12. Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (1971) by Shuji Terayama

Terayama makes us watch as the protagonist stumbles from one tragedy into another, desperately searching for some kind of subjectivity. His father is the local pervert who sexually harasses young girls and has no money, his sister is trapped in a quasi-bestial relationship with her pet rabbit and his grandmother is a lying shoplifter who thinks of nobody but herself. The film employs recurring acts of violation in order to facilitate the genesis of an atmospheric anxiety which does not go away even after it ends. The protagonist dreams of becoming a “human aeroplane” and flying away from his suffocating life to the hypocritical promises of America. However, he flails around in his own Freudian nightmares and witnesses the slow unravelling of his family. (Swapnil Dhruv Bose)

The Ceremony (1971) by Nagisa Oshima

Oshima uses the story of the family as a metaphor for Japan, in a critique that only grows harshest as more of the past is revealed, focusing on how the individual is essentially completely disregarded for the sake of family and lineage, but also extending on a number of other issues. In that fashion, the issues Masuo and his mother face as soon as they return, with him expected by Kazuomi, his grandfather and undisputed leader of the family, to live for both himself and his deceased brother, essentially baring double the burden on him, and his mother facing suspicions of having become a ‘relief woman' during the war. Furthermore, Masuo finds himself repeatedly having to sacrifice his dreams and wishes for the ‘good of the family', with the grandfather fully controlling his and all the family members' lives, including their erotic relationships and their marriages.

13. Poem (1972) by Akio Jissoji

Even though the idea of change is omnipresent within the film, there is a distinct skepticism towards the nature of it, especially as it is forced by the characters. An early sequence showing Yasushi and his wife together with his parents may hint at the huge gap between two generations. Keeichi Uraoka's editing highlights this emotional and ideological distance as well as the architecture of the shot, for example, by showing Yasushi in a close-up or him turning away from his father smoking. His business suit seems to be the perfect uniform, a significant difference to the kimono his father wears. In contrast to his servant Jun, his visits to his parents have a distinct utilitarian motive, whereas Jun associates these visits with his beliefs and traditions, such as the Bon Festival and other important festivities. Given the nature of the representatives of change in the film, it seems more selfish and destructive, devoid of any positive aspects. (Rouven Linnarz)

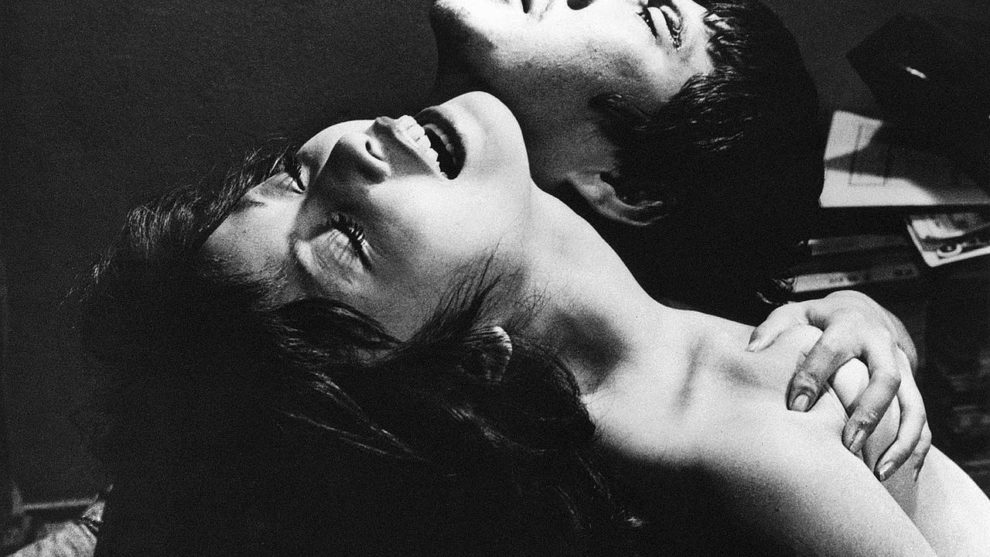

14. Ecstasy of the Angels (1972) by Koji Wakamatsu

The style of “Ecstasy of the Angels” shares many similarities with “Sex Jack” particularly through the narrative form that follows a succession of violence, sex, and political discussion, which occasionally happen at the same time on screen. The differences, however, are quite significant also, as the bigger budget allowed Wakamatsu to include the noir scene previously mentioned, which also happens once more close to the end of the film in a triumph of style, coolness and minimalism, and a number of exterior action scenes. These are quite impressively directed, with Wakamatsu implementing a rather chaotic approach, which ends up, though, seeming realistic, in a testament to his abilities, with the same applying to both Hideo Ito's cinematography and Hajime Tanaka's editing. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

