Carlo Francisco Manatad (born October 4, 1987,Tacloban City) is a Filipino film director and editor based in Manila. He is a graduate of the University of the Philippines Film Institute. His short film, “Junilyn Has”, competed at the Festival del film Locarno and went on to screen at several international film festivals such as Clermont Ferrand, Uppsala, Winterthur and Busan to name a few. “Sandra and Fatima Marie Torres and the Invasion of Space Shuttle Pinas 25” has won awards in Russia, Romania and the USA, most notably winning the Best Comedy Short at the Aspenshorts Fest – an Oscar qualifying film festival. A Philippine and Singaporean co-production, “Jodilerks Dela Cruz, Employee of the Month”, his last short film was selected in competition at the 56th Semaine de la Critique at the 70th Cannes International Film Festival. One of the most prolific editors in the Philippines today, he has collaborated with numerous filmmakers for independent and mainstream scene. Manatad is also an alumnus of the Asian Film Academy, the Berlinale Talent Campus, and the Docnet Campus Project.

Charo Santos-Concio is a Filipina media executive and actress. She is the host of Maalaala Mo Kaya, the longest-running television drama anthology in Asia. From 2012 to 2016, she was the chief executive officer of ABS-CBN Corporation, the largest entertainment and media conglomerate in the Philippines. In the 1980s, Santos-Concio produced a number of films such as Oro, Plata, Mata and Himala under the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines. She also served as the creative force behind the productions of Vanguard Films and Vision Films before moving to Regal Films. She established herself as an award-winning dramatic actress early in her career, winning the trophy for her performance in Mike de Leon's Itim during the 1977 Asian Film Festival. She was critically acclaimed for her performance in Lino Brocka's 1990 film Gumapang Ka Sa Lusak which won several awards including a Best Director FAMAS for Brocka. On December 26, 2007, the Film Academy of the Philippines (FAP) awarded Santos-Concio with the Manuel de Leon Award for her work in the industry.[

Armi Rae Cacanindin is a Filipina producer based in Manila. She has received funding for her feature films from highly competitive grants such as Aide aux Cinema du Monde, World Cinema Fund, Sundance Film Institute grant, IDFA Bertha Fund, Doha Film Institute post grant, Purin Pictures grant, Asian Cinema Fund, Hubert Bals Fund, Vision Sud Est, Torino Film Lab, SGIFF'S SEA-DOC fund and the recently launched ICOF and ACOF by the Film Development Council of the Philippines.An alumna of Busan's Asian Film Academy, Berlinale Talents, Talents Tokyo and IDFAcademy she has pitched projects at La Fabrique des Cinema du Monde, TorinoFilmLab, Cannes Cinefondation's L'Atelier, IDFA Forum and Hongkong Asian Film Financing Forum. Her credits include films like “EDSA XXX: Nothing Ever Changes in the Ever-Changing Republic of Ek-Ek-Ek”, “Nervous Translation”, “Aswang”, and “Fan Girl”.

Growing up in Singapore's multiracial and multicultural environment has shaped Teck Siang Lim‘s interest in collaborating across cultures, and he has worked on cross-border projects around the world. His approach to narrative cinematography is grounded in storytelling craft, while seeking a balance between poetry, emotion and technical precision. He is a graduate in Cinematography from the American Film Institute in Los Angeles.

On the occasion of “Whether the Weather is Fine” screening in Locarno, where it also won the Junior Jury Award, we speak with Carlo Francisco Manatad, Armi Rae Cacanindin, Teck Siang Lim and Charo Santos-Concio regarding the production of the movie, principal photography and the impressive visuals, acting in the film, religion, absurdity, avoiding “misery porn”, and many other topics.

Can you give us some details about the production of the film?

Armi Rae Cacanindin: “Whether the Weather is Fine”/”Kun Maupay Man It Panahon” took seven years in the making. There was a long period of time we spent in the development of the script, and also in the development of Carlo as a director.

