By Ksenia Isakova

One of the film's other messages seems to be that life also is too complicated to live under the harsh light of moral purity (Patrick Brzeski in the interview with Chung Mong-Hong about his movie “A Sun” for The Hollywood Reporter).

As time goes by, little by little we might forget about lots of details about a particular movie: the intricacies of the story development, setting nuances, even the director's name or a movie title. However, certain stable and repeated patterns such as Maggie Cheung's cheongsams in Wong Kar-wai's “In the Mood for Love,” the impeccable and haunting sound effects of Kiyoshi Kurosawa's “Pulse”, or the vision of the serene yet frightening fields of “Memories of the Murder” by Bong Joon-ho, are probably there to stay with us in our memory for much longer. These are the elements of mise-en-scene, and as Bordwell and Thompson rightfully suggest, this is what the viewers would more likely take a note of (112).

This article is part of the Asian Cinema Education Film Criticism Course 2021

The distinct feature that shines out in Edward Yang's “The Terrorizers” (1986) in terms of its mise-en-scene is the work with light. At first, one may instantly notice that lighting sources and techniques used in this movie are very nuanced and diverse: highlights and shadows, hard and soft light, frontal lighting, back- and side-lighting[1]; additionally, lighting colors vary between the scenes a lot. As viewers, we may ask: why does the approach towards the lighting in the film stand out so much? Is there any implicit or symbolic meaning regarding the ways characters interact with sources of light? While traditionally “The Terrorizers” receive attention as a movie with a complex character network (Gilman), I believe that it might be beneficial to review the characters separately in terms of the lighting treatment they receive.

To establish the context for the answer to the mentioned inquiry, we may take a look at another much more recent Taiwanese movie, “A Sun” (2019) that may shed light on the way the lighting functions in Edward Yang's movie. In Chung Mong-hong's movie, sunlight operates as a device that serves more than just an aesthetic function. It stands for reason, order, and norms. It is the inability to escape the pressure of the sun that leads one of the characters towards the tragic end. Similarly, Edward Yang's movie can be also seen as a precautionary tale about one's relations with the light.

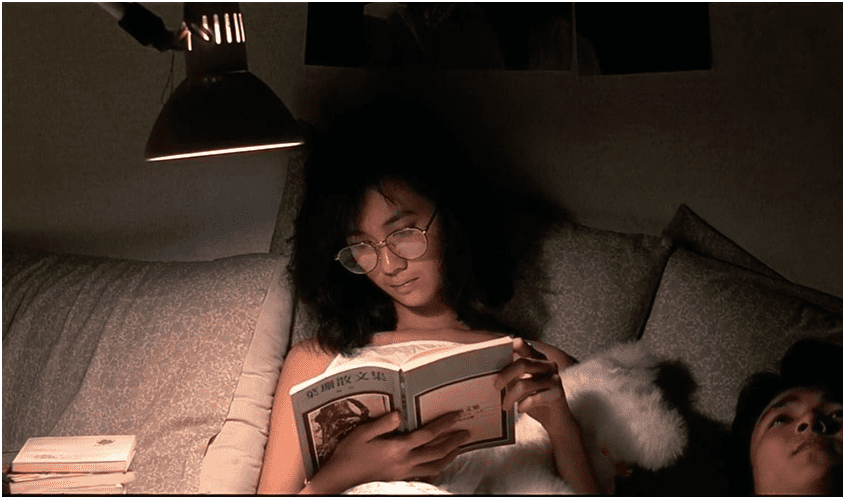

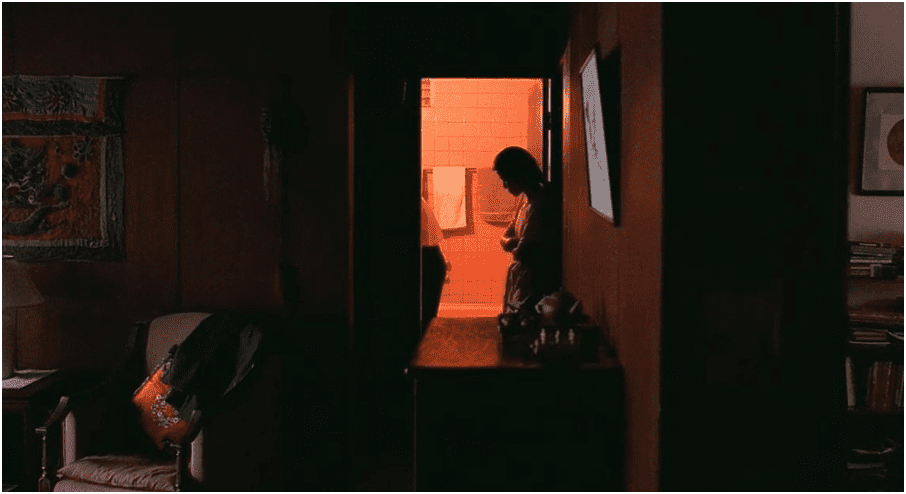

However, here is where a significant difference between the two movies arises. While focusing on the male perspective, we can see women in “A Sun” only in traditional Confucian roles: a mother or a girlfriend. In his turn, Edward Yang provides female characters with more profound agency[2]. As a result, every character, including the female ones, have their own interplay with the light. For example, in the picture below, the writer is secretly smoking under a dim and soft light: she has her privacy and space to reflect on her life, desires, ambitions. She feels comfortable with her secret and her thoughts, no need to withstand or endure. That is why in this essay we are focusing on male characters exclusively – the photographer and the doctor, who unlike their female counterparts in “The Terrorizers”, exhibit problematic relationships with the light.

