Translated by Lukasz Mankowski:

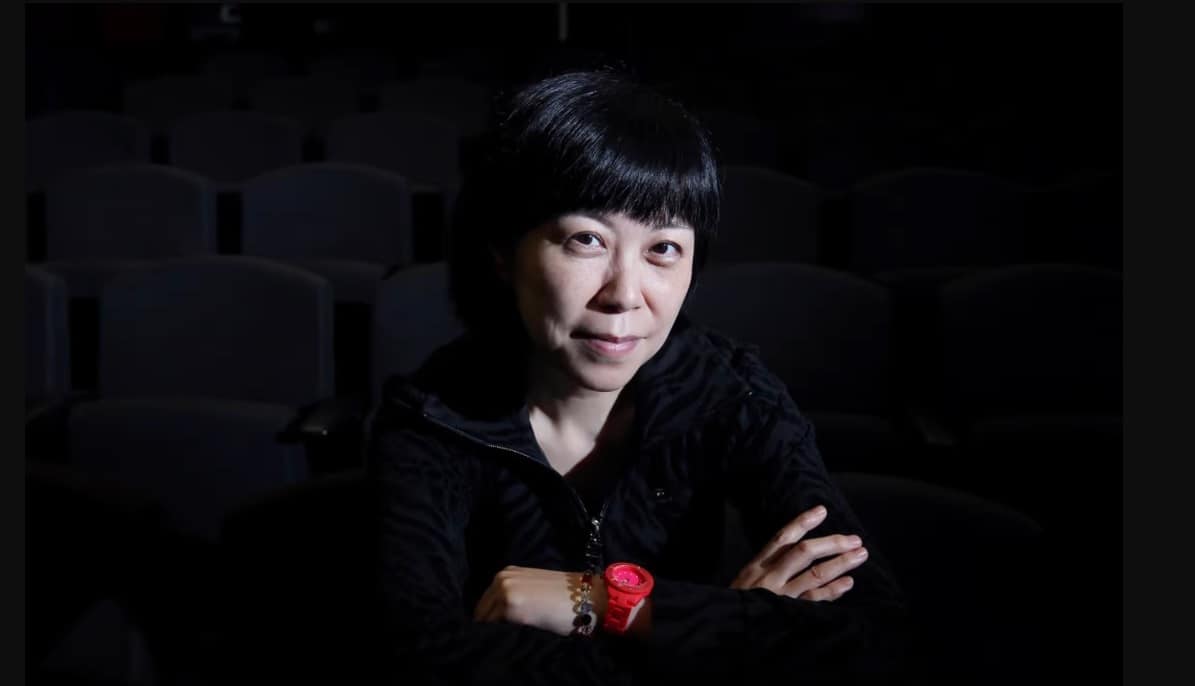

Born in 1977, Miwa Nishikawa is a director, screenwriter, producer. Studied literature at the Waseda University, started her film career as the assistant of Hirokazu Koreeda, who produced her debut, “Wild Berries.” The film received awards at the Yokohama Festival, Mainichi Film Concours and the Japanese Professional Movie Award. Her following, award-winning productions were also well-received. “Sway” (2006) was presented in the Cannes Directors' Fortnight section, its script received the literary Yomiuri award and soon came out as a novel. Nishikawa also published a set of short stories “Kino no kamisama” and a novel “Nagai iwake.”

On the occasion of “Under the Open Sky screening at Toronto Japanese Film Festival, we speak with her about shooting her first novel adaptation, the world of Yakuza in the past and now, Koji Yakusho and Meiko Kaji, music and humour in the film, and other topics

All your previous movies were from your own original scripts, but «Under the Open Sky» is the first time you adapt a novel. Was it a difficult decision and what where the most significant differences with your previous films?

The author of the novel the film was based on, “Mibuncho, is Ryuzo Saki. He was known for his unique style of conducting very intimate interviews with real criminals. That's how he collected material for his novels. When he passed away in 2015, this was the moment I found out about“Mibuncho”. I instantly picked it up and I was immediately impressed by the story. Unfortunately, at that time, it was out of print so it seemed that the book was completely forgotten by the rest of the world.

