by Earl Jackson

In 1969, Masahiro Shinoda released “Double Suicide”, his version of Chikamatsu Monzaemon's bunraku (puppet) play, “The Love Suicides Amajima” [心中天網島]. The film was striking in its use of the black-hooded puppeteers, the kuroko, to move the actors and change the deliberately artificial sets. The film was a hit with the international art film crowd in that it proved that Japanese avant-garde narrative cinema was not limited to Hiroshi Teshigahara's adaptations of Kobo Abe novels. In later years, it would serve as a viewer-friendly introduction to the New Wave because, unlike the more difficult works of Kiju Yoshida or Nagisa Oshima, “Double Suicide” -to repurpose Gertrude Stein's judgment of James Joyce – was the experimental film that anyone could understand.

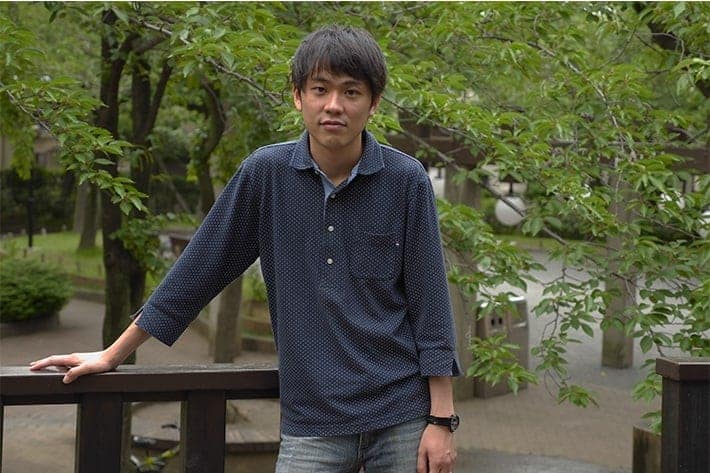

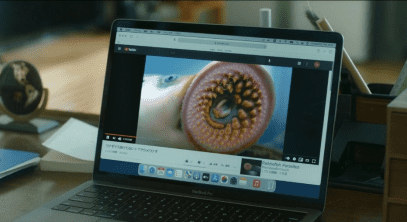

In 2021, Ryusuke Hamaguchi takes up the challenge of integrating classical theater with contemporary cinema again, in his use of Chekov's “Uncle Vanya” in his film “Drive My Car”. At first glance, Hamaguchi's inclusion of scenes from the play may seem more conventional than Shinoda's film, but what distinguishes the former is not its radicality but its intimacy. “Drive My Car”, in fact, obviates the question of convention and innovation because, like Hamaguchi's previous works, the movie constitutes an act of concentration so committed to its process that even the distractions it admits become oracular, whether or not the oracle divulges its message- as we have seen in the communication workshop in “Happy Hour” (2015), Torii Baku's (Masahiro Higashide) late reappearance in “Asako I and II” [寝ても覚めても] (2018) or in the scene in “Drive My Car” when Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) closes his laptop on the video close-up of a lamprey's ravenous maw (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The lamprey as oracle. “Drive My Car” (Ryusuke Hamaguchi, 2021)

In thinking through Hamaguchi's “Uncle Vanya”, I first recalled earlier films that quoted stage performances of one form or another. I would like to approach an initial appreciation of “Drive My Car” with a selective survey of these films. In terms of Japanese cinema history, it seems fitting to begin with the two earlier films that also reference Chekov.

“Warm Current” [暖流] (Kozaburo Yoshimura, 1939) excised all references to the war in China from Kunio Kishida's novel to create a gauzy upper-class melodrama about two women in love with the same forensic accountant (Shin Saburi). One of the women, Keiko Shima (Mieko Takamine) was the daughter of the doctor who owned Shima hospital, where the notorious cad, Dr. Sasajima (Shin Tokudaiji) worked and preyed on the nurses. For the sake of his future, Sasajima set his sights on marrying Keiko, and to that end, he takes her to a nature reserve in Kamakura to make his case (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The proposal in a dream park. “Warm Current” (Kozaburo Yoshimura, 1939)

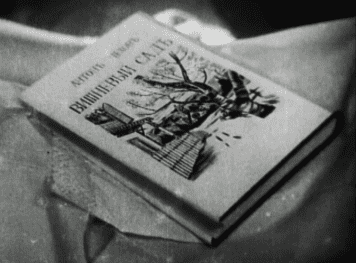

Keiko, however, not only seems unmoved by his ardor, she even brings along a book: Chekhov's “The Cherry Orchard” in the original Russian (Fig. 3)! This serves not only to indicate her intellectual prowess but the play's story of a wealthy family that falls into ruin foretells the fate of the Shima family.

