by Marlene Langbein

On paper, “Shoplifters” by Hirokazu Koreeda, who also wrote and edited the film, seems sad, dark and depressing. However, the Japanese director manages to wrap the topics of poverty, crime and neglect in a blanket of happiness. This movie is a surprisingly heart-warming and joyful examination of unlikely family bonds. Most importantly, he achieves this with gentle nuance and without downplaying the serious context of crime and poverty – achieving a striking balance between telling a sad story but doing so in a happy way. How did he do it? Why is “Shoplifters” not sadder?

This article is part of the Asian Cinema Education Film Criticism Course 2021

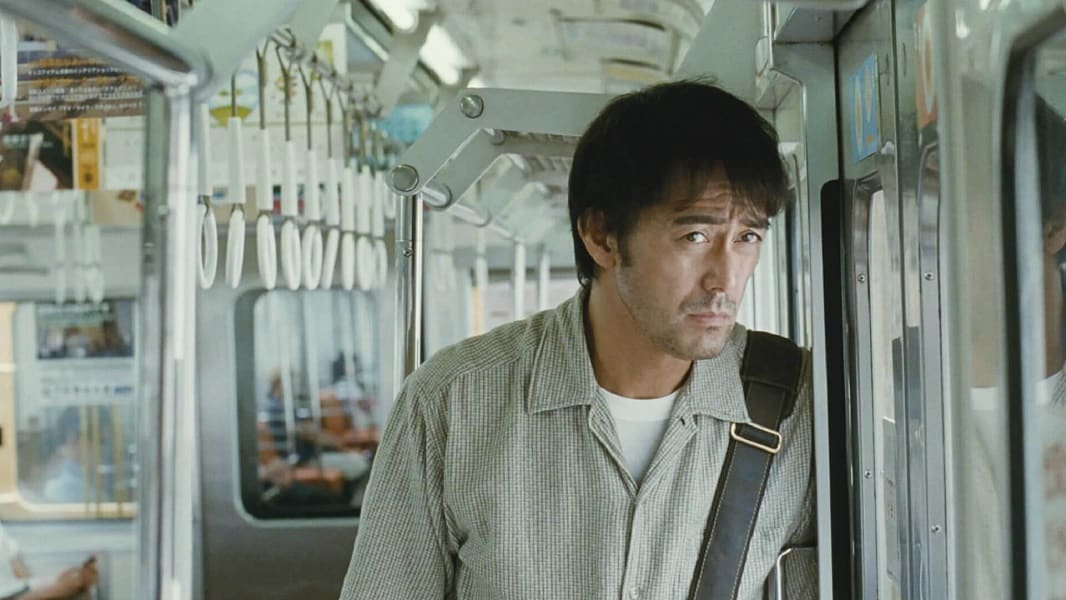

“Shoplifters” is a crime drama from 2018 about a family of misfits who are not related by blood, but still grow together anyway. We see Osamu, the father, Nobuyo, the mother, Hatsue, the grandmother, Aki the young woman and the children Yuri and Shota living in poverty and shoplifting to survive. Yuri was abused and neglected before she joined them, Aki deals with self-harm, Shota does not go to school and takes his big backpack everywhere to make ramen noodles disappear from convenience stores. Nevertheless, Koreeda and his collaborators used the writing, directing, lighting and costume design to wrap all of this misery in a warm and cosy mood, full of love and joy. This essay will examine his methods and attempt to evaluate if the movie successfully deals with a heavy topic in a cheerful way.

Koreeda's first method becomes apparent when analysing the film and broadly categorizing each scene into “happy”, “sad” or “mixed”. It would seem that, in a movie about crime and poverty, most scenes should be sad, but the majority are actually happy and quite a few are both. Most “sad” scenes are grouped in the end, when the characters face consequences for their actions. It becomes clear that the mixed scenes are where he gently brings nuance to the film. He aligns his writing and directing to create “mixed messages” that are cheerful and warm, but which also include a small detail that throws the mood off slightly. Each “mixed message” scene is like a small rain cloud in the sunny sky. This allows him to make a happy movie about a heavy subject.

One scene in the middle of the movie makes this tactic very visible: All family members are coming home for dinner at the end of the day. We see the women in the kitchen, cooking and chatting about men. At the same time, Osamu is showing the children a magic trick in the living room. The mood of the scene is cheerful, relaxed, intimate and harmonious. The family is at the height of their closeness. We switch between the kitchen and the living room but keep hearing voices from the other room in the background. This feels close, intimate and warm. Everything about the scene looks so normal, it seems like they are actually turning into a traditional family. Then, the little rain cloud comes in: In the middle of cheerful magic tricks, Shota tells Osamu that a shopkeeper caught them stealing and warned Shota not to teach his sister to shoplift. Shota is troubled by this and is starting to sense the moral ambiguity of the family's lifestyle. Osamu, however, brushes the comment off by saying that “she is too young anyway”. We watch Shota feel misunderstood and conflicted while Osamu walks away. It is a short exchange, only a few sentences and a fraction of the entire scene. Not quite enough to upset the good mood overall, but enough to start an itch in our mind.