I actually admired Saki since I was a young novelist myself, so when I discovered this story, I had a feeling that I truly discovered something one of a kind, a raw gem whose existence is known by no one but me. I thought that I need to use this opportunity to fascinate other people with the charm of the story. I decided to reissue “Mibuncho” with the publisher. There was no slightest hesitation from my side.

The biggest difference from the previous films that I directed is that the protagonist of this story is not someone with whom I'm familiar. Since the narrative revolves around one's reality after a long penal servitude, I needed to be just like Saki. I had to make research on my own and be able to write the dialogues even with my eyes shut. What was also important, is that the novel was released in 1990, so I had to adjust the story to contemporary times. Most of the alterations were done regarding how the system works now. I needed to make research about that, too, with plenty of materials, interviews and reading done in the pre-production.

What is the situation with the yakuza nowadays? Are they essentially victimized for their past ways? The laws about them seem like a sort of punishment. What is your opinion on this aspect?

Even though some of them have already left their organizations, the police and the law maintains that the yakuza still can't rent a house, open a bank account, or even set up a mobile phone account under their official name until more than five years have passed. They face a peculiar dilemma – they're not in the organization anymore, but neither in the society. Also, just like in the story of the film, one shall not receive welfare protection, even if they don't have a steady income. In other words, it works like this: “Stop Yakuza. But, don't let them live their lives”.

They are excluded by society, their organizations have no regulations nor control over them anymore, and yet, they still hear from the society about how much they are involved in a dark world of serious crimes, which revolve around regular citizens and get worse and worse. I think that the type of stoic yakuza films – which were based on heroism, and which were truly endorsed by the fans – this era is over.

I think this is a result connected with a heartless and shallow way of thinking that Japanese society abounds in, this is to say, a belief that everything that is inconvenient and one does not want to see around them will naturally disappear and rot away if you take that thing out of sight. People in general are creatures that desire to punish others. I think this is misleading optimism. Once one is punished, then they rehabilitate, and, eventually, it is not necessarily the case that it will bring an improvement for society.

The film could easily become a melodrama, but you avoided this approach, mostly by inducing humor into the narrative. Can you tell us a bit more about this approach. How important is humour for you, both in movies and in real life?

Since my film concerns social and serious issues, I believe it's important to plan it in a way the audience will have the desire to watch it till the end. I wanted to emphasize the protagonist's extreme personality and depict his eccentricity and many failures he experiences in a rather warm and humorous way. For that reason, the audience, slowly and gradually, starts to sympathize and relate with the character. We think of lending him a hand, helping him a bit, being there for him. This “lightness” is something that I wanted to lean on as much as possible.

Humour is the most difficult to express in the film. I'm still learning about the complexity of it. I'm wondering if the ability to make people laugh while telling about something important is the most important of all the abilities, both in life and in films? Frankly speaking, I think so.

Particularly the two scenes involving mail ports in apartment doors are hilarious. Can you give us some more details about them?

The scene with Mikami's apartment's door overlaps with the viewpoint of the two-man crew from the TV. They peek at Mikami's privacy, so the audience also inherits this point of view, starting to perceiving him as a “dangerous man”, just as the visitors in the zoo observing an animal in one's cage. The thing is, Mikami in the cage is not an obedient creature that will just wait and stare back; he's a sensitive one, very well aware of what's going on around him. He might react to those peeking at him from the outside. Biting back is an option. Doors in the Japanese old apartments had a hole for newspapers, so in a way, this is a reflection on the dynamics of direct peeking from the outside to inside. That's why I used this scene.

Regarding the scene in the apartment complex, Mikami used to be a person who had committed many minor crimes with almost no remorse. He would cross the line among society quite easily. That kind of person he was. When he's out of prison, he can be suspected by others, so he doesn't want to do things that police might simply arrest him for, but he remains quite stubborn. I guess Koji Yakusho's nuanced performance is also the reason that the scene that might appear as a frightening one even for the little kids, here receives a rather comical appreciation.