The Morning Schedule (1972) by Susumu Hani

Describing “The Morning Schedule” is quite a difficult endeavor, considering how unusual and complicated the narrative is. The film-about-film concept is probably the most prevalent, with the two watching a number of Kusako's movies, and reminiscing about their youth together, as much as learning a bit more about her inner thoughts. Each of the three major actors was allowed to shoot part of the movie, which is shot partially on 35mm black-and-white and partially at color 8mm, adding the aforementioned found footage aspect, while intensifying the meta component here. The films Kusako has shot also differ significantly, with some of them focusing on a brief relationship she had with a man, other focusing on Tsuji and Reiko, and others simply on herself. Lastly, another arc deals with the teacher of three, and how he also tries to make sense of the suicide while trying to communicate a rationalization to his students in the classroom, most of which, however, do not seem to care particularly, in an aspect that can be perceived as a comment regarding the mentality of both students and teachers.

15. Hymn (1972) by Kaneto Shindo

Kaneto Shindo directs a film about love and the ways it can function in the darkest fashion, if the people involved complete each other. The relationship of Shunkin and Sasuke is sadomasochistic from the beginning. She seemingly enjoys bullying him in the harshest way, fully exploiting his adoration for her, and he accepts her behaviour as the highest honor, literally worshiping the ground she steps on, to the point that even the chore of burying her excrements in the garden is an honorable ritual for him. As the years pass by and he keeps staying by her, her dependence on him becomes more intense, to the point that she wants no one else but Sasuke close. The inevitable erotic implications add to the whole S&M setting, although their result is quite shocking and highlights how their codependence has made them not wishing for anyone who even dreams of disrupting it beside them.

Tsugaru Folk Song (1973) by Koichi Saito

Koichi Saito directs a truly bleak story, a kind of social melodrama, as he presents a number of characters, who, for a number of reasons, are stranded in a place they want to abandon but fail to do so. The reasons each one has actually form one of the most interesting aspects of the movie, and are also the main source of the plethora of sociopolitical comments that appear throughout the movie. Isako is essentially there due to her love for Tetsuo, which is the reason that when she feels it is over, she starts feeling the need to leave once more. At the same time, the bonds of grief for the loss of her father and brother are still evident, as much as her wish to get the insurance money. That she fails to get it makes a comment about how the system works, with the fact that she is later essentially forced to work as a hostess to earn some money, both adding to the remark and highlighting another bond that does not let her leave. That love and lack of money essentially have the same result is a rather pessimistic comment here, which is actually how the whole film works.

Aesthetics of a Bullet (1973) by Sadao Nakajima

1973 proved a big year for the deconstruction of the yakuza on cinema, with Kinji Fukasaku releasing the first three parts of the Yakuza Papers, with the reality of “the life” finding its way into cinema in the most “in-your-face” fashion. Nakajima was definitely part of this ”trend”, with “Aesthetics of a Bullet”, however, being at least as much a character study and a critique of the way capitalism functioned in Japan at the time. To begin with the first aspect, Nakajima introduces us to a true loser, a man who just functions with his instincts without being able to think even for a moment, thus becoming fodder for powers higher than him, and particularly the Yakuza, highlighting in that way, how these criminal organizations handled their recruiting. Kiyoshi has a couple of “saving” qualities, seems to be quite a strong fighter and also to have an appeal on women, but none of these two can actually save him, as the two main females he meets in the story are eventually turned away by his ways, and his power actually brings him into more trouble. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Battle Cry (1974) by Kihachi Okamoto

Okamoto's ironic and parodying sense of humor is found all over the movie, but the main root of that element is definitely the repeated montage of warriors battling and Sentaro and Manjiro having sex, in a rather mocking element that is bound to make any viewer laugh with its obviousness. Furthermore, the fact that the two poor devils are having sex while the ‘noble samurai' get themselves tortured, disgraced and killed definitely moves in the same fashion, as does the fact that the two, who are considered by the warriors as lowly peasants, are actually the one who manage to be truly happy.

