The movies produced by the Art Theatre Guild form one of the most interesting part of Japanese movie history, particularly because the filmmakers involved enjoyed unprecedented creative and artistic freedom, which resulted in a series of truly unique films. This is the main reason that we decided to deal with the particular titles for our February and March tribute, one that will definitely continue until we manage to have articles for all. Until then, however, and in a tactic we will continue with the rest of our tributes, we decided to also publish a synopsizing list of the movies we already wrote about, one that will expand as more articles come in. Here is what we have as of now, in chronological order.

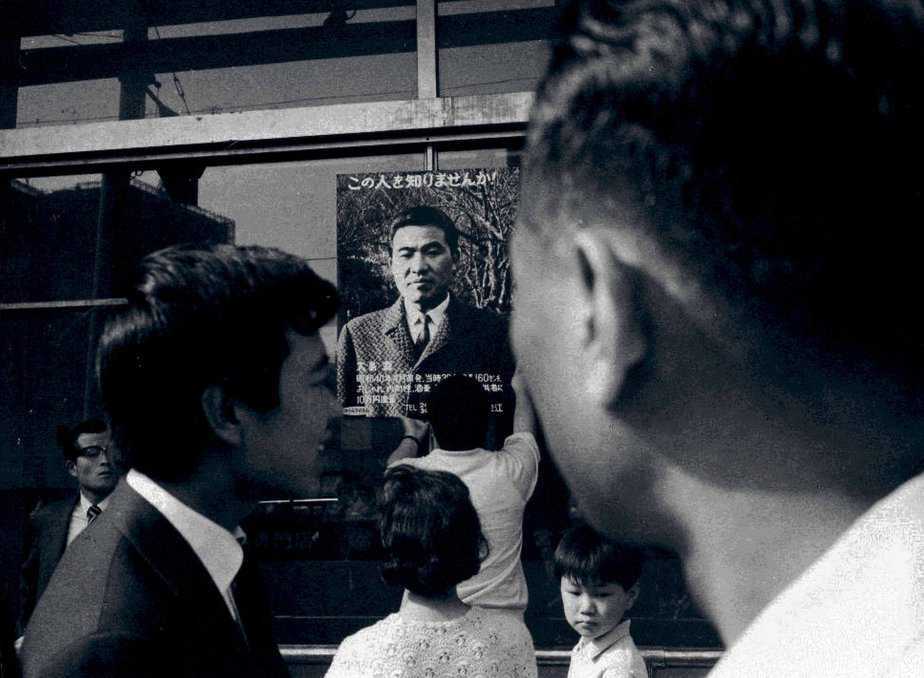

1. A Man Vanishes (1967) by Shohei Imamura

Right from the beginning, we get an impression of an utterly chaotic experiment, while, as the story unfolds, we can figure out that the core of the film is carefully being constructed with an amazing, almost surgical precision. An essay, which at first glance seems destined to drive us straight to nowhere. However, it fully succeeds on working under the surface, in a really fascinating way. To be more precise, the thing is that while w are heading towards this dead end, in the meantime, Imamura and his crew, dominated by an almost fetishistic fixation, seem like they want to peel off numerous layers of a modernized society against old fashioned customs, in a parallel with the foundations of human bonds, while they also perform an examination of the inner psychology behind these factors. The camera is used almost like a scalpel, as we watch them perform a number of ‘dissections' onto an unknown body and in cold blood. Nevertheless, it manages to remain focused on certain targeted objects. Yes, this is one of these creations which resembles an in-depth introspection regarding its object of examination, an artistic equivalent of an anatomy class for those who are familiar. (Nicholas Poly)

2. Human Bullet (1968) by Kihachi Okamoto

As Him continues to move in the area, a truly dystopian setting is revealed, excellently photographed by Hiroshi Murai, while the road-movie style takes over completely, in Okamoto's effort to criticize/satirize as many concepts as possible. Probably one of the most pointed ones comes upon the appearance of the teacher and his two students, one boy and one girl, which shows how similar the rhetoric and the practices of the school and the army were at the time. The appearance of the three women, and their references to Greek philosophers and Sada Abe is probably the most hilarious moment in the movie, while their eventual fate also highlights how the war turns people to animals. Lastly, the eventual fate of his “Human Bullet” mission, once more showcases the ridiculousness of the whole concept, including the kamikaze one. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

