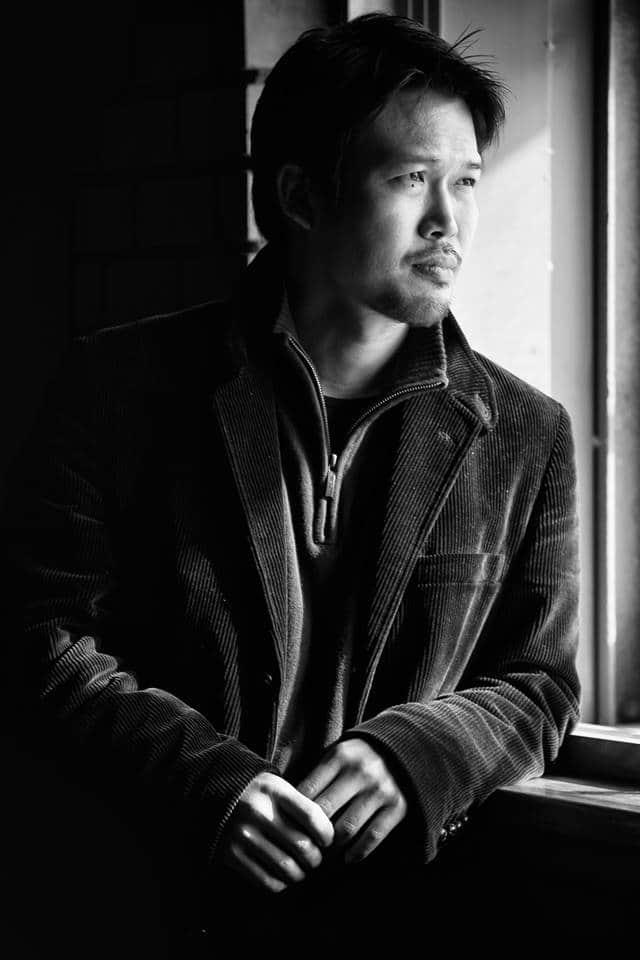

Yoshihiko Ueda is a director, photographer, and Professor of Department of Graphic Design at Tama Art University.

He was born in 1957 in Hyogo Prefecture. Among his many awards are the Photographic Society of Japan Lifetime Achievement Award, the Tokyo Art Directors Club Grand Prize, and the New York Art Directors Club Photography Award. In 2011 he launched Gallery 916. His most noted series/monographs include Quinault, a meditation on the eponymous sacred Native American rainforest; Amagatsu, a backstage study of Sankai Juku dancer-choreographer Ushio Amagatsu; at Home, intimate snapshots of the artist's family; Materia, capturing primeval sources of life; and A Life with Camera, a collection of works from his massive oeuvre spanning over 30 years. Recently published are FOREST: Impressions and Memories 1989-2017, capturing the three primeval forests of Quinault, Yakushima, and Nara Kasuga Taisha shrine, and 68TH STREET, a memory of light and shadow falling on a single sheet of white paper.

In 2019, he wrote, directed, and filmed the movie “Garden of Camellias”, the story of a woman who loses her husband and is confronted with the inheritance tax on her home, depicted through the changes of the seasons of a traditional Japanese house and its garden.

On the occasion of “A Garden of the Camelias” screening at Toronto Japanese Film Festival,we speak with him about transitioning from photography to film, the house that appears in the film and the way these kind of building are becoming extinct, having a multinational cast, and nay other topics.

translated by Lukasz Mankowski

How did you find the transition from photographer to film director for your debut?

I feel that this change was a natural progression of my pursuit of possibilities in the visual area. What film and photography has in common, but also what exists as a big gap between these two, is that for the past 40 years, I've been capturing the vividness of times by using such magical tools as my camera and film. At some point, I realized there's also a cinematic expression that stands in front of me. As a result, I really started to savor every blissful moment of the creation process that I got an opportunity to delve into. I was simply charmed by the beauty of cinema.