Himiko (1974) by Masahiro Shinoda

Evidently, Masahiro Shinoda creates a labyrinthic story that shows the rather intricate relationships of the protagonists, in a style that can easily be described as Shakespearean, considering also the fate most of the key characters face in the end. The symbolism and the metaphors are essentially all over the story, and discerning them all would fill a number of pages. Some of the most evident, though, concern the relationship between state, religion and people, with Shinoda eventually showing the latter, or at least the ones considered the lowest, as the “winners” at least in individual terms.

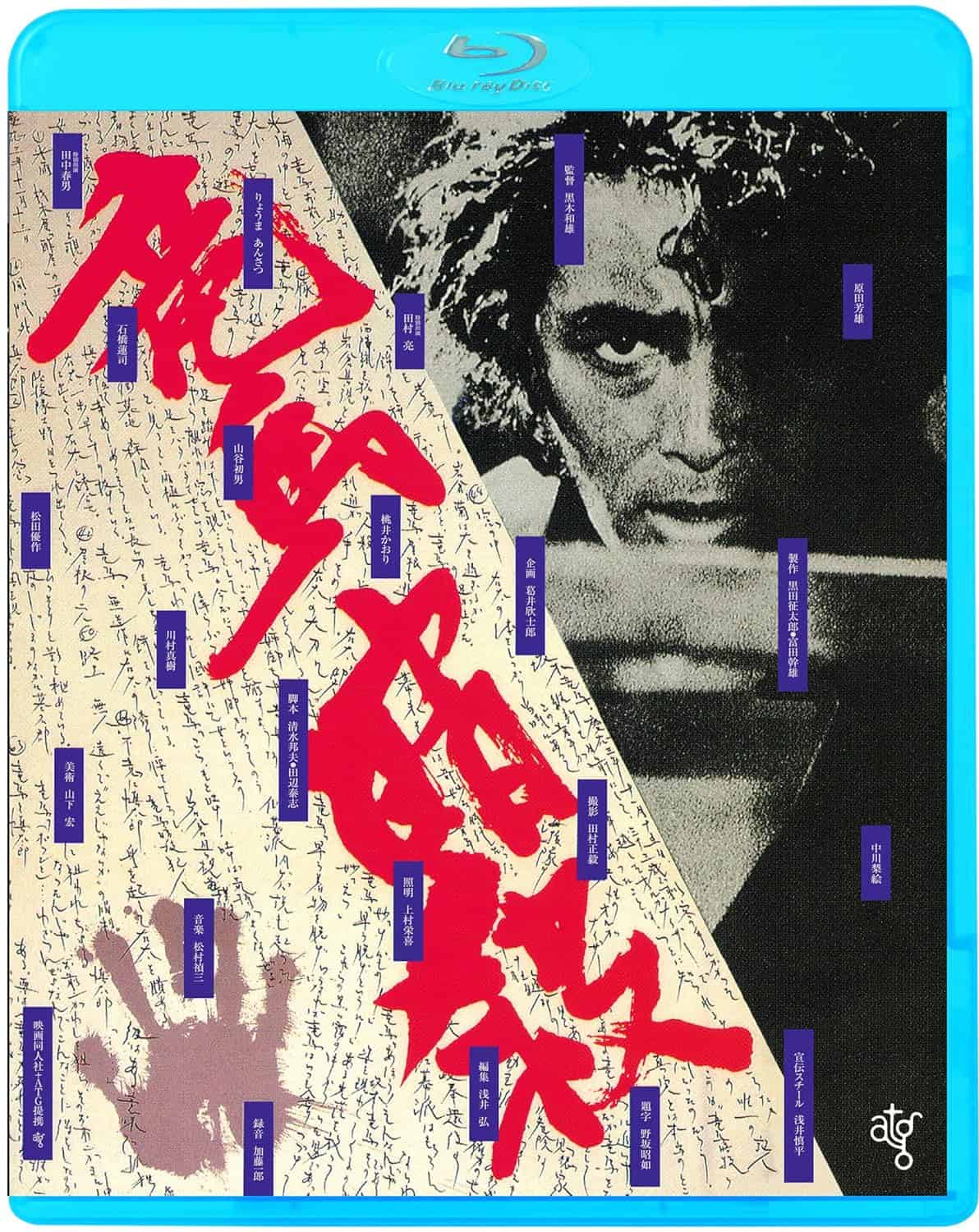

The Assassination of Ryoma (1974) by Kazuo Kuroki

While he could easily shoot an epic about a truly significant persona of the Japanese history, Kuroki instead chose to shoot a fable that not only deconstructs, but essentially mocks the whole concept of the samurai, by presenting the majority of them as confused, sex-crazed, poor and irrelevant buffoons, who seem to be driven only by a misguided sense of duty to something they do not even know what it is. As such, the movie is filled with humoristic episodes and much sex, while the various action scenes seem to take place in a space and time that does not concern the protagonists in particular.

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

16. It Was a Faint Dream (1974) by Akio Jissoji

Similar to his previous film “Poem”, Akio Jissoji presents an intimate drama as a mirror to profound changes within the society as portrayed in the movie. Although the viewers see brief scenes showing the severe poverty and misery on the streets, the world of the court seems untouched by any of these circumstances. Much like the mansion in “Poem”, the affairs of the men in charge are discussed behind closed doors, remain power struggles slowly corroding the sense of unity among their own.

Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974) by Shuji Terayama

