Jeff Kaufman and Marcia Ross's most recent documentary on Nasrin Sotoudeh is bittersweet. Sotoudeh, often dubbed the “Nelson Mandela of Iran,” has long become a household name for her human rights activism and hijabi rights in her home country. The fight for justice is fraught under an oppressive regime, however. In 2010, the government detained her for the first time in the infamous Evin Prison. After a brief period of respite between 2013 to 2018, she now sits in the even worse Gharchak Prison for a slew of unfair charges.

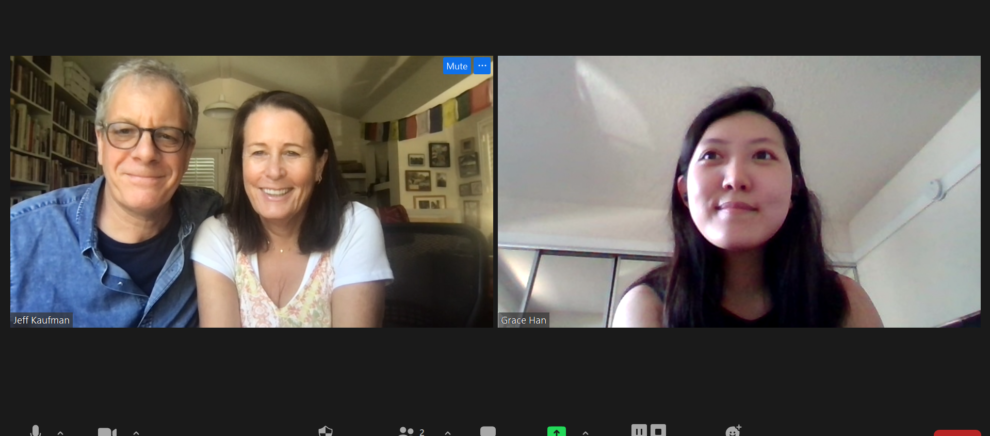

Perhaps this explains why “Nasrin” (2020) was entirely filmed in secret. From 2016 to 2020, Kaufman and Ross did not publicly mention the film at all: no announcements, no disclosed film crew, no prior press. On the occasion of the film's release on multiple OTT platforms this week, the documentary duo share with us some of the details kept under the wraps over the years. We dig deep into their creative process, their relationship with Sotoudeh and her husband Reza, and the film's ongoing awareness campaign.

This interview is redacted and edited for clarity.

What compelled you to make a film about Nasrin Sotoudeh?

Jeff Kaufman: I've done a number of films about human rights in Iran, [some of them] with Amnesty International. We filmed one called “Education Under Fire” (2011) about the persecution of the Baha'i faith in Iran and the development of an underground university system that allows Baha'is to go to college. Story after story, I was touched by the Muslim neighbors and friends who would put themselves at great risk to help Ba'hai friends and neighbors. It countered US stereotypes about Islam and Iran.

[In the process,] I was specifically moved by the example of Nasrin Sotoudeh, this great human rights lawyer who has fought for so many different groups: religious minorities, journalists, artists, opposition leaders. Marcia and I thought Nasrin just spoke to so many things globally and also to the US. When we started this film in 2016, Trump — who demonized a lot of the Middle East and Muslims — was just inaugurated in the White House. We thought that she could break a lot of stereotypes. She was the inspiration we badly needed.

I think your point about anti-Muslim sentiment in the US is cogent; the documentary could have easily walked into the trap of glorifying secular or Westernized approaches in Iran. How did you navigate this space?

Marcia Ross: For Nasrin, It's bigger than hijab or no hijab. It's about justice. There's this moment in the film when she takes this piece of cloth and says, “It's not enough for the government to say that tomorrow, we don't have to wear anymore. We want to have rights, our rights, to decide what we want to do.” It's not for the authority, the government, to be the masters of what we do or not do.

Jeff: It would be ironic to capture the American narrative of Iran and to put our own on it instead. Part of our process is to be respectful, to really channel the voices of the people we're dealing with. We've done films about Broadway, pioneers of the marriage equality movement, Haitian priests, jazz and Harlem in the 1930s – all of these are different stories – so we want to be as respectful as possible and channel that. We see in both countries too often building the barriers. A fundamental part of the Iranian regime is to disregard outside influence. We see that in our country as well.

I want to tease this point out a little more. How did your creative process play out? Did you already know what kind of story you would spin on Nasrin — an internationally renown figure — prior to filming?

Marcia: We couldn't go [to Iran], as it was too dangerous for us — as two Americans with a film crew. We never would have been able to follow [Nasrin] at all. We would have been arrested, we would have been stopped. So to have her be followed by people who really blended into everything – we were able to capture things that we wouldn't have been able to otherwise.

Jeff: We wanted to create a community portrait of Nasrin. We wanted her to be our conduit to a larger group of women who are doing this remarkable work in Iran and to this rich culture in Iran. She's always using her public position, even from her prison cell, to advocate for others.

Marcia: Nasrin was really clear. She didn't want the film to be just about her.