The role of the TV producer is rather despicable. Is that how TV people work essentially?

Of course, this does not apply to everyone, but the competition of audience rating is a real struggle among the commercial television stations, so the numbers have to be right. Rather than asking themselves a question “what do we want to convey in our programs?”, people in the TV industry are stuck in a peculiar sense of values: “let's make such a program that more and more people won't change the channel”, just for the sake of doing it. The audience is already aware of the dishonesty of that logic, and the young generation is gradually drifting away from the TV medium. That's why I think the folks in the industry are at a crossroads. With that being said, since I'm also often in a position where I interview people, I can in a way sympathize with them, with the self-abhorrence they struggle with, and the departure from what lies within the reason – that is an approach they seem to keep plunging deeper and deeper in.

Can you tell us a bit about the casting? How was your cooperation with Koji Yakusho and Meiko Kaji. Particularly the latter had not acted in a movie for quite some time. Was it difficult for her playing?

Meiko Kaji has been an actress since the time Japanese major studios mass-produced program pictures, but I believe this role wasn't particularly a detour from her usual oeuvre, which is a bright and broad-minded role. She has had a lot of experience working on series recently, so it seems she was very ambitious about playing a role that hasn't been in her scope for quite some time. Kaji-san is very friendly and gentle, incredibly nice to the staff, and appeared to be a great senpai to all of us.

As someone who survived the very harsh environment of film sets from the past, during the shooting, she showed nothing but great manners, astonishing patience, and has not uttered a single complaint. Yakusho-san, who has also experienced a lot of struggle during his early days, once said: “The sets back in the day were tough. This wasn't the atmosphere where one could speak his mind to a film director”. And in a sense, the style of working of these two is quite similar.

When we were shooting the scene when they both appear, that is, when Mikami's vintage sewing machine suddenly breaks down, we had to spend some time to capture that scene due to the necessary repairing. We would stop recording for long intervals but they would remain in their poses, just like bronze statues, not even twitching. They just kept silent and simply waited for a retake. That tells you something about veterans… I imagine that's perhaps because they managed to endure the strictness of the old times of the film industry.

Music plays an important part in the film. Can you give us some details about the tracks and your goal in that aspect?

Music in film is an extremely important factor thanks to which one can emphasize joy and beauty or strengthen the appearance of a world. I've already said that about humour, but since the theme of the film is quite serious, I guess music saved me to make it a bit lighter on multiple occasions.

With that being said, since the influence of music is vast and strong, it can change the interpretation of the image in a moment and change what it originally meant to convey. That's the magic of it. When the score is changed just by one note, the audience's perception can also be guided in a different direction. That's why the composers often tell their instructions to the actors and others in a very in-detailed way. However, just because one piece is good, it doesn't mean it works well for the image. When the score says too much, it diminishes the visuals or performance of actors, erasing the invaluable rawness of these two elements.

Therefore, as one of my principles, I try to shoot good material, edit it the best way I can, and then try to make it work without music. Otherwise, even with having a piece of great music, it will turn out as an over-cooked and over-wrapped cookie. This time I worked with Masaki Hayashi. Even though he composed beautiful pieces for the film, I had to reject some of them on multiple occasions. And this was music he composed with all his heart. That was a very exhausting moment for us.

When I think about it, there is a moment in the film when Mikami and the boy play football and at some point, we decided to make a rough recording in the studio to match the image with some music. It turned out perfectly. The tune wonderfully matched the scene, giving this very moment a miraculous vibe. Making music abounds in these little wonders and tensions.

To be fair, if one can have slightly bigger budget on the score, it is possible to weave together musical masterpieces with outstanding performances. But, with how things are in Japanese film industry these days, with the way how financial situation here looks like – it's quite difficult to achieve it.

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

I still haven't decided about the specifics of the project, but I'm currently in the process of delving into research. I'd like to go back in time a bit, to work on something relating to the old days, that's why I have been reading and collecting data a lot these days. I read everything I can lay my hands on and it's piling up. I hope to do my best with this film and show something entirely new and fresh, so please bear with me. All I ask is a bit of patience.