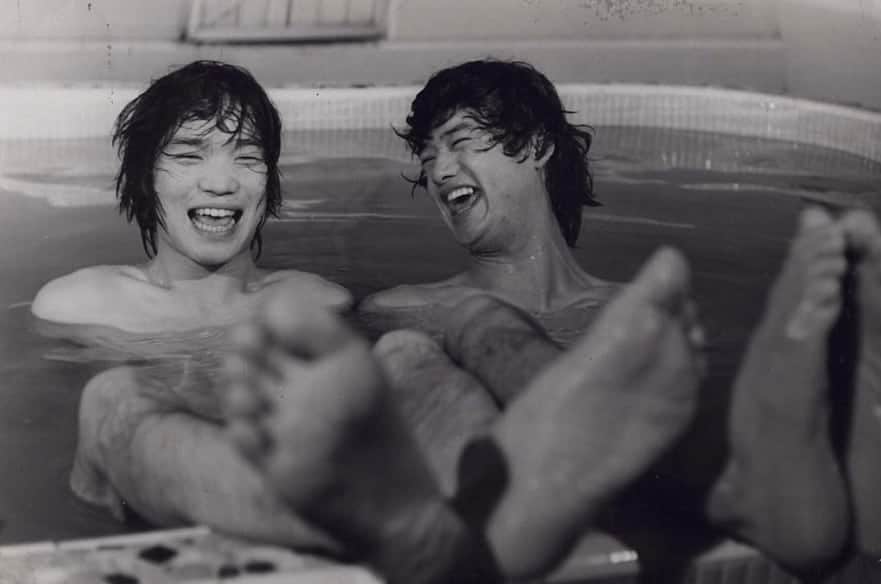

The two boys get unlucky numbers 13 and 4 respectively and following a run-in with the law for their long hair, they arrive belatedly for their blind dates where Byung-tae meets Young-ja, a flirtatious girl who knows exactly what she wants in life and how to get it, and Young-cheol meets Soon-ja, who seems disinterested in him. The film then follows the two friends as they enter drinking contests, play soccer and hang out in pool parlours while they suffer from love and heartbreak, dream and hope, even as their dreams and hopes amount to nothing in a society oppressed by a strict military regime.

Like a lot of Ha Gil-jong's films, in particularly the two films that preceded this one, “The March of Fools” is filled with a lot of angst, in spite of it being a light-hearted film for the most part. This angst in his films was fuelled by him having witnessed civil revolutions and unrest both in South Korea and United States, where he went to study filmmaking, while he was still in his twenties. In “The March of Fools”, this is directed towards the authoritarian state of the time that put restrictions on everything; from the haircuts the men could have, evening curfew times to even classes in schools and colleges, which could be shut down indefinitely at any time without prior notice. Free thinking wasn't welcomed, nor was the “westernisation” of thoughts and people's attitudes. Ironically, this only went on to be more pronounced with the censors' efforts to suppress the film.

What “The March of Fools” excels at is putting the viewers square in that era of dreams, uncertainty and fear, as the two boys go about finding what normalcy they can, going about dating and drinking, bemoaning what's wrong with society and discussing their hopes and dreams, which hold very little meaning and exist mainly to remain unfulfilled in their suppressed existence. In a scene where Byung-tae and Young-ja are enjoying a quiet evening in the garden, the reference to Richard Bach's novella “Jonathan Livingston Seagull”, about a seagull's dream to fly high, fits the film's themes and era well.

This time capsule-like quality of the film is further enhanced by Jung Il-sung's cinematography, which captures the mood of the era well. Some of the shots which involve the police, with their dizzying camera movements, when compared to the otherwise “calmer” shots, are noteworthy. Equally impressive are the last two bittersweet scenes of the film, the tragic penultimate one with its stunning panoramic shots and the final scene which includes arguably the greatest final shot in Korean cinema, both of which would not have existed had the censors had their way with the film. The editing of the film by Hyun Dong-chun does seem jittery at times, but that is more due to the incessant intervention of the censors than anything else, which rendered several scenes and set-ups of the director completely useless. This is most noticeable in the scene where the two boys exit a police station after having been bailed out by Young-cheol's father, with no predecessor to explain how they got in that situation in the first place. Kang Keun-shik's music includes original songs and compositions which fit the film's energy and mood well.

The four key actors, all fresh faces at the time, do well with the comedic as well as the emotional parts in their respective roles. Yoon Moon-seop as Byung-tae and Ha Jae-young are particularly well cast and their broad-smiled, hopeful faces do well to hide the oceans of worry in their eyes. While Kim Young-sook doesn't get too much scope as Soon-ja because of her limited screentime, the twinkly-eyed Lee Young-ok is a joy to watch as the vivacious Young-ja.

Despite all the censor issues, Ha Gil-jong was able to finish and release the film, which eventually became the second highest-grossing one of the year. He went on to make films that were equally popular and well received in his short career and short life, but “The March of Fools” remains his most accomplished and revered work. Interestingly, Ha himself wasn't very pleased with the final output, claiming he just finished the film to make Choi In-ho some money. The film, however, today stands as Ha's most representative work and rightly enjoys the status of a classic and a masterpiece of Korean cinema.