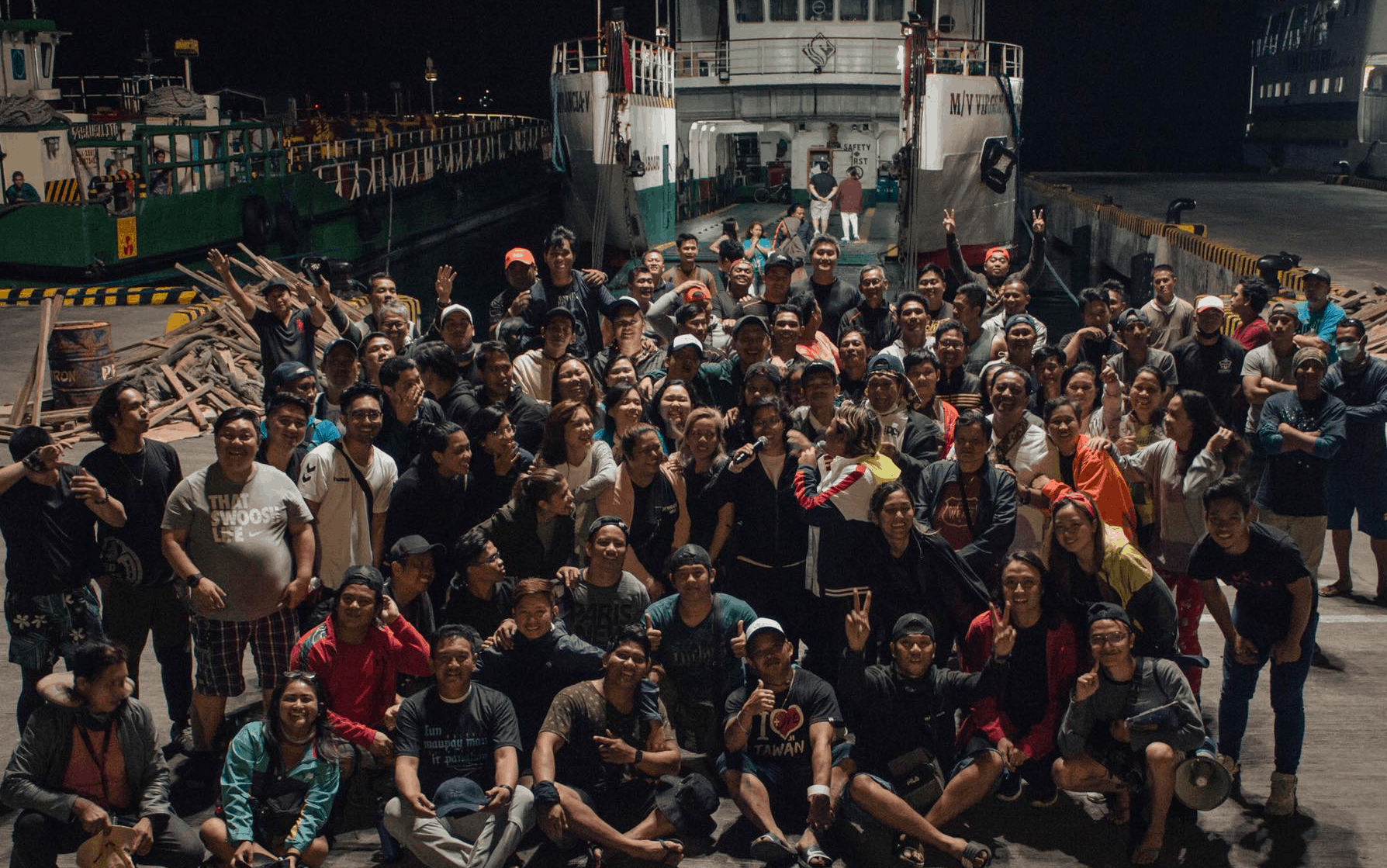

While going through different film labs and markets to find partners and funding, we made two more shorts to prepare him for this big production. Let's admit it, “Whether the Weather is Fine” could be the biggest first feature in the history of PH cinema, and I needed him to be prepared for that, not just vision-wise but also on how to deal with 800 background extras, or how to execute the widest shot of the devastation, VFX-wise and art direction-wise, or how to deal with the biggest celebrity actor in the PH that is Daniel Padilla, and veteran actress/network executive that is Ms. Charo Santos.