Jeff: It also helps that Nasrin is such an interesting woman as a person. She's determined and tough, but she's also hilarious. She has this great smile. Marcia and I did a film a couple years ago about the marriage equality movement in the United States (“The State of Marriage”, 2015) with Rep. John Lewis. He's one of those people where all those wonderful qualities you see in public, you see in-person too. He's warm and funny, just as he is in private and in public. It helps to have a central character with that kind of dynamic.

You both also mention secret filming and safety. How did that work?

Jeff: Everyone who was behind and in front of the camera had to sign a 2-page legal release that we translated into Farsi. [In retrospect,] we realized that this could have sent some of them to prison. Now, thank God no one has actually gone to prison, but the courage was so moving. We had to find people who we and she trusted, and shared those values with Nasrin.

Sometimes there would be one sequence where we'd log the shot, but we would only get one half at a time. Sometimes we'd see only the second half and the first half would come six months later. It was fascinating putting it all together.

Marcia: Moreover, we don't speak Farsi. Jeff did his usual routine — he logged every single shot — and then we sent the footage off to these two incredible translators. Then we revisited them, to see what everyone was actually saying. Jeff ended up with an 800-page tome of scenes and different themes in the film.

Jeff: 800 pages of notes and historical documents that eventually boiled down to a 65-75 page script.

Marcia: In the final stages [of post production], we also had our editor work closely with the Farsi translators to capture conversational context. It became really important for us to match the spirit and intention of what was being said. We worked with some really wonderful people.

Did Nasrin and Reza see the final cut?

Jeff: Reza saw the film. He was very moved. Nasrin couldn't see the film until she was on medical leave a few months ago. She caught COVID in prison and had a terrible heart condition. She was released for about 2 weeks to get some medical treatment. It was amazing. We hadn't seen her in 2 and a half years — she had been in one of the worst prisons in the world — yet she was so funny, and so charming, and was very complimentary about it.

Did her second imprisonment catch you all off-guard at all? Did you have back-up plans for your production?

Marcia: It was very upsetting. [For a press release,] Jeff and I both had to answer a prompt about our most potent memory of the film. We answered separately, but got the same answer: one day, we were Facetiming on Whatsapp with Reza and her. They were in a park in Tehran. We were in New York at the time.

Jeff: It was an hour-long conversation and the sun was going down. They were walking toward the trees.

Marcia: Two days later, we got an email saying that she's arrested. It was devastating. The worry about her safety and well-being had been with us since that moment on.

I've come to believe that she, on some level, knew that she would be [caught again.] She could have left Iran after the last time, but she chose not to. She loves the country, the people, and wants to make change from the inside. She used the film as an opportunity to say to the world what she wanted to say, in case she was silenced. Everyone knows now what she thinks. The film exists.

I was also really moved by the last phone conversation that she has with her family while she's in Evin Prison.

Jeff: You can just imagine what a privilege it is to be allowed to enter someone's life like that. Right now, she's been transferred to the even worse Gharchak Prison. She's in a cell that's 13 feet by 10 feet wide with almost a dozen other prisoners. There's no ventilation or windows; low ceilings; a constant stench of sewage; the food is poisonous; the water is salty. We're highly motivated to bring the attention of the world to her case.

Marcia: Whenever you speak to her, the first thing she does is that she talks about others. I think that conversation is so remarkable because of the way she's able to balance a horrible situation and still be a mom.

Jeff: That's why people call her the “Nelson Mandela of Iran.” I've never heard her express anger or vengeance. She's still pursuing a sense of unity.

Your film is premiering on Hulu this week. What do you hope “Nasrin” will accomplish?

Jeff: The film is not just available on Hulu – it's available internationally on www.nasrin.com. We're launching a new international campaign on the behalf of Nasrin and all of the remarkable people. It's an ongoing connection of seeing the film and getting her and the others out. It's not just about [Nasrin], but about bringing attention to other political prisoners too.

Nasrin was really inspired in her work by Nelson Mandela, Gandhi – they gave her a spark that has changed many lives. We think Nasrin can do the same for others. Pass on that spark of responsibility, of mutual respect, of fighting for human rights. Nothing would be more gratifying than to think that a generation of young human rights activists are inspired by Nasrin by seeing this film.

Marcia: We always thought we'd have an impact campaign because of who she is and the work she does. [Following her arrest,] it just became imperative to tighten it all. These have been very important for her protection. Governments like Iran's respond to a certain amount of shaming; it's hard to [take torture and imprisonment further] when so much international attention is focused on a certain individual. Her global recognition and the film have provided a safety blanket from the worst of the worst.

On a more personal level, Reza follows everything that we're doing. He speaks to her regularly, tries to see her once a week. He has told us when she goes to sleep and closes her eyes, she pictures everything we've done. It gives her hope. That just means so much to us.

Finally: Do you have any other future projects? Will you return to Nasrin, to Iran?

Jeff: We're working on some other things right now. We're still in the percolating process.

Marica: Until she's home and she's free, this will always be something we'll be working on in some way or another.

“Nasrin” (2020) is now available to view on Hulu, Amazon Prime, Apple TV, and Youtube.