During the last few days, and on the occasion of our tribute to Hong Kong New Wave, there have been a number of discussions on Facebook (link 1, link 2) regarding what is, and more intently, how long the particular wave lasted. Our interpretation of the wave was based on Pak Tong Cheuk's Hong Kong New Wave Cinema (1978-2000) , the definition Wikipedia gives, and two articles from movementsinfilm.com (link 1, link 2). However, a number of experts disagree with this opinion. We asked a number of them to share their opinion.

Arnaud Lanuque

For me, the HK New Wave starts in 1978 with the Extra and ends up around 1984 (with most of the filmmakers from the movement being absorbed by big studios). But, as you said yourself, it's certainly open to debate and I know some have a more restrictive time frame of 1979/1982. To answer your question about the second wave, I would date it from 1984 (first films of Stanley Kwan and Mabel Cheung) to 1990. But, once again, opened to debate and probably even more than for the New Wave, as the Second Wave is even looser in its definition

Kevin Ma

I would not agree with Cheuk Pak Tong's assessment of how he dates the New Wave. Having been his student in film school, I also don't remember him dating the New Wave up to the 2000s in his classes, either.Most local film people here in Hong Kong would limit the Hong Kong New Wave to the 70's and early 80's, and specifically referring to a group of foreign-educated filmmakers who came back to Hong Kong and created films that looked dramatically different from other mainstream films. For example, Shaw Brothers productions at the time wouldn't be considered part of the New Wave.I know the English wiki page follows Cheuk's assertion, but the Chinese wiki page is more accurate. The description of the Chinese version of Cheuk‘s book also dates it from 70s to early 80s.

Earl Jackson

At the risk of sounding weaselly, I would like to defer the question to Hong Kong cinema specialists since I am not one. However, what I can say is this: a movement and a genre are very different things. Any debate over the extent of Hong Kong New Wave is more instructive than, for example, what films can be included in film noir and when did film noir definitely end. Moreover, the debate of Hong Kong new wave has more at stake than Japanese New Wave, by virtue of the fact we're talking about Hong Kong. Hong Kong has been excluded from history in so many ways, such debates are always going to be conditioned by that exclusion. I find Victor Fan's suggestion that there are two new waves – an artistic and commercial – compelling. I would only add that the achievements of the “commercial” side ultimately make the division between commercial and art moot – something that postmodern studies also did. Along these lines -I urge people to read Fan's “What is Hong Kong Cinema” in his book Extraterritoriality – because every aspect of questions of definition, lineage and cultural “identity” are in play in these questions – What is Hong Kong Cinema? What is Cantonese Cinema? etc. My other recommendation is to remember that these questions and explorations are taken in good faith and even disagreements -strong ones – should reflect that awareness. We get a lot farther in conversations when we wrestle with the questions instead of the questioners.

Victor Fan

I think that the debate on when the Hong Kong New Wave began and when it ended (or, according to Cheuk Pak Tong, it is still going on) is a moot point, precisely because it depends largely on what we mean by the ‘New Wave'. In “Extraterritoriality”, I deliberately leave the definition open. This is because unless we have an agreement on what we mean by the New Wave, there is no way we can really define its starting or ending point. Moreover, if we regard history as a ‘process', rather than a series of phases, we cannot really say where it formally started and where it came to an end. From a purely industrial perspective, most filmmakers in Hong Kong would probably agree that the New Wave emerged on television in the mid-1970s. But then, we forget that the critical discourse that made the New Wave possible was already active in the Chinese Students Weekly in the 1960s. Meanwhile, in the 1980s, while some New Wave filmmakers turned to mainstream industrial feature filmmaking, others turned to video art.