Looking in hindsight, the years we spent preparing Carlo paid well, as you can see in the finished film. The way he collaborated with the department heads and his actors is evident in every frame. It also helped a lot that there was more time during last year to pause, take a back seat while editing and assess/reassess.

With all these things happening in the span of seven years – different film labs with different tutors, international funding applications, big named actors, enormous set requirements and the pandemic hitting the entire world – one thing did not change. It was Carlo's reasons for making this film: he wants this to be his love song for his hometown. With all these, we always come back to that intention.

Can you give us some details about the principal photography?

Armi Rae Cacanindin: We shot for total of 19 days, from December to February, in different parts of the Philippines, mostly nearby Manila. We flew to Tacloban to shoot for 4 days, mostly in the Tacloban Convention Center where the dancing and the relief center scenes happened, since that is the most iconic landmark in Tacloban. We shot the ending of Miguel, the last scene, even if Daniel was not feeling very well at the time, and good thing we did finish, before the COVID situation worsened in the Philippines and the rest of the world. Scenes with hundreds of extras, like what we have in the film, are not safe to do right now and maybe in the next 3 years!

Carlo Francisco Manatad: With the constraints in logistics and budget, we had to shoot and recreate a lot of scenes in the northern part of the Philippines. I, as the director understood the situation but we pushed hard to have key scenes be shot in my hometown. Key scenes that would make the film more authentic. But more than anything, as a film set in my hometown, I wanted it to emit a feeling of going back, not reliving the experience, but capturing, in a way, this memory of resiliency.

The cinematography and the various sets the movie takes place in are among the best parts of the film. Can you give me some details about your approach towards the visuals of the film and the way you manages to come up with all those impressive images?

Teck Siang Lim: Over the course of developing the visual language for the film, Carlo, Whammy Alcazaren and I reviewed many photography references from the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in Tacloban. There was an abundance of documentation and several images stood out, mostly taken through the eyes of photographers Philippe Lopez (AFP), Chris McGrath and Nic Bothma, whose images focused on situations similar to our script and visual language. These images portrayed moments of surrealism, absurdness and strangeness that unfolded amongst the madness of death, desperation and destruction, and reflected the recollections that Carlo had from his experiences of the aftermath of the typhoon, during which the roles of adults, children and animals were upended.

The photographs also gave me insight into the environment, e.g., the weather conditions after the typhoon, the sources of light at night when electricity was not available, and the haunting beauty of the skies and sunlight as a backdrop to the horrific destruction.

Working with Production Designer Whammy was a blessing. He paid careful attention to every detail, right down to the arrangement of the colors of every prop in a location or set – yet it felt natural and organic. I took a naturalistic approach to composition and lighting approach that complimented the environment he created in order to create a space that was real and comfortable for our actors.

Carlo did not want to make a film that was only about the disaster, but to focus on the relationships between the main characters as well. This was the driving factor for picking the 1.33:1 aspect ratio for the film. The vertically driven format allowed us to keep the emphasis on our screen characters and less on the environment.

Carlo Francisco Manatad: It was a very fun but tedious collaboration with Teck and Whammy, both of which have been on board since the conception of the film. Because we shot years after the storm, we had to build everything from scratch. Our inspiration was recreating and, at least to some point, making it look as authentic as possible by basing it on the photos from the real aftermath of the harrowing typhoon. The mix of the real and absurd was implemented cleverly to create this sort of believable but, more importantly, whimsical world. The lighting setup was minimal but implemented strategically; almost all exterior scenes were shot naturally.

More than anything, not just the visuals, but the whole shape of the film is the result of mutual understanding among all those who collaborated

The film could easily be a genuine drama of the “misery porn” quality, considering its base material but you chose a completely different approach, filled with humor, surrealism and social-political commentary. Why did you choose this approach, and how close to your experience of the events is the whole story?