3. Nanami: The Inferno of First Love (1968) by Susumu Hani

The first that becomes evident is the concept of family in its many facets. The mother who abandons her child to follow her lover, the stepfather who molests his son, even Shun's relationship with the little girl, which borders somewhere between that of a parent and a child, and two lovers, all move towards the same direction, completely deconstructing the concept. At the same time, Hani seems to state that sex is the most powerful driving force in the lives of people, since, essentially all events that take place in the story, derive from that. This element also extends to the photograph sessions, Nanami's relationship with her customers, even to Shun's eventual jealousy, with all three also highlighting the connection between sex and money in a way that is realistic (pragmatistic if you prefer) but also cruel. This comment, in combination with the attitude of the “public” when Shun's endeavors with the little girl come to the fore, also highlights the hypocrisy that dominates society, particularly regarding the concept of sex and lust, and how much control people have on them. The same applies to the scene when the couple visits a school to watch a movie one of Nami's friend's has shot, where the self-perceived liberal students are quite judgmental of her appearance, gossiping about her in a way that exhibits both jealousy and racism. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

4. Death by Hanging (1968) by Nagisa Oshima

Oshima presents a rather harsh critique towards the authorities, whose people are depicted as caricatures, while he considers their obsession with crime more intense than any criminal's. This mentality, according to him, is what transforms misguided wrongdoers to genuine criminals. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Double Suicide (1969) by Masahiro Shinoda

Shinoda's exploration of free will, love, lust and death is a tragic tale, a sad downward spiral towards an inevitable conclusion where false hope occasionally pops up only to be knocked down immediately by a cruel twist of fate. “Double Suicide” mercilessly builds up towards the tragic titular shinju while the characters struggle in vain to avert the grim end the universe has written out for them. It's a fantastic retelling of the old story and displays Shinoda's ability to balance avant-garde impulses with more traditional storytelling. Captivating, sorrowful and surely even more rewarding upon multiple viewings.

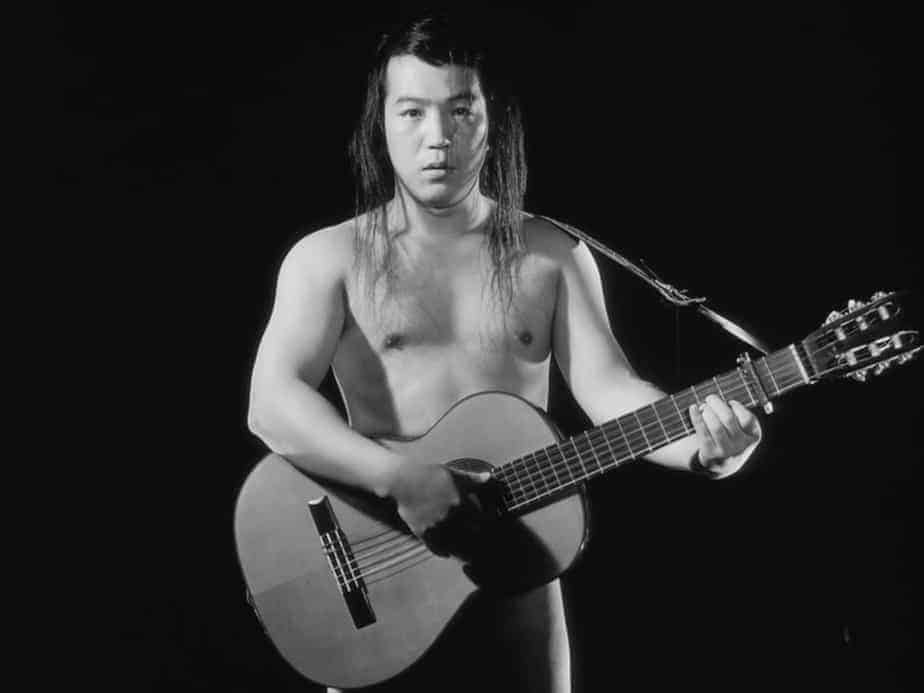

5. Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969) by Nagisa Oshima

Considering the overall context of upheaval and sexual freedom, acts such as stealing may constitute steps in becoming free of whatever social chains one feels around him or her. In the opening scene we see a thief, who is later revealed as a member of a performance group, caught by several men on the streets of Tokyo. Following their demands of returning the stolen goods, he is forced to strip, an act of degradation and humiliation since people around him are watching everything. Finally, wearing nothing more than his underwear he becomes superior over the other men as he has rid himself of inhibitions and sense of moral. Birdey's and also Umetsu's dilemma is then how to take the next step, how to unwind the remains of their social identity and to be free, to lead a more wholesome existence maybe. (Rouven Linnarz)

6. Funeral Parade of Roses (1969) by Toshio Matsumoto

Matsumoto often mixes different tones in one scene. Most of the time he achieves this through the non-diegetic music he uses. He constantly uses a motif that is reminiscent of the melody and texture of a music box sound, to go with events that other directors would treat with greater seriousness. In a scene where two men are putting on clothes to avoid a police's raid, the director accompanies this scenario with the music box sound. Furthermore, he fast forwards their actions; thus makes them look even more ridiculous. These minor techniques transform an intense situation into a farcical one. The most striking one comes at the end of the film. I don't want to ruin your viewing pleasure. It's safe to say that it is the best “alienation effect” I've seen in film or TV. (I Lin-liu)