Personally, I do side with some critics around the 1980s, that after the release of Long Arm to the Law, it was difficult to justify that a wave persisted in the mainstream film industry. This is not to say that other filmmakers who started their careers in the 1980s like Fruit Chan and Wong Kar Wai did not propel the industrial towards a new moment, but they had no actual connection with the Chinese Students Weekly Group and the Phoenix Film Club. They were also not part of the group of directors who flourished in television directing in the 1970s. They definitely represented a new generation of filmmakers already, even though they might have been inspired by the earlier generation. However, those filmmakers who became experimental filmmakers did go on with their experimentation in the 1990s. Many people may disagree with me, but interestingly, in experimental film and video making, there is indeed a strong lineage from the New Wave. After all, Ying E Chi is still one of the most important producers and distributors of experimental films and documentaries today.

Freddie Wong

Hong Kong New Wave Cinema started around 1979, with young directors like Ann Hui, Allen Fong, Tsui Hark, Yim Ho, Cheuk Pak-Tong, Lau Shing Hon, Dennis Yu, Peter Yung, Kirk Wong, Clifford Choi, Patrick Tam, Alex Cheung, Terry Tong,etc, all made their debut feature films circa 1979 – 1982. All of them, with few exceptions, studied filmmaking abroad ( especially in UK or USA ), returned to HK, gained experience in TV stations, making TV dramas, very often in 16mm film format.

I don't think there was a second HK new wave at that time. People like Stanley Kwan, Mabel Cheung, Alex Law, Wong Kar-wai, Mabel Cheung, Fruit Chan, were referred as Post-New Wave ( 後新浪潮)directors, but never “second new wave” directors, at least not in this part of the world.

It's interesting to note that the second HK new wave, which I called Fresh New Wave in my recent article, started about 5 years ago, with very young film directors, most of them studied filmmaking in local universities, and were able to make some decent debut films, telling genuinely Hong Kong stories. To quote a few : Ten Years, Weeds on Fire, Trivisa, Mad World, Still Human, My Prince Edward, Beyond the Dream, Time ( not yet released ) The Fresh New Wave of HK cinema is probably not as “high”and glamorous as the First New Wave, due to the unfavourable economic and political situations in Hong Kong in recent years, but it's going to be a long long battle for this youngest generation of Hong Kong filmmakers.

Bastian Meiresonne

The term “New Wave” originated from the French cinematographic movement “Nouvelle Vague”, which lasted mainly from 1958 to 1962, sometimes said up until late 1960s by some critics. Directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol or Jacques Rivette, born in late 1930s, wanted to go against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), explored new approaches to editing, visual style, and narrative, as well as engagement with the social and political upheavals of the era. It influenced generation of directors worldwide – even if critics and researchers would nuance its real impact and place it within a universal tendency of a young generation going against traditional forms in a fast-changing world, and some filmmakers adapting same techniques without having directly being influenced by the French New Wave. Ever since, any batch of new directors emerging in any country over the world are fast to be labeled “New Wave” – in some cases, it defines merely a handful of titles which come and go without any particular impact.

In the case of Hong Kong, would the term “New Wave” actually match France's original movement or is just another “label” put quickly on something going on? A much-discussed matter right from the start among industrial and institutional players, but also among some of the particular directors, who, back at that time, even rejected the label more or less. In short and in my very humble and personal perspective, it might apply to them: a batch of Hong Kong directors emerging at late 1970s / beginning of 1980s, rejecting Shaw Brothers' hugely implanted studio system, going against traditional filmmaking conventions and repeating formulas, and exploring new approaches to editing, visual style, and narrative in a bright diversity of genres such as fantasy, martial arts, crime and horror movie. They would take the cameras out on the street, some filming in almost documentary guerilla-style, not hesitating as to include some social and political upheavals of the era. Like their French colleagues, most of them were “intellectuals”, very well educated (sometimes in foreign countries) and having had the advantage to be well trained during their work in television (which, finally, was the real “New Wave” turf during Hong Kong's golden age of TV during the 1970s, where almost anything had been possible). And as diversified the genre movies and outcoming results, they all had in common the same bleak vision of (most of the time) contemporary Hong Kong.