As for the younger male character, the photographer, his storyline undergoes a cycle: he once tries to escape from the light but eventually, to come back to it. However, his initial discomfort with the light, both literally and figuratively, is quite strong, which we can notice in the opening scene. Here, the sun is rising, and the photographer implies annoyingly his concern about the light being on the whole night, as his girlfriend was reading. Although the light is directed on her face, we can notice him lying restlessly in the backlight: there is too much brightness in his life.

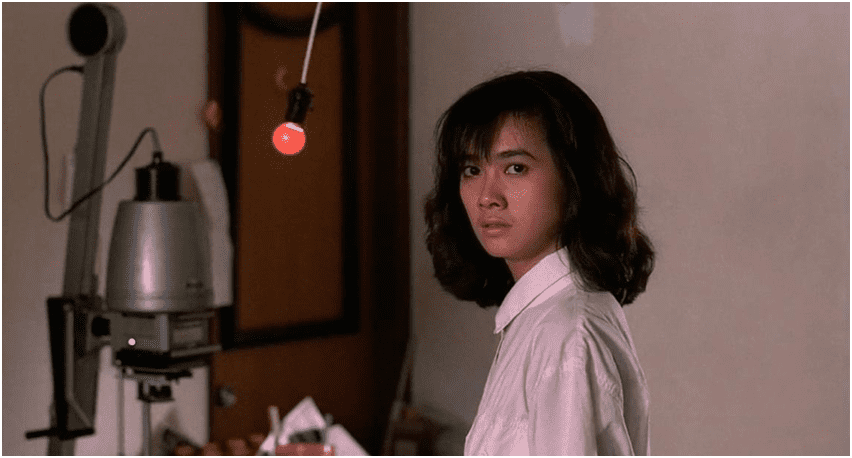

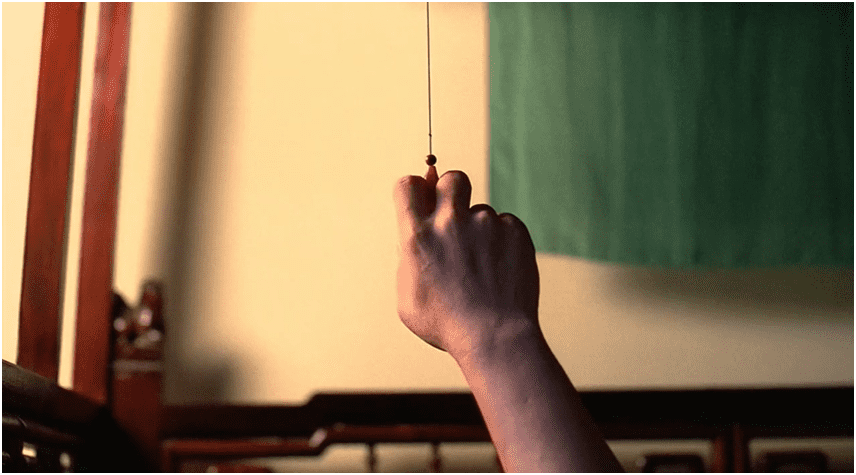

However, the photography, his hobby that helps him to escape the light, leads to a relationship crisis with the said girlfriend after she finds the pictures of the White Chick, the ‘exotic' girl he once took too many photos of. During the conflict, the girlfriend brings all his life to the sunlight as she tears down the black curtains and destroys the undeveloped film by exposing it to the light. When she looks back at him angrily, the pressure he experiences is emphasized with the help of the shaking darkroom red lamp. The exposure to the light and the reasoning it represents motivates him to rent a room that happens to be the crime scene, from which the Eurasian girl fled. Here, the character takes a radical step towards leaving the light pressures behind.

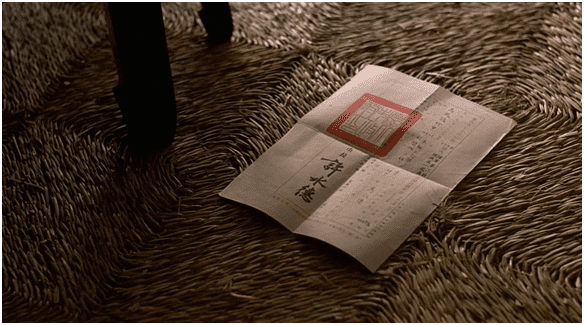

In his newfound place of refuge, the photographer seems to find peace for a while by covering the big window with black sheets. Still, the metaphorical light finds its way to the character in a form of his father's reluctance to support him financially in his artistic endeavors, as well as the army draft that he receives. Nonetheless, on his apartment's wall, the photographer arranges a big collage of the White Chick image that may represent his temptation towards another way of living not dictated by his father or sociocultural norms. Eventually, his dream girl visits him due to a puzzling chain of narration of “The Terrorizers”, only to make the photographer face the harsh reality of his illusion when she almost steals his cameras. In a short while, he tears down the cover from his window – to finally face the light.

