Biopics of historically important national figures are a tricky business. Include little information about them and you run the risk of the wider international audience not understanding enough to be engaged in the story. Include too much information and you end up making the feature a lengthy history lesson with lesser entertainment value. Director Lee Joon-ik, a man quite well versed in the historical genre, managed to make one of the better biopics in recent time on one such figure that is widely known of in Korea but a relatively unknown figure internationally in “Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet”. After a brief stint with urban storytelling in “Sunset in My Hometown”, the director of such hit historicals as “The Throne” and “The King and the Clown” is back once again with another story of a figure who is less spoken of even in Korea.

“The Book of Fish” is screening at New York Asian Film Festival

“The Book of Fish” begins at the death of King Jeongjo, following which child King Sunjo ascends the throne and the dowager Queen becomes the defacto ruler of Joseon. Among her first rulings is to launch an attack on the Catholics, the followers of the so-called western evil, who are declared traitors of the nation and Confucian ideologies. Chief among those are the Jeong family, consisting of brothers Jeong Yak-jong, Jeong Yak-jeon and Jeon Yak-yong. While Yak-jong is killed, the other two brothers are exiled in far-off places, with Yak-jeon being sent to the remote Black Mountain Island.

There, Yak-jeon is taken in by a kindly widow, who respects his noble, high ranking position and he also comes across local fisherman Jang Chang-dae, the most well-read on the island who has an unusually vast knowledge of marine creatures and plants. Chang-dae dreams of studying far more and getting a reputable job within the government, but the lack of books and a teacher stops him. For him, Yak-jeon should be an opportune arrival but Chang-dae considers him a traitor to the throne and to Confucian doctrines. However, when Yak-jeon, most impressed by the fisherman's marine knowledge, decides to write an encyclopaedia on the marine life around Black Mountain Island, the two realise they could be mutually beneficial to each other and a teacher and student bond soon begins to develop.

Lee Joon-ik's choice of subject matter is most interesting this time round. Most storytellers would probably choose to tell the tale of Jeon Yak-yong, one of the greatest scholars, poets and thinkers of Joseon and certainly a man with an eventful life himself. Lee, however, chooses his elder brother and a man with comparatively fewer but no less important works, a man who history since seems to have neglected and how he came to write his magnum opus, The Book of Fish. Through this, Lee also tells the story of class and rank in the Joseon era and how vastly that affected careers and lives. He is also most interested in both the good and bad sides of Confucianism, a topic still relevant in modern Korean society.

It's ironic that the director had to return to a historical, his strongest suit, after the lukewarm modern production that his previous film was, because change is a constant and the biggest theme throughout this narrative. The acceptance of change is highlighted by Yak-jeon's character, who has, unlike what others would make it out to be, not completely denounced Confucian ways but is willing to accept and address its shortcomings and also accepted the new faith from the West. The reluctance of taking change on is personified in Chang-dae, who wants to succeed in life but is reluctant to take on change that clearly would benefit him. It was also when Yak-jeon changed direction from writing poetry, stories and treaties that he went on to write his now most famous work. The pursuit of change, and the repercussions of accepting it, also play heavy on Chang-dae's arc in the third act.

If the first act focuses on setting up Yak-jeon's story and the second on establishing the relationship between the teacher and his student, this third act slows up as the two go in different directions. Here, the narrative derails a bit and while it still takes turns to focus on the two characters and particularly bears heavy on Chang-dae's journey, the time jump feels disjointed and an avoidable extension of the runtime. A clearer explanation of whether Chang-dae is indeed a real historical figure would have also been appreciated by the uninitiated. On the plus side, at least that means more scenes of an on-form Byun Yo-han, whose Jang Chang-dae goes through a long journey as a character, all of which is portrayed convincingly by Byun. The conviction he shows on his face is of a man wanting to do better, be better but is dealt the wrong hand in life finally getting something go his way.