What was the initial inspiration for the story of “A Garden of Camellias”?

About 15 years ago or so, I used to walk a lot nearby the place I lived in and there was an old house with a huge garden, which I used to like very much. I would always peek at it every time I took a walk. But suddenly, the house was gone, so were the trees in the garden. It was demolished. For some reason, I felt a strong, overwhelming sense of loss. The scenery that I remembered that well, was gone. That feeling was the reason for my desire to make the film.

The particular house in the film plays a very important role for the narrative. Can you tell us a bit about how you found and why you chose it?

This is an old house and it is set on the high ground from which one can see the sea. It's actually a very important place for me. That's why I had it in mind from the start. When I wrote the script for the film, I knew I want to set the story there. I wrote it thinking about this particular house.

What are your hopes and fears for the future of houses and gardens such as the one featured?

Currently in Japan, it's very difficult to preserve such old houses and gardens like the ones in the film.

For instance, there is less and less people who deal with the craft, carpenters or artisans, so there are no people who would build such a traditional house. Also, because of the peculiarity of Japanese inheritance tax law, it's extremely difficult to pass the old houses to the next generations. Many people have no choice, but to part with their beloved homes.

The other thing is the lifestyle change. An increasing number of generations do not particularly find the traditional way of living appealing, this is to say, one in which one's house would include Japanese unique design, with having tatami, shoji sliding doors or fusuma panels. As a result, this is actually the majority of society that regards these elements of interior design entirely as the representation of oldness.

That's why, by connecting the beauty of the Japanese form of traditional houses with as many people from the younger generation, I hope I can still make the legacy of Japanese unique scenery last longer.

Initially the film feels like something of a nature documentary, with close-up shots of nature and the humans fitting within this setting. Was that intentional? In general, what was your purpose in the visual aspect of the movie?

I wanted to express the Japanese concept of mujo, the impermanence that might be found in everyday life, the ordinariness we face every day in front of our eyes, which we call the time. Within that, there is the same usual scenery you always watch and think about, one that you are so familiar with; or the trivial things, there's so many of them; or seeing your family.

However, I think that truth and existence are proven to be there, because of the time that flows when absolutely nothing happens. In one moment, when you can't see the same thing two times, this is when you experience the scene of impermanence. Don't move and watch the leaves swaying away from the trees delicately. Or the rain, that soaks the parched roof tile with the dripping water. Or the flower that blooms and falls to the earth, dissolving its colours as it melts into the soil. The life and death of a tiny insect; the sky, the cloud, the living and dying of all the entities.

This performance of the mundane is equal to the one of ours, human beings. In my film, I wanted to depict everything equally, whether that is human or a flower, a bug or a tree. I treated everything the same. Human beings also melt together with the world. I made my film with a belief that the whole picture can naturally appear as one, when I will collect the tiny details and fragments depicting elements I've just mentioned.

Nagisa has been away from Japan and is having to re-learn Japanese language and culture. What was the thought-process behind her having her foreign background?

Nagisa was originally appearing in the script as a 12-13 years old girl. A girl who's very complicated and who's not an adult quite yet. During the casting for the role, I was introduced to a young actress from South Korea, who has just arrived to Japan at that time, Shim Eun-kyung. At that time, she was still barely speaking any Japanese, but despite this I was extremely impressed by her ability to express her character and her feelings with just a little amount of words and body language. In that moment, I realized what I was looking for the character of Nagisa and I immediately decided that Nagisa will be that kind of a person.

I decided to rewrite the parts of Nagisa with Shim havingher in mind as the heroine of my story. Firstly, the change was that Nagisa was born in Seattle. This is because I used to visit Washington state to take the photos of the Quinault Forest, and I went there repeatedly, so the picture of Seattle stayed in my mind.

The character of the oldest daughter, Yoko, whose marriage is opposed by her father, leaves Seattle with her husband and during the trip, it's Nagisa who is born on the ferry. The three of them lived happily since then. That was the setting.

