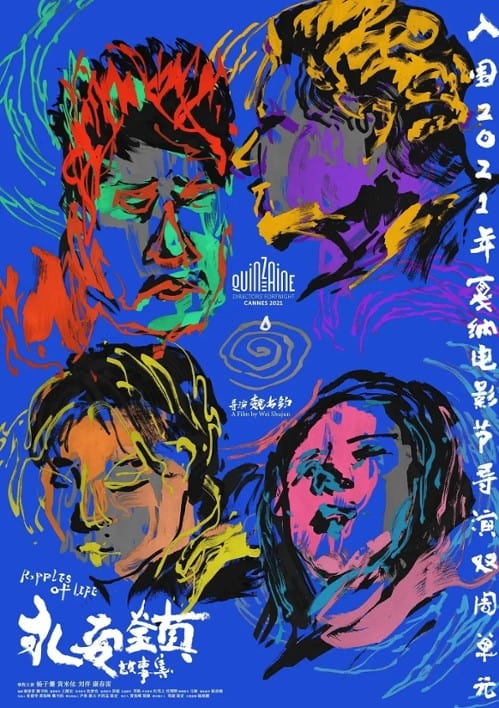

Films about filmmaking still receive a decent spotlight at the festival circuit. No better place than there, as they keep on scratching the delicate hearts of cinephiles across the world. The reflection of the auteur kneeling down to the misfortune of a creative slump; a possibility to coexist with the dramedy of the world behind the curtain, even if for a brief moment; the jokes and the laughter that come after guessing the right trope, the right title – we know it all. To fit that image and confront the audiences, comes Wei Shujun with his sophomore feature, “Ripples of Life” (premiered at the Directors' Fortnight Cannes sidebar), a three-tale story about the endeavours of the independent film production on a foray into Chinese small town.

Unfolding his narrative into three novels, Wei encapsulates different nuances of the indie industry. The film crew starts the pre-work at the small-town, where the ‘nothing-ever-happens' defines the mundane. The romanticized boredom that supposes to be a perfect match for the narrative needs. With the appearance of the film on the horizon, the citizens are sparkled – there's some hope for a change. Among them, Xiaogu, a heroine of the first tale, whose days are filled with bartending and caring for her family, a child and her husband. Since the star for the production seems to be hesitating about accepting the role, that ignites her desire to fill the shoes. Apparently, she has that something – she looks just like Kim Min-hee when she smokes.

However, once the stardom issue receives a slow treatment, Xiaogu is immediately forgotten. Chen Chen, a star born and raised in the very city, finally accepts the role and staves off all the doubts. This is the second story, in which the performance of insularity confronts the high hopes of both, the film crew and the city authorities, as everybody seems to drain the vitality of poor Chen Chen. The city has changed and so did the landscape of its citizens' needs.

The last segment is set on the verge of a constant argument – between the director and his screenwriter. They hit a slump of their own, and their hoped-to-be-a-hit “Ripple of Life” (singular) struggles to hop on a right track. They discuss their philosophy of cinema back and forth, delivering some genuine lines regarding the film industry and its dynamics. What is cinema, what is auteur, what is the audience – these are the questions that never get the right answers. The profoundness and wisdom of those who seek them, is always a treat to watch, as the meta-level discussion derives from the experience of the filmmakers. The title says it all. It's the mood for a film.