The concept of the film-about-film is somewhat complicated by itself in its presentation, but it is just one part of a narrative here that can only be described as labyrinthical. As the past and the present melt onto one another, so does the border between fantasy and reality, with Terayama actually making a comment about memory and particularly that of children, which does not always match reality. Furthermore, all the aforementioned story parts we mentioned are actually only a portion of what is happening, with Terayama also including a dystopian element that takes place mostly in the scary mountain, while dancing, eroticism, love and its exploitation, and the concepts of time and sex also come to the fore. The voyeurism that Shin-chan exhibits repeatedly could be perceived as one of the elements of becoming a director, while the questions the adult Shin has about his art are also an integral part of the whole concept regarding what it is to be a filmmaker.

Song of the Devil (1975) by Tetsutaro Murano

Tetsutaro Murano directs a film that is essentially about obsession, highlighting how, particularly in art, it can lead to greatness, but also demands intense levels of self-sacrifice. The concept is ambiguous in theory, as it poses the question of if it is worth it, practically putting excellence in art and self-preservation (also including the people who are close on occasion) in complete contrast. Bakyo's story mirrors the concept in the most eloquent fashion, as we watch him coming up with increasingly more extreme ways to succeed, essentially neglecting both his wife and himself. The fact that both these eventually become part of his performance is another comment that moves in the same direction. At the same time, and as stated in the introductory scene, where a series of still photos show a rakugo artist being interviewed, Murano states that art could reach different heights, when artists were poor and obsessed, instead of rich and pampered as they are occasionally today.

Preparation for the Festival (1975) by Kazuo Kuroki

Evidently, there is an abundance of episodes and characters here, all of which however, aim at highlighting the dead-end all of them find themselves in, particularly due to the way life unfolds in small communities, and the desperate ways they find in order to cope. In that fashion, Takeo wants to leave in search of a better future but also in search of sex. His father, who could not leave, channeled his frustration towards relationships with women, while his mother, not having any alternative, has latched herself onto her son, essentially imprisoning him with her behavior.