The writing in this scene is not the only tool Koreeda uses to make these rain clouds: his directing and the performance of the actors play a big role in the subtlety. Jyo Kairi as Shota and Lily Franky as Osamu play this very nonchalant and neutral, as if their exchange is no big deal. Especially, Lily Frank's performance feels dorky and boyish, which balances out a lot of seriousness. They could have employed a more serious tone of voice, more aggressive gestures or tense facial expressions. Kore-eda could have given them more dialogue to discuss the event with the shopkeeper. Instead, their restrained, gentle storytelling does not leave the audience pondering on the moral implication of the scene. The focus remains on the warm, cosy family life and their growing bond.

Clearly, the writing and directing have a big effect on the overall focus of a film. However, the lighting, and especially its colour, plays an equally important role in setting the cheerful mood. The movie's colour palette is very warm and that is mainly due to the lighting. Cinematographer Ryuto Kondo lights all family scenes in cosy, yellow light with few shadows. It looks like natural light on a sunny day through a yellowed window. This gives the movie a very warm and comfortable overall mood. Only when a family member feels sad, he switches to more blue, gloomy, artificial light from above, which throws dark shadows over their faces.

This colour choice appears even more intentional when considering that yellow, orange and gold are very positive symbols in Japan. The colour yellow represents nature, sunshine and the sacred. Orange stands for love and happiness. Gold suggests wealth and prestige. All associations connect well with the film's musings on family bonds, love and human desire.

Interestingly, only three scenes are lit in sickly, saturated neon yellow: the three interrogation scenes where Osamu, Nobuyo and Aki are confronted with the harsh judgement of the real world, in the form of police and childcare services. The telling lines “Grandma didn't want me?”, “Why did you name Shota after yourself?” and “You can not be a mother without giving birth?” are all uttered while Aki, Osamu and Nobuyo are drenched in the sickly yellow light of treachery. We have seen them bathed in yellow sunlight at their most happy family moments and now, when reality hits and the adults are judged for their actions, the happy, healthy family colour has turned sickly.

The colour yellow is a double agent in this film, as it creates the overall cosy mood but also turns bad on the characters in these crucial scenes, while simultaneously reminding the viewer of the happy times they are judged for. Kore-eda and Kondô masterfully use light and colour to balance the overall cheerful mood of the story with nuanced considerations on the serious subject.

One last set of choices can further explain how Koreeda achieved the dissonance in mood and subject: the costume design by Kazuko Kurosawa. She dressed all family members, especially Osamu and Nobuyo, in cosy, comfortable clothing in primary colours or colourful patterns. The pieces are made from organic materials like cotton or wool. Usually, crime dramas would suggest polyester and leather which give a more cold, uncomfortable energy. One might also expect more muted colours, blacks and greys. Instead, the characters wear saturated yellows, reds and blues or colourful patterns with flower motives. The clothing does not look neglected and shabby – we even see the grandma mending clothes at some point. These choices treat the subject of poverty with gentle nuance, without extreme drama or exaggeration. Together with the warm lighting, they create the cosy family atmosphere of the film, without neglecting the serious subject of it.

So, why is “Shoplifters” not sadder? The biggest impact comes from the “mixed messages” that Koreeda wrote into the scenes. They give space to the serious undertones without turning the mood sour. Together with the cinematographer and costume designer, he creates a warm stage for a movie about family bonds that are forged in an objectively dark situation. One last question worth asking is if “Shoplifters” should have been sadder to give serious topics like poverty the attention they deserve. There is a danger of focusing too much on the positives, and a movie might start to appear naive or superficial.

First, given Koreeda's affinity with the topic of family in past works, such as “Still Walking” and “Like Father, Like Son”, it could be argued that crime and poverty are actually not the thing he was most concerned with. He cares more about family bonds and has said that he wanted to explore how these bonds work, if the family is not related by blood but by crime. So his focus was likely not on the crime and poverty and its questions of morals or ethics. He also seems to have taken care not to judge them too much. Given the past works of the director, it is probably not a surprise that “Shoplifters” is not a sadder movie because he is skilled at treating family drama with subtlety.

Nevertheless, the question of right or wrong, good and evil still arises in the mind of the audience. When deciding to write a story about shoplifting, it would be naive to ignore that. As this essay has shown, Kore-eda does in fact deal with the subject in a subtle way. He does it quietly and gently, without judging directly. This indicates that he trust that the audience is capable of reflecting on these heavy subjects and form their own opinion about the legitimacy of the family bonds and their ethics. He does not dictate meaning with unnecessary drama.

It could even be argued that wrapping these difficult questions in a happy blanket makes them easier to deal with. After watching similar heavy subject movies like “Terrorizers” by Edward Yang or “Parasite” by Bong Joon-ho, audience members might struggle more with stomaching the violence and sadness they just witnessed. It takes a strong gut to still want to evaluate a heavy film and its implications afterwards. Especially nowadays, when a large part of movie going is motivated by escapism, movies of “Shoplifters”‘ subtlety are arguably more successful in reaching the audience than more heavy-handed dramas.

We can count ourselves lucky that Koreeda made a film that whispers when many others are shouting. “Shoplifters” is not sad because this filmmaker probably understands that nuance and grey areas are what make his movies accessible. It should not be sadder because he gives us the chance to genuinely enjoy the heart-warming energy of his work, while still allowing us the intellectual challenge of judging the characters for ourselves.

It takes a master of subtle storytelling to give us an uplifting story that stands true to the difficult world we live in. With our modern family structures ever-changing and challenging us, “Shoplifters” stands as an immensely valuable resource for enjoyment but also reflection.