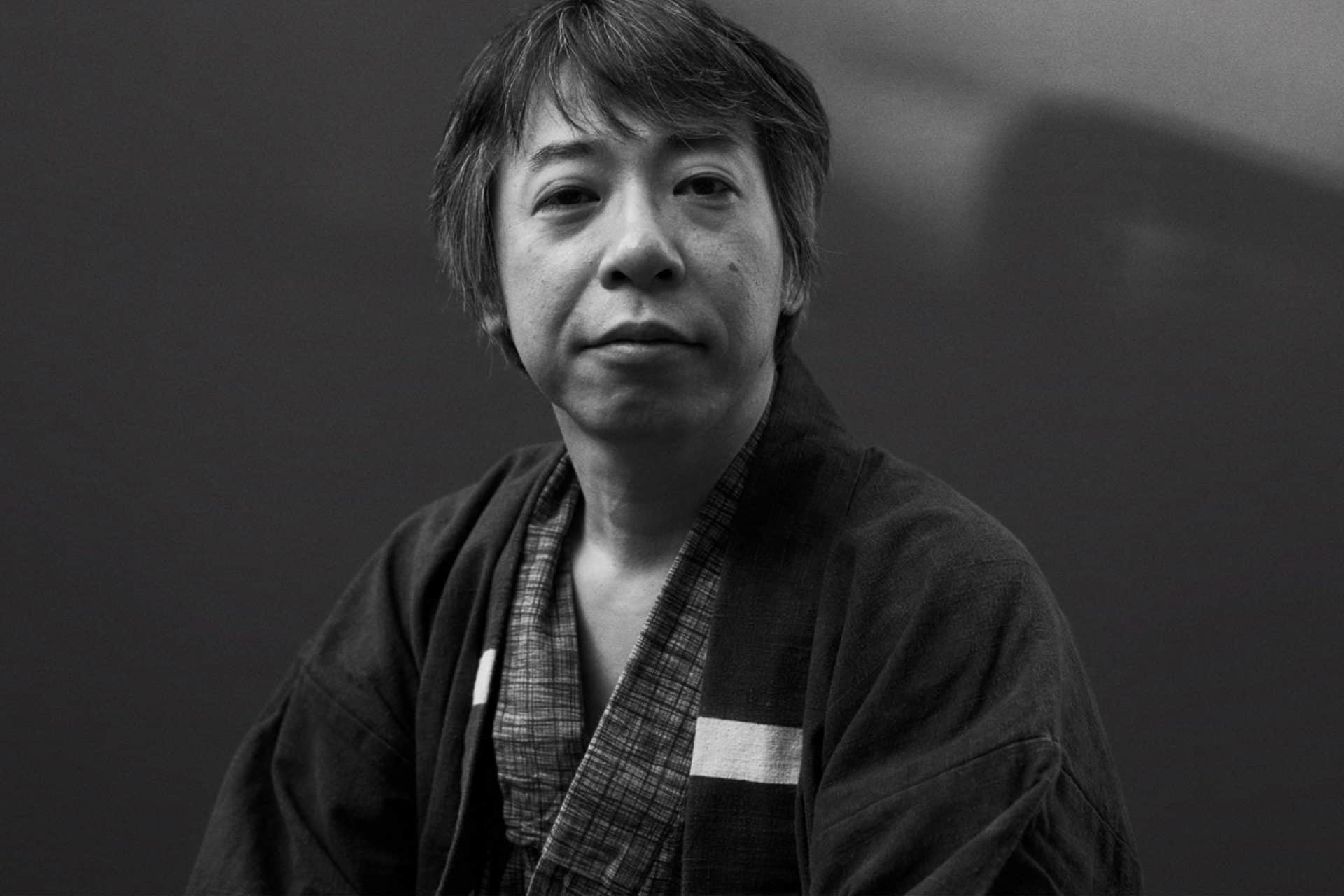

Due to the outgoing difficulties with travelling, we managed to meet on ZOOM during Festival de Cannes, one day after the first public screening. Wei Shujun seemed very enthusiastic about his film having an actual premiere (his first film “Striding Into the Wind” couldn't have its proper premiere last year, although it was accepted to Cannes), which he showed in our dialogue about “Ripples of Life”. While having a few cigarettes, he was eager to talk about the background of the story, the dynamics of the set, making films about filmmaking, and hidden meanings or details, including the influence of Maradona's death on the film's outcome.

“Ripples of Life” screened at Cannes Film Festival

First of all, how are you feeling?

I feel wonderful. Yesterday was the official first screening in Cannes, so I was quite nervous, but since we received a lot of positive feedback from the audience, I feel at ease now. When it comes to my films, the most important thing for me is my audience. I really care about each individual's feelings about my work, so I was really looking forward to the premiere at the festival.

Since “Ripples of Life” depicts the reality on the film set, I was wondering what did the atmosphere at your set look like?

That's a long story. To start with, I need to give you some details about the background of the film. After 17 days of pre-production of the initial project, I lost all the passion and enthusiasm for the first script. It was supposed to be a four-story film. The reason for the change was that the more I wanted the story to become a successful one, the harder it became for me and my writer. The more we tried, the worse it got. We started to hit the wall, so we felt we needed a change. We decided to rebuild the story. The crucial thing was that we wanted the audience to believe in the story. So we kept on discussing the script back and forth. We were really immersed in the dialogue, how it was supposed to look. If I don't believe the story, then the audience won't do it either; if it doesn't satisfy me, then it won't satisfy other people. That's the beginning. We started rewriting the narrative and a new story emerged within the span of 10 days, but the whole process was built on the mutual respect between me and the screenwriter [Kang Chunlei, who plays the character of the writer in the actual film].