However, opposite to their French colleagues, they didn't share a common ideology. They were no group, they were barely connected with each other, and they did not push all together into one and the same direction. No, they were newcomers with a huge appetite to change things, bring their ideas ahead – and eventually looking for some sort of success. And this means also a rather quick end to the so-called “New Wave” – or “First New Wave” as some critics and researches defined the first batch of directors. After some daring and sparkling beginnings, most of them turned to more commercial projects, sometimes even working with some big commercial studios, new or old, reigning over theaters, box-office and general audiences back at that time. Because real change does not occur overnight – especially in something as settled as big old pal “movie industry / business”. Just as a wave comes and fades away quite quickly in time (unless it is a “tsunami”), in my personal opinion HK (First) New Wave faded after only a few years, 1984 to give an exact date.

Some critics and researchers say the Wave lasted on with other directors entering Hong Kong's movie scene during 1980s, such as Stanley Kwan, Wong Kar-wai, Mabel Cheung or Alex Law. As much as I love their work and can say some of them had some impact on Hong Kong Cinema back in the 1980s, most are a few years younger (digging difference of life experience, history background and personal perspective), entered Hong Kong industry at a very different moment, at a time when their predecessors had already brought big changes, did not share the same vision of first batch and had really different approaches of the directors preceding them. And most didn't experienced HK TV's golden age the first batch lived through and mostly contributed to. This means by no way any devaluation of their work, just that I see them as “heirs” of the (first) New Wave, a “Second” Wave to say so…even if I think that term a less appropriate and almost more reducing word than to call them “heirs”.

Non-exhaustive list of personal most favorite so-called “New Wave” movies list

(Special mention to Patrick Lung Kong, whose STORY OF DISCHARGED PRISONER (1967), and even more his YESTERDAY, TODAY, TOMORROW (1970) and HIROSHIMA 28 (1974) was a “New Wave” all to himself in HK Cinema !!).

JUMPING ASH (Leong Poh-Chi, 1976)

THE EXTRAS (Yim Ho, 1978)

AFFAIRS (Stephen Chin, 1979)

THE SYSTEM (Peter Yung, 1979)

THE SECRET (Ann Hui, 1979)

THE HOUSE OF THE LUTE (Lau Shing-On, 1979)

COPS AND ROBBERS (Alex Cheung, 1979)

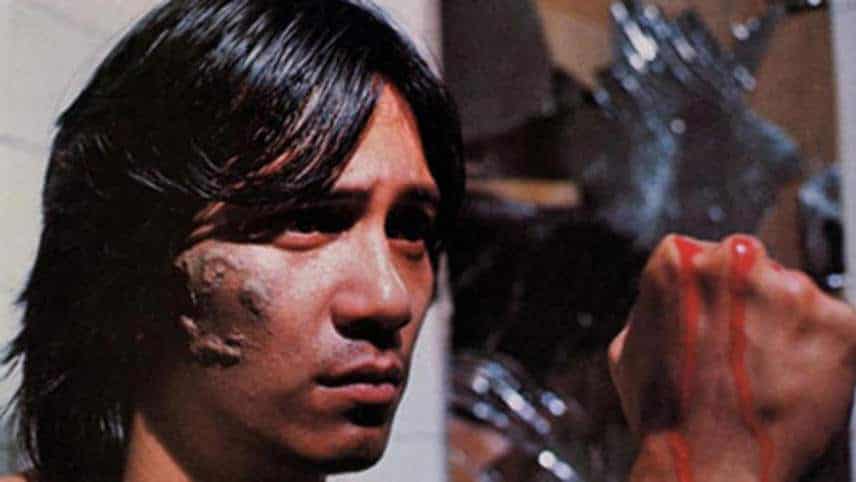

DANGEROUS ENCOUNTERS OF 1st KIND (Tsui Hark, 1980)

STRUGGLE TO SURVIVE (Hua Yi-hong, 1980)

THE HAPPENINGS (Yim Ho, 1980)

THE SAVIOURS (Rony Yu, 1980)

MAN ON THE BRINK (Alex Cheung, 1981)

FATHER AND SON (Allen Fong, 1981)

NOMAD (Patrick Tam, 1982)

LONELY FIFTEEN (David Lai, 1982)

AH YING (Allen Fong, 1982)