Youth Killer (1975) by Kazuhiko Hasegawa

Kazuhiko Hasegawa directs a film that channels the frustration and the anti-establishment feelings of the era in Japan in the most brutal fashion, essentially presenting a young man that everyone around him try to dictate how he will live, eventually leading him, inevitably one could say, to violence. That both his parents are erratic, with his father hiring a detective to check on Keiko and his mother presenting herself as a paranoid sociopath, who seems to somehow have been prepared for the murder of her husband, highlights the aforementioned, quite eloquently. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Death at an Old Mansion (1975) by Yoichi Takabayashi

Drawing from Sherlock Holmes novels, Yoichi Takabayashi presents a locked room mystery, which is, however, quite innovative cinematically and manages to make a number of sociopolitical comments through its whodunnit approach. Regarding the latter, the concept of the whole “caste” system is immediately highlighted from the wedding scene, actually encompassing the whole narrative, with Rinkichi Kubo and his daughter Katsuko being looked down because the former made his money due to successful entrepreneurship and not by legacy as the Ichayanagis The protests of the latter family regarding the wedding stresses the fact even more, as it becomes clearer as the movie progresses. The concept, which is essentially racism, is also extended to the three finger stranger, who, due to his unknown origins and his scarred face, is immediately perceived as the villain and the prime suspect for the murder, with the three fingers of the two bodies, essentially considered proof of his guilt. Lastly, the place of women in society is also highlighted throughout, with the fact that it is the men that ruled the world being eloquently showcased throughout the movie, eventually becoming part of crime.

Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? An Encounter (1975) by Kenji Yoshida

Evidently, the way Katsuo pursues Kumi and the fact that he actually succeeds in his stalking/courting is something that would offend many, both in its presentation and the message it sends. Considering however, the era the film was shot, which was actually quite prevalent in ATG films, the whole arc is to be expected. Apart from the slightly exploitation approach here, Kenji Yoshida uses the dead-end relationship of the two for two purposes: to analyze his characters and the way they are shaped through it, and to make a number of sociopolitical comments.

Sea of Genkai (1976) by Juro Kara

Despite the fact that the movie begins as a comedy (the “Hail McArthur” moment will definitely stay on mind) which mostly mocks the yakuza ways by presenting all of them and particularly Sawaki as caricatures, quite soon it turns into a drama filled with exploitation elements, before it concludes as a melodrama, retaining though, its grotesque premises. As such, the focus soon changes from the aforementioned mocking to highlight the torturing Koreans suffered in the hands of the Japanese, with the concept starting with stealing, raping and killing in 1951, and essentially continuing in the same fashion even during the 70s where the story seems to be taking place in.

Variation (1976) by Ko Nakahira

The European art-house aesthetics are prevalent in the movie, with a very thin story that seems to aim at making some comments regarding what happened to the revolutionaries of the 60s, while presenting the continent from the perspective of the Asians. At the same time, the many erotic scenes give a hint that Nakahira may have been inspired by “Emmanuelle”, with the protagonist also looking somewhat like Sylvia Kristel on occasion. This does not mean that “Variation” is as titillating as the French movie, but the pinku elements are definitely here, and done in much more tasteful fashion than in the Japanese productions of the category.

Double Suicide at Nishijin (1977) by Yoichi Takabayashi

As mentioned before, one of the most impressive aspects of Yoichi Takabayashi‘s work is the fact that the story, despite taking place in the 70s, could easily be a period one, in an approach that probably aims to show how, despite technological progress, some things, and particularly the place of women and the poor in the society, remain the same. The textile business, the relationship of the two, even the dresses Yumi wears, sometimes kimonos, sometimes western/modern ones all point towards the same direction, in a truly impressive feat.

The Love and Adventures of Kuroki Taro (1977) by Azuma Morisaki

Azuma Morisaki directs a film with an intensely episodic approach, which is highlighted by both the aforementioned arc and the involvement of a plethora of characters, which also include the owner of a gag toys shop. Evidently, the fact that the two main protagonists, Taro and Juichi are in the movie industry, plays very little role in the movie, which moves into completely different paths than what its intro suggested. As such, it seems that the story (also by Morisaki) is based on a series of people and events that he experienced at some point in his life, as the father arc suggests, although not even that is a certainty. The episodes do not have much connection with each other, and their only common ground is the protagonist and the acerbic humor Morisaki implements throughout the movie, which occasionally borders on being blasphemous.