The second important aspect is the dialogue with my producer. When we were in the process of rewriting the story, the whole crew was already on location, starting to work on the first script. And since we rewrote the story, we had to restart the whole plan and let the producer know. The biggest limitation back then was time, so we had to prepare a lot of things very quickly. That was the moment when I received a lot of support from my producer [Huang Xufeng, who also plays the character of the producer in the film], who kept on encouraging us and pointed all of us in the right direction. Thanks to that, we all stayed on right track till the end of the shooting.

Your previous film that was selected for the Cannes programme last year, “Striding into the Wind”, also explores the area of film. What is so tempting for you in delving into the theme of film-in-a-film?

This genre is generally quite typical if you look at the film through its history. A lot of famous directors, such as Hong Sang-soo or Woody Allen, also tried to make films about films. For me, the idea of making such a film comes from the idea of understanding the process of filmmaking itself and this process is also very important for me. It's also easy for me to approach film this way, through the process of its creation. The first two parts of the “Ripples of Life” basically explain how a film is being made. The first novel reveals the progress of preparations and gives an insight into the pre-production phase; whilst the second one poignantly conveys how real people perceive the film.

Speaking of real people – in “Ripples of Life”, the character of the screenwriter is played by the actual screenwriter (Kang Chunlei) and the producer by the actual producer (Huang Xufeng). Why have you decided to fit the roles with the actual filmmakers?

Each role has a different background. I'll start with the character of the writer played by Kang Chunlei. When we did the table reading of the script, I tried to fit into the role of the director and Kang read the parts of the screenwriter. We both wrote the script, so we both understood the characters very well. For both of us, there was a lot of emotional investment into these roles. We could also convey their mood very well. Since Kang understood the character's motivation, his acting was very natural. He almost didn't look at the script; he would just play along. It was very natural and he fit the role perfectly, so the decision to cast Kang Chunlei as the writer in the film came naturally.

As for the producer, I initially asked another director, Diao Yinan [the director of “Black Coal, Thin Ice” and “The Wild Goose Lake”] to play the part of the producer in the film, but he refused. It was actually the real producer of “Ripples of Life”, Huang Xufeng, who asked Diao Yinan in the first place. But then, Diao Yinan suggested Huang to play the producer himself. And indeed, again, it was more natural as Huang understood the process. Then I thought that it makes sense, because Huang knew the background of the film and all the details behind the changes we needed to include. This is how the writer played the writer and the producer played the producer.

But you didn't play the part of the director, even though you have a background in acting. I know that it was related to the lack of contrast between you and Kang, so the decision was conscious from the start. Since you started your career as an actor, I was wondering how the transition from acting to filmmaking made an impact on your approach as a director?

I considered myself for the role of the director, indeed, but comparing to Liu Yang, who I did cast as the director, I thought that I don't look young and sophisticated enough. And I wanted that contrast between the director and the screenwriter in the way they look and act. With me as the director, it wouldn't match the film. I did, though, play a police officer in my debut feature. Coming to your question – since I do have a background in acting, I do realize how exactly the actors think when they perform in front of the camera. The knowledge of emotional participation the actors have is crucial for my work.

You mentioned Woody Allen or Hong Sang-soo and their approach towards making films about films. Their films derive from their perspective, but also include a lot of fiction. How did the process of finding the balance between the subjective and objective vision look for you?

That's the second time I'm actually asked this question. For me, there is no such thing as keeping the balance, simply because subjectivity and objectivity always happen at the same time. Hou Hsiao-hsien once said: ‘There is always something that happens after people's reaction and that something happens under the influence of people's way of thinking.' That's all about details and subtle stuff. Drama happens everywhere, no matter if it's inside or outside. One just needs to pay more attention to notice where that real drama happens; pay attention to little things, the inner side of the drama. Then, dig into it and find out what's the main core of it.

Speaking of the drama and the details – you included the song from Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical, “Evita”, sung by Madonna, “Don't Cry For Me Argentina”. The adaptation of the musical (finally directed by Alan Parker) was a production hell. It took a lot of time to finish, with several directors shifts, and the crew barely made it to the end. The screenwriter of your film wears an Argentinian football t-shirt, there is mention of Maradonna's death. What is the story of these tiny details?

There are two reasons. The first one comes from outside of the script. We made this bold decision to destroy the initial script and rebuilt it into a new one, right? The crew wasn't happy about it. Not at all. They went really mad. At the same time, it was November back then. Maradona has just died. That news stroke me and Kang Chunlei (the screenwriter). We were all shocked. But, at the same time, we felt inspired. We felt we had to include it in our story.