Fig. 3. Bringing Chekhov's Вишнёвый сад on a date. Warm Current (Kozaburo Yoshimura, 1939)

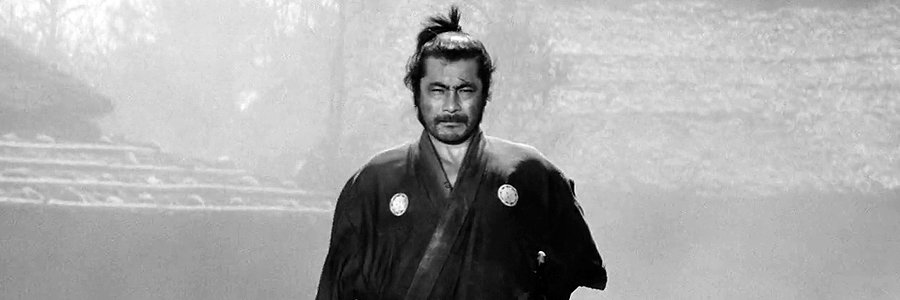

Twenty-one years later, Chekhov is again evoked to recontextualize contemporary suffering in “The Skin of the Evening” [赤坂の姉妹より夜の肌] (Yuzo Kawashima, 1960). The film follows the obstacles and upheavals in the lives of the Natsumi sisters. The two elder sisters, Natsuo (Chikage Awajima), and Akie (Michiyo Aratama) had been working as hostesses in upscale Akasaka restaurants for several years when the youngest sister, Fuyuko (Tomoko Kawaguchi) arrives in Tokyo from their hometown to attend university, where she soon joins a group of student activists. In nearly the penultimate scene, Natsuo and Fuyuko attend a performance of Chekov's “Three Sisters”, and the film focuses on their faces during the climax of the drama, where the three Porozov sisters, shattered but undefeated by a series of catastrophes, vow to keep on working, to keep on living (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The Prorozov Sisters on a Tokyo stage. “The Skin of the Evening” (Yuzo Kawashima, 1960).

This scene instantly reinterprets the entire film, as it clearly demonstrates the parallel between each individual sister: Olga, the eldest sister, begins as a teacher and is promoted to headmistress. Natsuo begins as a hostess in the bar, Shiinomi, and through hard work and terrible sacrifices succeeds in owning the restaurant, Magokoro (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Natsuo watching Olga. “The Skin of the Evening” (Yuzo Kawashima, 1960).

Masha, the middle sister, like Akie, is bitter, short-tempered, and endures an unhappy relationship. Irina is the youngest and most idealistic of the sisters, which is also true of Fuyuko (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Fuyuko moved to tears by Irina's convictions. “The Skin of the Evening” (Yuzo Kawashima, 1960).

On stage, the three sisters embrace and persevere together in spite of the tragedies that have befallen them, a scene that must be particularly painful for Natsuo since the events she and her sisters have endured have driven them farther apart and vanquished her dream of them working together in Magokoro. Beyond the simple parallels between the two sets of sisters, the scene achieves an encounter between “High Culture” and popular culture on an equal footing. The surprise appearance of “Three Sisters” does not elevate the melodrama but illuminates what the genre was already capable of achieving in representing the lives of women in a patriarchal social order.

In looking at these precedents, I am not suggesting that Hamaguchi drew from them. Beginning in the Meiji period (1868-1912), Russian literature was widely translated and read. Shimei Futabatei (1864-1909), credited with writing the first modern Japanese novel, was an avid lover of Russian literature. He not only translated Tolstoi and Turgenev, but studied in Russia and even wrote a travel diary in Russian. The novelist Yutaka Haniya (1909-1997) published over 2,000 pages of essays on Dostoevski. When in an especially good mood, my religious studies professor in graduate school, Masatoshi Nagatomi (1926-2000) would sing an aria from the Japanese opera adaptation of Tolstoi's novel, “Resurrection” [Воскресение], which he and all his classmates were taught in middle school. Hamaguchi, therefore, is operating within a very long, and variously rooted tradition in his work with Chekov.

[Part Two will examine Hamaguchi's orchestration of the voice, “Uncle Vanya”, and techniques drawn from Noh.]