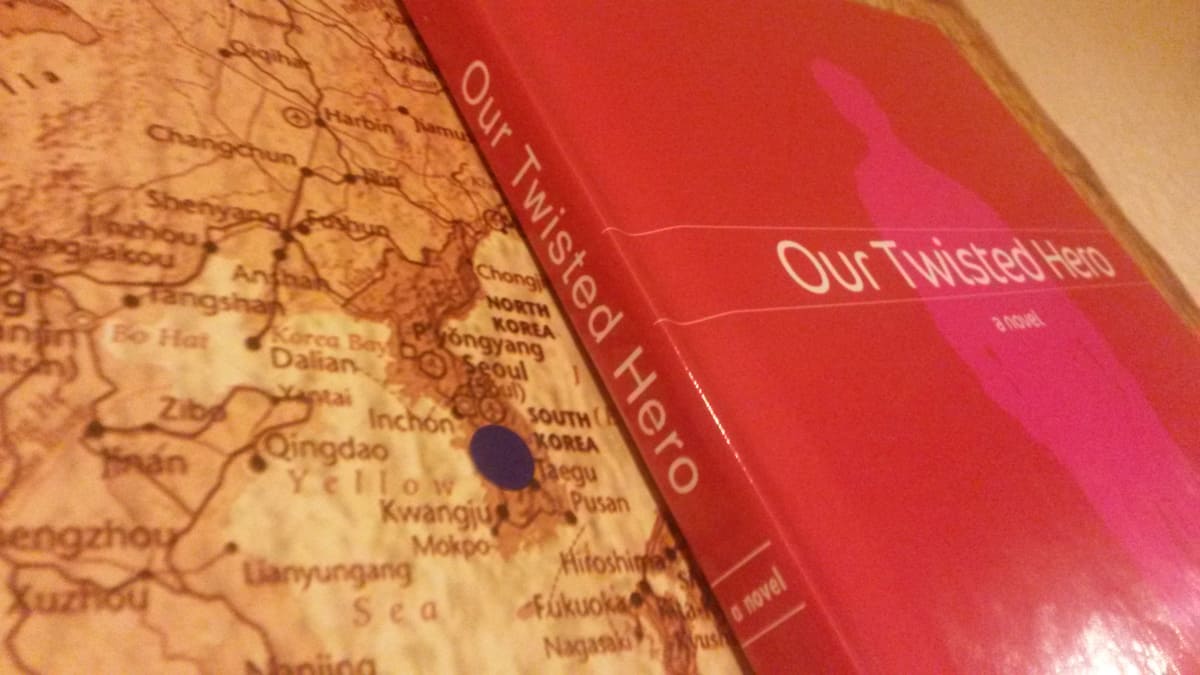

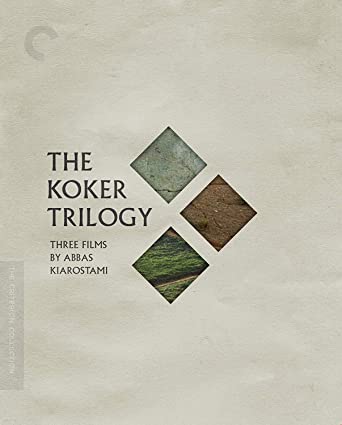

While international critics and cinephiles alike were celebrating features such “Close-Up” and “The Taste of Cherry”, making a movie in his home country became increasingly difficult for director Abbas Kiarostami. Luckily, he would find financial backing in countries such as France, which was also the case for his 1999 feature “The Wind Will Carry Us”, whose title refers to a poem by Iranian author Farough Forrochzad, an artist Kiarostami cherished a lot, considering one of the main characters in the movie recites the poet's work on various occasions. “The Wind Will Carry Us” manifested its director's reputation internationally, winning the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the FIPRESCI Prize and various other awards, with many people calling it one of Kiarostami's best works.

In order to document a rare burial ceremony, four men from Tehran travel all the way to the remote village of Siah Dareh, disguising themselves as engineers, not to raise any suspicions among the locals. Whereas his colleagues mostly stay in bed or within the vicinity of the place where they have found accommodation, Behzad (Behzad Dorani) explores the village and its surrounding area, trying to get in touch with the villagers. However, apart from a boy who becomes his guide, he is unable to connect to other people and thus, has to rely solely on the contradicting bits of information he manages to receive about an old woman's state of health. At the same time, he spends his days gathering various supplies, milk, bread and water, for his colleagues, as well as driving back and forth between the village and a grassy hill where his cell phone has the best coverage.

Eventually, a trip which was meant to be only for two or three days, goes on for quite some time, with no sign of the burial rites or the ceremony ever taking place. Apart from his colleagues, Behzad's family and publisher back in Tehran also become frustrated with the lack of progress, but still he maintains it will only be a few more days. More importantly, Behzad has finally connected with some of the other villagers and learned to appreciate the countryside, making the idea of leaving somewhat incomprehensible.

Although many consider “The Wind Willy Carry Us” Kiarostami's most poetic and beautiful feature, it is perhaps one of his most experimental movies as well, utilizing elements of the absurd to tell its story. Similar to the protagonists of Samuel Beckett's “Waiting for Godot”, Behzad and his colleagues also wait for en event which may or may nor happen, and about which they receive contradicting, at times even misleading information. Ironically, it is life itself that thwarts the plans of the characters time and time again, as the health of the sick woman, if the boy's statements can be believed, improves or worsens, seemingly within hours. As the viewer, along with the main character, becomes used to the everyday routine and the uneventfulness, the village itself, and especially its surrounding landscape, begin to transform, mirroring the change in perspective within Behzad.

Apart from the landscape and its transformation, highlighted by Mahmoud Kalari's cinematography and use of natural light, the concept of repetition plays a vital role within the narrative. Each day in the village follows a similar pattern for the main character, with most of his chores interrupted by calls which make it necessary for him to travel to the aforementioned hill. For the viewer, as well as for Behzad, these become increasingly more annoying, not just for the journey he has to go through, but because they disrupt the connection to this landscape and its inhabitants. It seems as if Kiarostami utilizes the concept of deceleration, similar to his approach in “The Taste of Cherry”, to highlight the kind of beauty and peace we must learn to appreciate more.

In the end, “The Wind Willy Carry Us” is another poetic drama about life, beauty and our perception of it by one of cinema's most gifted storytellers. Its is a truly magnificent feature, essentially about learning to see more within our world, and appreciate all the details.