Carlo Francisco Manatad: Usually, tragic films are melodramatic and people tend to cling to that cliche. However, I wanted “Whether the Weather is Fine” to be presented in a different light, unlike how people would expect it to be, mainly by making no effort to push forward a storytelling so precise but also so raw and playful. I just wanted this very specific, culturally, story to be universal. And yes, it is loosely inspired by my experiences and, at the end of the day, authenticity matters.

In the film, there are recurring images of children appearing from nowhere on occasion. Why did you decide to include that and where did you find all these children? How was your cooperation with them?

Carlo Francisco Manatad: The children were all locals. And there were no requirements to begin with. I just wanted them to act as themselves. I did not want to not put restraint in this innocence and punkness. Furthermore, on a bigger scope, from what I observed during those tragic moments, the children appear more grounded to a certain extent, they are more “mature” than the grown ups in terms of their approach, and I also wanted to show this aspect in the movie.

Religion seems to be a part of the movie, but also of Filipino society. Can you tell me a bit more about this concept and the way it was implemented in the film?

Carlo Francisco Manatad: In general, Filipinos are dominated by Catholicism, as am I. However, I have a more critical approach regarding how religion affects not just to me but society as a whole. It is not criticism but a mere observation on the realities Catholicism promotes, especially in times of despair, because, along with tragedy, hoping and believing in something higher also appear. Religion becomes a currency, almost. You believe in something because you feel it will make you feel better, you talk to someone that's not physically present but is always there. But it really does something, in the way it affects the psyche. However, it is also a question I ask everyday, and largely, the main reason I wanted to expound on these concepts.

Do you feel that absurdity (as in the case of suddenly starting dancing while the whole world is crumbling around you) is a coping mechanism for the tragedies people experience?

This scene was actually based on a real event I experienced and witnessed. It may look absurd or weird or even senseless to a point. But I felt it was, one way or another – a point where people just start doing something else rather than think of their current situation, which is essentially their way of moving forward with the situation they have just faced.

Why did you choose to act this part, and how would you describe your character in general? The violent scene is one of the most powerful in the film. Can you tell me about how you approached the particular scene?

Charo Santos-Concio: As soon as I read the script, I was drawn to the character of Norma, a woman teetering between survival and despair, set in the aftermath of typhoon Yolanda. I like to portray characters who are not afraid to show their vulnerability and are multi-dimensional. I was also very much challenged that the entire script was written in Waray, a dialect in Tacloban, Eastern Visayas part of the Philippines. It sharpens your brain.

The violent scene is the most grueling part of the film. Not only was it physically exhausting….We had the rain effect and were walking along puddles of muddy water. It was also a heart-wrenching and painful moment between mother and son. This is the part where Norma begins to sink into desperation. It was my “wish I were dead” scene. Daniel Padilla and I had to talk prior the shoot and rehearsed the movements several times. Daniel was respectful and careful and very professional . I really looked forward to working with this young icon, Daniel Padilla, who has proven yet again in this film, his brilliance and versatility.

There are a few scenes where Rans Rifol is singing. Is she actually singing in those and why did you decide to include them in the film?

I always had this penchant for performances, may it be singing or dancing. On a Filipino context, we take pride of these performers, and it is something that is ingrained in our way of thinking. Everything stops when someone performs. This was also the main reason Rans Rifol was cast, because she is also a performer. And also someone I saw had the potential and rawness to play such a complicated character as Andrea.

Mainly also the reason why Rans was casted because she was also a performer. And also someone that I saw that had this potential and rawness to play this. Complicated character , that is Andrea.

What is your opinion of the Filipino industry at the moment?

Armi Rae Cacanindin: Cinemas in the Philippines have remained closed since the first lock-down. We release films digitally now, but the main problem is piracy.

Carlo Francisco Manatad: The pandemic has not only lessened the number of productions but also took away (at least temporarily) a lot of jobs from film workers. However, more than anything, the resiliency still stands. The industry is continuously struggling but it is also thriving, growing. It is amazing. Haha