Eros Eterna (1977) by Koji Wakamatsu

In a style that reminds of de Sade's “120 Days of Sodom”, the movie revolves around a priestess who believes she is the reincarnation of the Happyaku Bikuni-sama, a legendary nun who lived for eight-hundred years but retained the youthful appearance of a young woman throughout her whole life, and her interactions with a number of men of all levels of society, all of which end up in something between rape and sex with consent, while the priestess frequently stating her will for someone to kill her. A secondary plot revolves around a younger shrine maiden and her boyfriend, who constantly pressures her to have sex with him, before he leaves the area to go to a good university and get a good job. The girl repeatedly turns down his advances, despite his feelings for him, because she is essentially afraid of sex and men altogether. Eventually, the boy becomes obsessed with the nun, peeping on her sexual endeavors and her taking notice after a point.

Third Base (1978) by Yoichi Higashi

Yoichi Higashi directs a film that is essentially split into two parts, with the aforementioned flashback actually taking a rather big portion of the movie's duration, starting about the middle and finishing close to the finale. The first part presents the particular penitentiary with a style that borders on the documentary, with the procedures that took place for the rehabilitation of the young men being portrayed in detail. In that fashion, it becomes evident that the juvenile institutions in Japan are actually reform schools, with the inmates learning to do various jobs, from welding to working the fields, while the employees were more councilors than jailers, frequently being involved in advisory sessions with the inmates, either in groups or personally.

Double Suicide of Sonezaki (1978) by Yasuzo Masumura

The melodrama derives from the overall story, with the two protagonists being inherently good, but finding constant obstacles in their will to be together, most of which have to do with their lack of money, in an element that connects the film with Masumura usual critique of society, although this aspect is quite toned down here. That despite their good intentions, everything goes from bad to worse for them, with very few moments of relief, also moves into the same direction, as much as the titular ending. It is this element that also connects the story with the violence aspect, with the punishment the two face being quite brutal, and even excessive in its lengthiness on occasion, as in the aforementioned scene, with roughly the same happening in the finale, although much more briefly. Brief moments of nudity, mostly of Kaji, add a slightly erotic element in the movie, but the surprise factor comes from ]Masumura managing to include moments that are bound to make his audience laugh, even among all the aforementioned elements, in definitely one of the best aspects of his direction here.

The Strangling (1979) by Kaneto Shindo

However, in the beginning, Yasuzo does not seem to mind particularly this insistence, essentially being a good son in all aspects. Things, though, change for the much worse when the first notions of sex start getting into his mind. The whole arc with his classmate, which starts with a flirt to an attempted rape, to a night in a hotel in the mountains, to a revelation of actual rape, a murder and a suicide, mess the young man's head in ways he cannot handle. An incident with his father, and the fact that the only parenting him and his mother offer is taking care of his basic needs (food, a place to stay etc) and the push towards the aforementioned path, somewhat puts them in the spotlight, but not to a point that can justify the young man's action moving forward. The disgust for his father eventually seems to derive also from an intense Oedipal complex for his mother, with Tsutomu feeling highly antagonistic towards Yasuzo, not to mention having clear sexual notions for his mother.

Tattoo (1982) by Banmei Takahashi

Much like another ATG title, “Aesthetics of a Bullet”, Banmei Takahashi directs a character study about a loser who thinks that he is something more than he actually is, with the only thing essentially making him stand out (and in a negative way) being his proneness to violence and the way he gets obsessed with things. The analysis element, though, does not stop there, as it actually extends to the two main female protagonists, Michiyo and Sadako, both of which are equally interesting characters.

17. The Crazy Family (1984) by Sogo Ishii

Sogo Ishii takes the term dysfunctional family and transforms it into something much worse, as paranoia is the permeating status of each member. In this fashion, however, he mocks the standards of modern Japanese society, in a quite evident metaphor. Katsuhiko represents the middle-class white-collar worker, whose petit bourgeois dreams include having a wife, two kids (one boy one girl) and a house. Saeko represents the modern housewife, who sits at home all day cooking and raising the children, without any other, actual interests. Masaki's character mocks the fact that teenagers are obsessed with attending a good university, to the point that they think their life has ended if they fail. Erika is the archetype of the girl that wants to become an idol, as her self-absorbedness does not let her care for anyone or anything else. Lastly, Yasukuni represents the previous generation that still clings on the imperialistic grandeur of the past. In the meantime, though, its members have become a bother for their children. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