He goes back to the father's house, accepts the army draft notice, and makes up with his girlfriend. Will he be happy? His neglect towards the draft notice may say otherwise. Still, he is on his way to be a filial son, a devoted husband, and an obedient and righteous citizen.

While the photographer seems to be on his way to find peace with the need to accept the duties the light represents, another crucial male character, a hospital professional Li Lizhong, never learns how to hide from it. Quite possibly, there is a chance to interpret the way his character's story arc develops as a warning sign not to take ‘the light' too seriously. Can it be the reason why the doctor's story has such a tragic end?

Indeed, in every scene the doctor appears, he is always visible to others, and this setup reflects how he navigates and interprets his own and his wife's lives. While the photographer is trying to find himself, Li Lizhong follows strictly defined guidelines. In his worldview, career is the top priority for a man. In his understanding, his wife needs to be surrounded by nice things, and her miscarriage, meaning the failed motherhood, is what makes her unhappy. And yet, he, often quite literally, is unable to see her clearly, in the daylight. For example, in the scene when he comes back from work after he threw his friend under the bus to have a chance to become a lab manager, he goes directly to the well-lit bathroom, all exposed, while his wife reaches him from the semi-darkness and stays there. The bathroom light, a saturated orange, hints the pressure of his status and ambitions he cannot escape.

In a similar way, the night after he talks to his about-to-be-resigned friend, we see him lying in the dark alone. However, immediately he turns on the light and stares right at it as if he fails to privately reflect on what happened and what it means to him.

This character is searching for a ‘lighting' companion even in such a private matter as the divorce talk. In this scene, the way the room is lit with soft light keeps the wife hidden from the viewers, but he is still exposed. Above them is the lamp of a nearly perfect round shape as if to mirror the need for reason and logic. He tries to control the situation, to fix it. However, the wife has another chaotic yet liberating mindset: every failure is a new beginning, and she applies it to their marriage too.

Whereas the photographer's arc is cyclic (he goes away, then returns, probably to experience the urge for escapism again), the doctor's rigorous path under the constant light stops at a dead-end. In his final scene, he reflects on a possible scenario of taking on everyone who is at fault for his marital failure, White Chick included. However, this would not mean his life getting to the respectful scenario he dreamed of. This is the first and the last time we see him before his death alone reflecting on what is happening. Nonetheless, even in the end he is never in a shadow: the morning light is harsh and unavoidable. Even in his death, he is unable to escape the light.

When “The Terrorizers” got their international wide release in 2015, Japan Times pointed out that, in the movie, the Taiwanese are preoccupied with the need to succeed, and the societal pressure makes them anxious and alienated, which might have been a reality back then (Shoji). However, it seems that the implicit message of the movie remains relevant today. Edward Yang used light to emphasize the societal norms and the pressure they produce to warn about possible consequences they may bring for us, unless we don't find our ways to ignore them at least for a while. The work with light in “The Terrorizers” creates disposition, explains, and guides the characters through their storylines, and for the male characters the harsh and piercing light of social norms and rules appears to be especially stressful.

Works Cited

Brzeski, Patrick. “Taiwan'S Chung Mong-Hong On His Epic Oscar Hopeful ‘A Sun' – The Hollywood Reporter”. The Hollywood Reporter, 2021, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/taiwans-chung-mong-hong-on-his-epic-oscar-hopeful-a-sun-4125960/.

Chang, Kai-Man. “Filming Critical Female Perspectives: Edward Yang'S The Terrorizers”. ASIANetwork Exchange A Journal For Asian Studies In The Liberal Arts, vol 24, no. 1, 2017, pp. 112-131. Open Library Of The Humanities, https://doi.org/10.16995/ane.157. Accessed 15 Oct 2021.

Gilman, Sean. “Taiwan Stories: The New Cinema Of The 1980S”. MUBI, 2020, https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/taiwan-stories-the-new-cinema-of-the-1980s.

Shoji, Kaori. “The Terrorizers: ‘A Masterpiece About Taiwan Under The Influence Of Money And Globalization'”. The Japan Times, 2015, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2015/03/11/films/film-reviews/terrorizers-masterpiece-taiwan-influence-money-globalization/.

[1] Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. Film Art. Mcgraw Hill, 2010.

[2] In his article “Filming Critical Female Perspectives: Edward Yang's The Terrorizers, Kai Man-Chang underlines that Edward Yang uses female characters to “criticize the impact of neoliberal capitalism in Taipei”.