In the last scene, Nagisa is reading the list from Seattle, but I think that Shim wasn't really able to read that. (laughs)

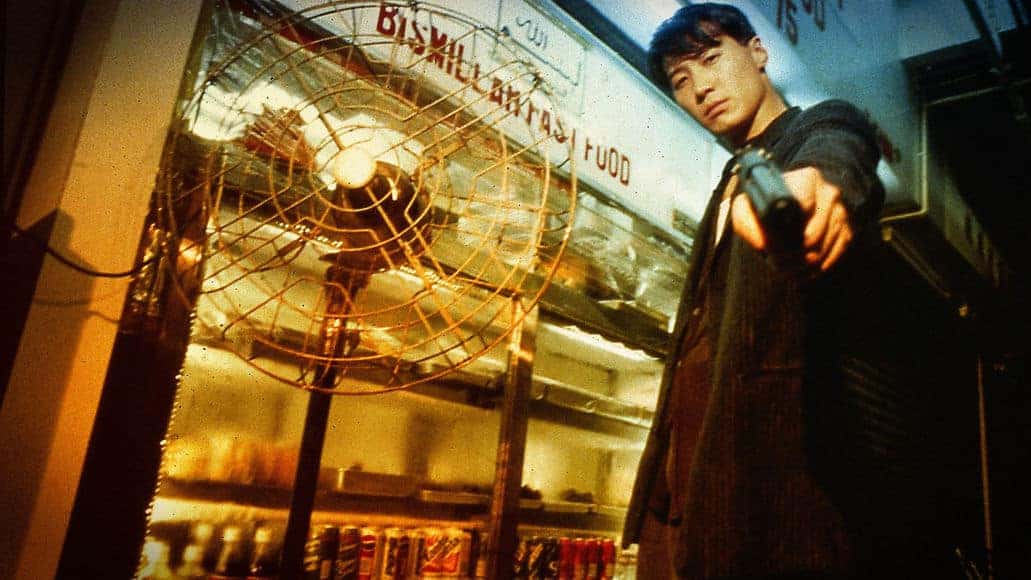

Can you give us some details about the casting, particularly about Korean Shim Eun-kyung and Taiwanese Chang Chen? How was your cooperation with them during the movie?

Initially, I wanted to make a film that would include the uniqueness of East Asia. In Canada or the United States, one is surrounded by people coming from different cultures and countries. It's the same in Tokyo. I wanted my actors, Shim Eun-kyung who's Korean, or Chang Chen, who's Taiwanese, and Sumiko Fuki with Kyoka Suzuki (who are Japanese), to act as a family, to naturally become close to each other. I wanted to shoot them in a scenery of mutual relationships.

I've just talked about Shim Eun-kyung, but with Chang Chen, we've been friends for 20 years already. But, for some reason, he didn't want to appear in my film, so frankly speaking, I simply wanted to have him for personal reasons. I don't know of any other actor from Asia who brings this unique atmosphere to the film with his personality. I wanted to use his presence to establish the particular scent of the film. And honestly, that's why I let him be himself. As for the others, I knew from the moment I started writing the script, that these characters played by Fumiko Fuji and Kyoka Suzuki, they have to be played by them and no one other.

Do you plan to continue filmmaking? If positive, are you working on anything new?

Of course, I'd love to keep on making films. When I finished “The Garden of the Camellias”, I realized that was one of the most joyful experiences I've ever had. The experience I have, with all my photos or music that I made so far has been great, but, to exaggerate it a bit, I felt that I was made just for films when I accomplished this one. I felt great joy.

Right now, I'm in the middle of preparation for another project. I can't give you any details as of yet, but the plan was to shoot this year. However, due to the Corona crisis we were forced to postpone it for the next year's spring, so we're aiming for that time. This film will also reflect on the topography of Asia, with the focus on the ordinariness of everyday life and people drifting through the beauty of the impermanence. I really hope to make it a beautiful one.