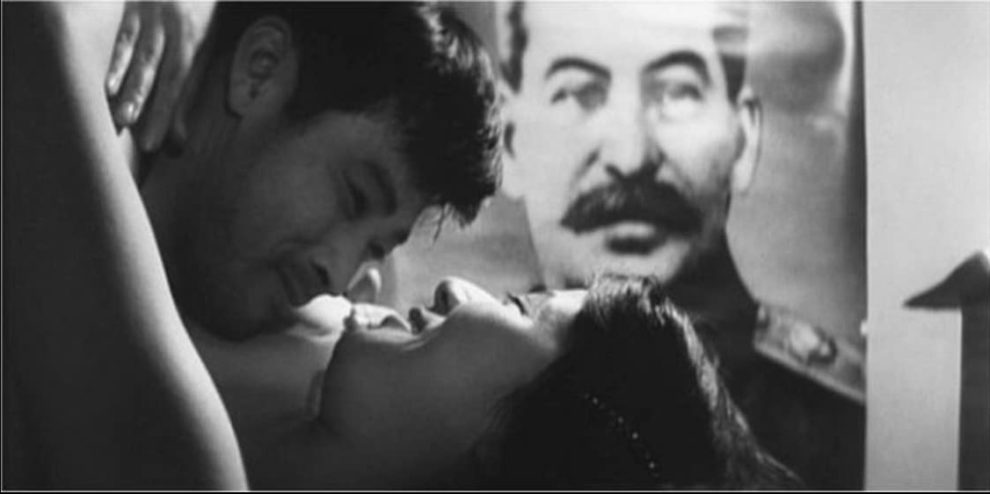

As was the case with many of Wakamatsu's works, “Secrets Behind the Wall” was surrounded by intense controversy. Being the first release of his own production company, Wakamatsu Pro, it was backed financially by Kokuei, whose people though, received a completely different script than what the cunning director ended up with, in a rather risky move, which paid off completely though. The movie was a commercial success and became one of the first pinku films to screen outside of Japan, on the 15th Berlinale. However, the Japanese authorities, the majority of the critics and in general a number of people who watched the movie reacted quite intently, particularly due to the introductory scene, where a woman has sex with a communist man, who carries an atrocious scar caused by the atomic bombing, with the whole scene taking place under the portrait of Stalin. Even more so, she mutters to him, “You are an emblem of Hiroshima, an emblem of Japan, an anti-war emblem”, something that scandalized the Japanese even more due to the irony involved, as much as for exposing things the majority wanted to forget. Furthermore, the authorities were outraged that, only a year after the Olympic games, and also only a year after Japanese citizens were permitted to fly outside of the country since the end of war, a man whom they considered as a pornographic director with a gangster background received an open ticket to fly to Germany.

Many critics called “Secrets Behind the Walls” a national disgrace, while the industry also threw a fit, since this was the film that was to represent the country internationally, and not any from the major studios that have also submitted their productions to Berlinale. Expectedly, and in one of the earliest samples of his abilities as a “salesman”, Wakamatsu took advantage of all the hype to achieve commercial success, as we mentioned before (source: Jasper Sharp, “Behind the Pink Curtain”).

The film focuses on a number of people living in an apartment building, all of which seem normal on the first look (with the exception of the aforementioned couple of course), but are revealed as anything but as the story progresses. The main protagonists are a family of four, where the wife and husband frequently argue about sociopolitical issues, and particularly how earning money eventually becomes a concept that turns against the community and the family. The son supposedly reads intently for his exams, frequently flaunting his supposed angst as a means to get anything he wants, a behaviour that his sister, who has her own “adventures” to deal with, cannot stand at all. However, what the young man does in reality is to read porn magazines and to peep through his telescope on the housewife across having an adulterous affair

His sexual frustration is palpable, and the fact that their tiny apartment has him listening to his parents when they are having sex does not help at all. Eventually, he erupts, and his first victim is his sister.

Wakamatsu directs a film that set the tone for the rest of his independent work, with Adachi filling the narrative with sociopolitical dialogue, which “interrupts” the many scenes of sex and violence. Through this approach, the two filmmakers highlight how spent the Japanese family is, as every protagonist is portrayed as suffering from sexual frustration and some sort of depression. The style occasionally seems as mocking the Ozu-esque concept of family, as the domestic drama here takes a rather exploitative turn.

That the protagonists are essentially housewives adds to the whole aesthetics, as these are the women that are usually considered as being the measure of “normality”. In this case, however, they are presented as having sex in their mind much more than house chores, or other, ridiculous notions, as the middle-aged neighbor who throws her underwear to other balconies on purpose, to show off the fact that they are French-imported. At the same time, their failure as parents, a concept that is dominating Japanese family dramas nowadays, is also depicted eloquently, through their interactions with their children, and the impact their behaviour has on theirs.

The last part of the story, when the son completely loses it, goes a step even beyond, essentially presenting the domestic setting, which Japan presented as one of complete harmony and happiness and the main source behind the rapid financial progress the country experienced at the time, as one that can push the new generation to madness. Expectedly, this part is presented in rather extreme fashion, involving incest, but this is not much different than what Takashi Miike did in “Visitor Q” for example, making social commentary through exploitation elements.

Masayoshi Nogami gives a great performance as the son, with his gradual transformation being one of the best assets of the movie, as much as his evident (to the audience at least) perversion. Hideo Ito's cinematography, adds to the overall sense of perversion through intense close-ups and the voyeuristic view of the telescope, while the claustrophobic way he has shot the apartment highlights that the buildings function as a mental prison.

“Secrets Behind the Wall” is a difficult movie to watch, particularly for the introductory scene and the finale, but through its exploitative portrait of family life, manages to emerge as rather realistic, even if the effort to shock and scandalize is equally evident.