7. Apart from Life (1970) by Kei Kumai

Kei Kumai directs a multileveled film, whose main goal seems to be to highlight the consequences of atomic bombing in a sociophilosophical and psychological context, in a setting that is inhabited just by outcasts. Regarding this last aspect, his characters include people who are essentially ousted from their own harbor that has been taken over by US forces, while the rest of them are either Catholics or Koreans or burakumin or radiation poisoning victims, essentially minorities in the country. What emerges as the most shocking element however, is that the last ones are at the bottom of the “caste system” even lower than the burakumin, a concept that essentially brings us to the main goal purpose here, of showcasing the consequences of the A-bomb. That this is one of the very rare (if any) chances that films about Hiroshima refer to this aspect, is where the biggest value of the movie lies. At the same time, the discrimination against the discriminated element presents another comment about human nature.

8. Heroic Purgatory (1970) by Kiju Yoshida

In the end, this level of confusion as explained above is a natural reflection of the emotional state of the characters. Whereas the young girl Nanako has picked up seems scared and “lost”, as we are frequently told throughout the movie, the central couple is also dysfunctional in the sense they seem to have forgotten how to behave like a couple, only functioning properly when alone. Mariko Okada and Kaizo Kamoda give great performances as people whose experience with the past (or rather encounter) has a rippling effect on their present, creating a feeling of discomfort when compared to their former self. Considering the historical context of 1970, Yoshida confronts his characters, and also the viewer, with the ideals of the student movement of the past decade, questioning what will remain of their goals and aims once everything has returned to normal. The recurring images of monitors, of people being observed and the loud ticking of a clock may just be the most foreboding sequence of “Heroic Purgatory”, and a deeply pessimistic prediction of what may come in the next few years. (Rouven Linnarz)

Evil Spirits of Japan (1970) by Kazuo Kuroki

On the surface, “Evil Spirits of Japan” reads just like many yakuza movies of the time. However, similar to his contemporary Seijun Suzuki, Kazuo Kuroki attempts to undermine the genre conventions, using them as a mere platform to discuss and present observations on Japanese society. Kei Sato plays the two main characters seemingly identical, making it difficult to tell them apart if it wasn't for the different clothing. Their playful encounter at the beginning is one of many anti-climatic moments which is highlighted by Sato's understated performance, further stressing the idea of cop and gangster being interchangeable. While this approach has its downfalls, the creative ways Kuroki employs to make this story entertaining and often quite relevant result in some memorable scenes. (Rouven Linnarz)

9. This Transient Life (1970) by Akio Jissoji

Incest was one of the recurring themes of ATG films during the 60s and early 70's, in productions like Toshio Matsumoto's “Funeral Parade of Roses” or Kazuo Kuroki's “Preparations for the Festival”. However, Akio Jissoji's presentation of a theme that still remains taboo is probably the most scandalous, particularly because his characters do not seem to have any remorse about their deeds at all, while Masao barely hides the fact, even clashing with the people who learn the truth, at least the ones who manage to confront him. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

10. Mandala (1971) by Akio Jissoji

From the beginning, it is obvious that Jissoji wants to implement a sense of disorientation, placing his viewer into a state that will allow him to experience the film not with his logic, but neither with his senses exactly (especially not his vision) but through a completely clean sheet, as the occurrences on the screen seem to go against both the aforementioned methods of understanding a work of art. His method however, apart from the, once more, impressive and unique visual tactics of Yuzo Inagaki's cinematography, is quite extreme, particularly since the repeated rapes on screen seem to be one of the main mediums of this effort. This aspect can be perceived as an effort to include pinku elements in the film, as was the case with the whole trilogy, but remains quite difficult to watch, even in exploitation terms. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

11. Demons (1971) by Toshio Matsumoto

“Demons” is a bleak and nihilistic affair, a pitch-black take on samurai films and Shakespearean tragedy, set in a hellish world of dark, ominous shadows and demented bloodlust. The narrative is a slow descent into complete and utter madness, a descent that's hinted at in the first shot of a setting sun, the menacing red sky being the only instance of color in the film's 134-minute runtime. Often billed as a horror movie, it might more accurately be described as a slow and surreal psychological horror drama, as much about its main character's dissolving sense of reality as it is an indignation of the ugly world the supposedly heroic samurai helped create, the pools of blood and severed limbs painting a picture of a society in complete disarray. (Fred Barrett)