Considered by many as Susumu Hani's best work, co-produced by Art Theatre Guild and co-written by Shuji Terayama “Nanami: The Inferno of First Love” is a movie that highlights the artistic freedom filmmakers of the Guild had in the 60s, in a title that would very difficult pass from any kind of censorship committee nowadays. Despite its occasionally offensive premises, the movie screened in the US with a 20 minutes cut, grossed over $1 million in Japan and competed for the Golden Bear award at the 18th Berlin International Film Festival in 1968.

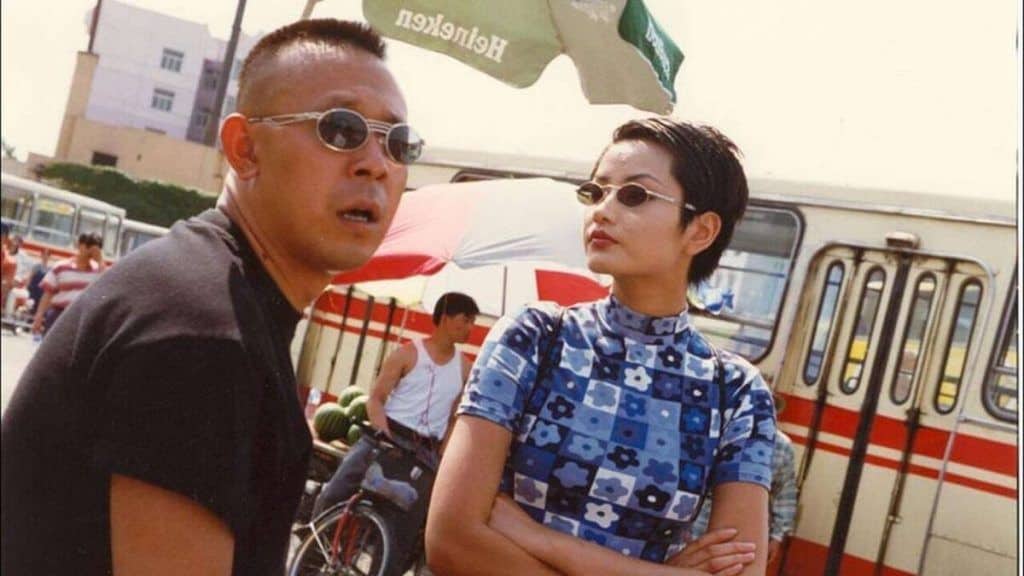

The story revolves around Shun, a virgin 17-year-old who works as a goldsmith in his stepfather's workshop, and Nanami, a young nude dancer. As the film begins, the two meet in the club she works at and immediately fall in love with each other, ending up in a love hotel. Shun is unable to have sex with her, but she is understanding, and the two open up about their past that led them to the lives they have now. In flashbacks, it is revealed that Shun was and is still sexually abused by his stepfather, that his mother abandoned him for a man when he was little, and that he retains a relationship with a little girl h e considers his girlfriend that could easilybe described as pedophilia. Nanami, on the other hand, came from Shizuoka to Tokyo and started working as a dancer because her former job didn't pay enough. As the duo get more and more into Tokyo underworld, particularly after Nanami and a number of her colleagues are convinced bu Ankokuji, one of her customer,s into participating into an erotic, sapphic-like photoshoot where they either pretend to fight or make love dressed in costumes. As yakuza and other members of the red light district get increasingly involved, thus the danger to the couple also grows.

Through a cinematic style that can easily be described as delirious, both in terms of Yuji Okumura's occasionally absurdly angled frames and Hani's own frantic editing, the director manages to make a number of rather pointed comments, most of which seems to criticize anything that was considered the norm at the time, including all kinds of political correctness, and in general, anything that was (and still is) perceived as sacred.

The first that becomes evident is the concept of family in its many facets. The mother who abandons her child to follow her lover, the stepfather who molests his son, even Shun's relationship with the little girl, which borders somewhere between that of a parent and a child, and two lovers, all move towards the same direction, completely deconstructing the concept. At the same time, Hani seems to state that sex is the most powerful driving force in the lives of people, since, essentially all events that take place in the story, derive from that. This element also extends to the photograph sessions, Nanami's relationship with her customers, even to Shun's eventual jealousy, with all three also highlighting the connection between sex and money in a way that is realistic (pragmatistic if you prefer) but also cruel. This comment, in combination with the attitude of the “public” when Shun's endeavors with the little girl come to the fore, also highlights the hypocrisy that dominates society, particularly regarding the concept of sex and lust, and how much control people have on them. The same applies to the scene when the couple visits a school to watch a movie one of Nami's friend's has shot, where the self-perceived liberal students are quite judgemental of her appearance, gossiping about her in a way that exhibits both jealousy and racism.

A special place in the overall mockery that characterizes the narrative is held for psychology, with the sessions Shun undertook as both a child and an adult bordering on the ridiculous, in an approach that is both funny and rather pointed.

The fact that all individuals appearing in the story are utterly conscious and unapologetic regarding their actions (including the little girl) can be perceived as a comment on human nature but is also a rather original narrative element, since the usual approach, at least in the case of Shun's deeds, includes some kind of remorse.

At the same time, the movie also follows the path of a tragic romance between two rather faulted individuals, whose love and relationship has to face the cruelty of the world, as much as their past that has shaped them as characters.

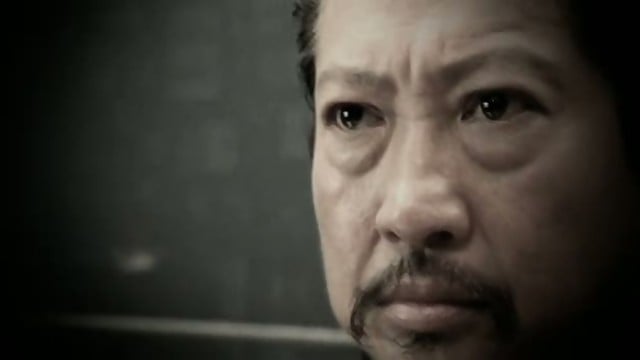

The same originality characterizes the production values, with the documentary-like approach in both editing and cinematography frequently resulting in a cornucopia of elements including a plethora of still photos, music-video like sequences, abrupt cuts, intense close-ups to the face of the protagonist that focus on their teeth, and much nudity. The result is an audiovisual feast that is at least as rich as the context. Also of note is the way Okumura has shot the scenes between Shun and the girl, which are mostly implied, but still end up being quite disturbing.

Kuniko Ishii as Nanami gives a delightful performance, essentially being constantly cheerful even in the more intense moments, while her evident beauty is one of the main elements of the visual approach here. Akio Takahashi as Shun has a more difficult role, presenting a man that initially appears as a victim but is soon revealed as something much worse, and is quite convincing in it.

“Nanami: The Inferno of Love” is a truly great movie, a title that highlights both the artistic freedom of the ATG productions and Susumu Hani's directorial abilities in the best way.