The Deserted City (1984) by Nobuhiko Obayashi

The microcosm of the ruined future of the city lies in the ailment of the Kaibara family. In the beginning, the syndrome is not evident, but soon it manifests itself through the absence of Naoyuki and Ikuyo. Yasuko herself is a living, breathing microcosm of the town and its destiny. The continually cheerful teenager once notes to Iguchi that her sister has the same sad smile as her mother. Nevertheless, she is the most melancholic character of a movie composed solely out of them. She is a member of the youth who does not leave the town in the hope of a better, bustling life. Even a fraction of youth continuing to stay in the town is apparently a symbol of enormous hope for its future. However, what they, and the community, need to survive is protection and assistance from the older members of the society. Society fails to support Yasuko when she needs their assistance. As her personal life breaks down in front of the townspeople, so does the fortune of the community to survive the waves of destiny. (Raktim Nandi)

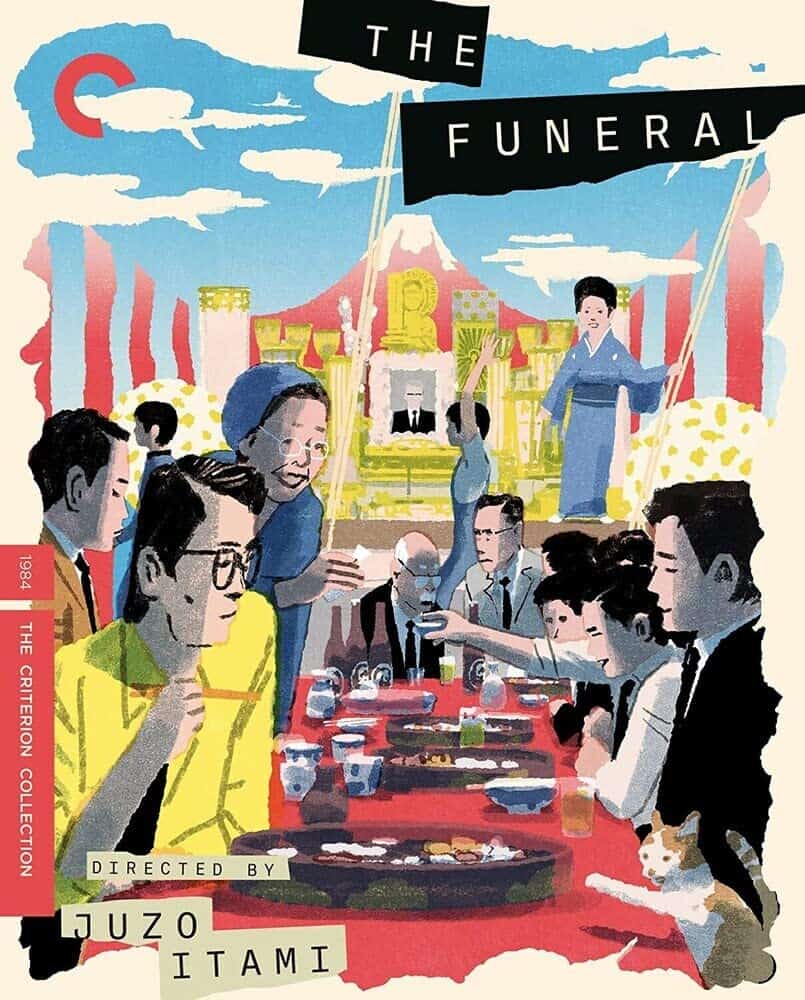

The Funeral (1984) by Juzo Itami

Using his trademark episodic, filled with characters approach, Juzo Itami comes up with a movie that seems to focus on the gap between two generations of Japanese people, and particularly how the obsession with tradition and etiquette of the previous one was simply a burden for the new one. Furthermore, the fact that the latter still had to adhere to every detail, makes a comment about how heavily tradition, and also the “what will people say” concept weighed for everyone in society, with this aspect being the main source of comedy here.