The second thing is related to the flow of the script. The director and his screenwriter in the film, they cannot get along with their dialogue about the direction of the story. They always argue, right? Maradona's death gives them an idea – no matter what type of argument they have, no matter how serious it is, what they do need is a way back to life. Death is something that they think about all the time, but outside of the conflict; from the shocking news they can finally create something.

The news gives the idea on a meta-level. It starts from real life, but it influences the narrative in the script. After Maradona's death, I thought that we can make the character of the screenwriter more related to real-life thanks to him wearing a football t-shirt. As for the song, “Don't Cry For Me Argentina”, it works as a check for the dramedy for us; it's like a bird's eye view to look at who lives on Earth, onto the tragic life that happens out there. You hear the sad voice and you feel that the expiration date for one's life, that it's out there, very near – it's an encapsulation of our experiences.

The dialogues between the director and screenwriter in the third part are very dense. They argue back and forth and the influence of real-life gives an additional context. Since the arguments they have seem so genuine, I was wondering how did your relationship with Kang Chunlei look like during preparing the script and on the set?

Both of the characters, the director and the screenwriter, come from the mix of me and Kang Chunlei. In both of them, we have a glimpse of me, Wei Shujun, and my screenwriter, Kang Chunlei. Just because Kang Chunlei plays the writer of the same name, it doesn't mean he's exactly just that person. The dialogue is perhaps half inherited from our real conversations, but the rest comes from the drama that we experience on a daily basis, during our professional work.

The last mastershot of the film, when everybody's coming to the final group photo, it reminded me of Hou Hsiao-hsien's, who you've mentioned before, and his film…

Indeed! “A City of Sadness”.

That's correct! I was curious, what was the story behind the scene? It comes with a powerful song, we've just talked about, and everything connects with this one last still in a city, where nothing ever happens.

The original plan was that all the crew would stand there already waiting for the photo to come. Once I got on the set, I realized that what we always did was quick shot after quick shot, one after the other. At that time, I wanted to have a long shot that would grasp this particular moment. It is when the crew is tired the hell out of everything, everyone is a bit lost, out of the frame, on their way to somewhere shortly before it finally finishes. So when that happens on the real set, I thought I wanted to convey that in the film as well. It came with the moment. And I wanted to recreate it. Only through that I could finally grasp what it feels like to finish such a film and tell about this moment to the audience. It almost worked as a documentary in which we could record everything naturally like it wasn't a film, but real life. With that being said, I also do not pre-setup anything before shooting. I always try to be creative onset. No matter what film I do, whether it is a hard or an easy one. Being right here and right now is the most inspirational for me.

What about the film critic present in one of the scenes? Are film critics in China really called eunuchs? It's a fantastic scene, by the way.

(laughs) It's all because of the internet environment. Everybody can become a critic these days. Anyone can spread their critique on the internet across the world. That can be advantageous, but at the same time, very harmful. For instance, many websites related to the food industry, like YELP, use this mechanism. If you want to rate the restaurant, you can simply do it there. People can like or dislike, put some comments. Everybody can do the reviews. Before you go to the restaurant, you see if there are good opinions or not to get an idea of the value of each of the venues.

And now back to the story. The thing is that film critics are the bridge between the film and the audience. If someone wants to watch the film, they can read the critic's opinion about it, or the comments on some websites, to get the basic idea of its quality. It is how it works, and there is nothing unusual about it these days. What I don't agree with, is the aspect of paying the critic for writing a positive review. It's not film criticism then, it's e-commerce. It prevents the audience from having a clear environment to understand the film on their own. That's simply disrespectful.

With “Ripples of Life” you also manage to create a Chinese social landscape. Was there a need to address any specific place, any specific story?

In the script, I initially addressed a specific city, but eventually, it became just a city, not a specific one, but one of the many in China. Instead of focusing on something specific, I rather wanted to depict certain social strata. Among the characters, we can find many middle-aged people in contrast to youth, and everything is set in a very small town, where nothing ever happens. For example, in the first story, Xiaogu dreams about escaping to a bigger city, to a different life. In the second story, the famous actress Chen Chen, even though she stays in the big city, for some reason she longs for her hometown and small city life. She misses peace. And what I meant by that is that people and their desires vary from each other. There are different perspectives on the big city life for those who stay in the small town and vice versa – one does simply not get the whole picture from their standpoint.