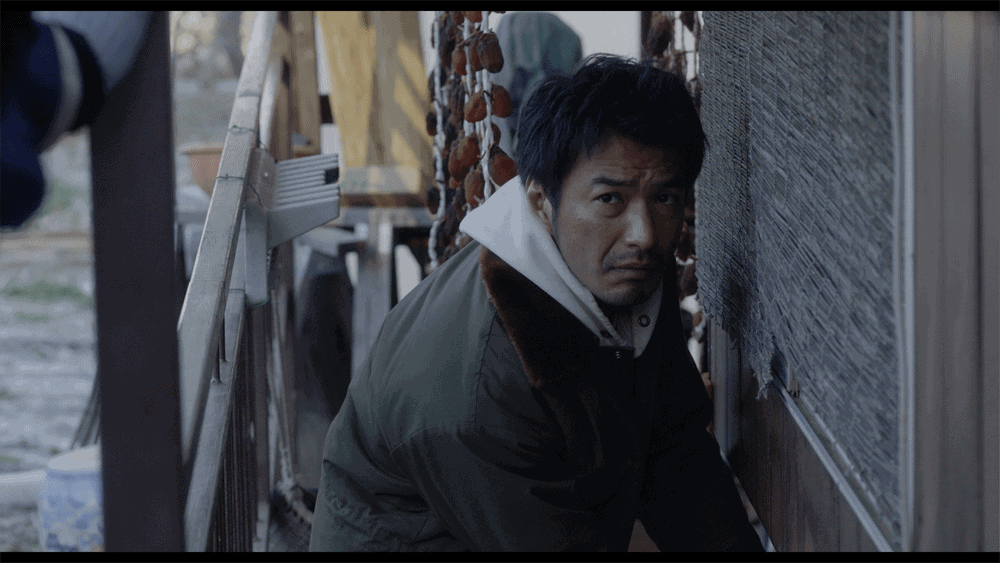

Sol Kyung-gu is an absolute chameleon of an actor and he immerses himself into Yak-jeon, an about-turn from his previous works yet nonetheless impactful. His very first historical and his second collaboration with Lee Joon-ik after “Hope”, he carries the nobility required for the role with effortless ease. The curiosity he shows for the marine life is almost infectious, while also keeping an aura of solemnity around the character throughout. The combination of joy and sorrow that he seems to convey purely with his eyes and body language when he hears of the end of his brother's exile is something only a seasoned actor of his calibre can portray. Lee Jung-eun is her usual cheerful self as the widow from Gageo while Jo Woo-jin brings the laughs the Black Mountain Island Consul. The two big-name cameos, one reprising the role of the King from an earlier Lee Joon-ik film and the other lending his iconic voice to the character and poetry of Jeong Yak-yong, are welcome surprises.

But “The Book of Fish” will most likely be long remembered for its stunning visuals. Entirely in black-and-white like Lee's previous work “Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet”, it opens with a scene of a boat afloat in the sun-drenched sea and Lee Eui-tae's cinematography rarely lets up in visual beauty. Monochrome scenes of fog-covered mountains, waves crashing on shores, fishing in the water all look almost straight out of a Chinese watercolour painting, much like Zhang Yimou's “Shadow”. While this production is not as elaborate with its set designing and costumes to compliment the cinematography like Zhang's film was, it is nevertheless impressive in those departments too. The written poetry that comes up on the screen when either Yaj-jeon or Yak-yong recite some of their famous works further enhances the painting-like effect of the imagery, the words sounding almost hypnotic in the voice of Sol Kyung-gu and the star that plays Yak-yong.

Visually memorable, competently acted and a historical biopic with both sufficient information and entertainment values, “The Book of Fish” is easily among Lee Joon-ik's best works, and that says something considering his rich filmography. If only it was not marred down by an inconsistent final act, it could very well have competed with the likes of “The King and the Clown” or “The Throne” for the top spot in his oeuvre.