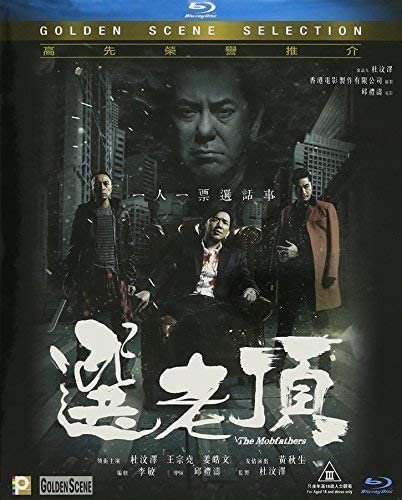

Herman Yau tackles political and social issues, re-proposing the classic atmospheres and themes of Hong Kong Triade cinema in “The Mobfathers,” a gritty and satirical tale of power struggle and a nod to Hong Kong's troubles with the China-manoeuvred elections.

Buy This Title

on Amazon

The film begins immediately in full swing, with a violent brawl in which Chat (Chapman To), the head of the Metal gang, is arrested and locked up in Stanley prison, just as his beautiful wife discovers she is expecting a baby; an event that for wrong timing fails to divert the course of fate. In fact Chat, with a 5-year sentence, is going to miss the birth and early years of his son and has no other options than to leave his trusty lieutenant Luke (Philip Keung) in charge of the boys of the gang, and also to take care of his wife and child.

In prison, Chat, fluent in rhetoric, practices his leadership in a microcosm that has nothing to envy to the ‘outside' in terms of violence and strict hierarchies. When the longed-for day of release arrives though, things do not unfold as expected, as another episode of violence almost causes him to be arrested again. His wife, fed up with his long absence and his incorrigible conduct, does not seem in the mood to celebrate his release, and that same evening Chat seeks distraction in a night club where a lap dancer, in a rather comical moment of the film, reads his future in the cards; a future as the sole head of all the gangs of Hong Kong. From that night on, Chat decides that his old position as leader of the Metal gang is no longer enough, but he wants to become Dragon Head, holder of the supreme power. This role now belongs to Godfather (Anthony Wong), who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer and therefore is destined to vacate the post very soon. Following the tradition of the Triads, the Godfather and the elders of the “family” appoint Chat and another gang leader, Wulf (Gregory Wong) as contenders for the chair, and prepare to vote for them in their inner circle. Chat, however, wants the suffrage to be universal and rebels against the old system with bloody consequences.

The intricate political situation of the former British colony of Hong Kong has been worsening in the years following the handover to China, to the point of escalating into fierce protests in 2014 by the so-called Umbrella Movement, whose echo in the recent years has strongly resonated in the West too. Consequently, this situation reflected on film production which has always had a very strong popular base in Hong Kong, and influenced the success of the films that have stood out those years. To name one, “Ten Years” (2015), Hong Kong's collection of dystopian visions of the near future that was awarded Best Film at the Hong Kong Film Awards. Herman Yau is a director who likes to interweave social themes into the plots of his films, against backgrounds that often wink at more pulp genres, sometimes with chaotic results, such as in “Sara” a film that seems to suffer from a split personality. Also in “The Mobfathers”, Yau and his regular screenwriter Erica Li introduce a subtext, in the second half, that gives a nod to the controversy about China's control over the elections for the Hong Kong head of local government, with Beijing government imposing the candidates to vote, invalidating the concept of universal suffrage with unmanned candidacies. This premise is necessary to understand better, not so much the film – which can stand in its own right – but at least the very specific militant intentions of the director.

Formally, “The Mobfathers” bluntly harks back to the films of the great gangster/Triad genre tradition of Hong Kong cinematography, such as Johnnie To's “Election” or even the “Young and Dangerous” series. Herman Yau's skilled storytelling and his gritty setup does not disappoint overall, if not for some inexplicably sloppy details. The film is extremely curated in the visual aspect: the photography is saturated and elegant, the nightclub interiors and the streets exteriors are captivating, the gang brawls with machetes have style and are well choreographed, there is even a notably sexy nightclub show (the film is Category III). However, sometimes it stumbles over some low-budget special effects that badly match the rest, like some very unconvincing CGI blood that risk making some fight scenes less powerful than they could be.

Chapman To, who is also the film's producer, gets his teeth into the role, impersonating the gangster in a rather histrionic way, but somehow, he remains slightly unconvincing as Chat. Perhaps the memory of all his previous comedy / zany roles is difficult to shake off, and the actor's soft and “likable” physique doesn't help this case (although, in the past, Wong Tin-Lam, Eric Tsang and Lam Suet played memorable gangsters even with their corpulent build!). Who truly stands out here is Philip Keung, who confirms himself as one of the best underdogs (unfortunately) of Hong Kong cinema in another of his brilliant supporting roles. Anthony Wong, on an other hand, manages to be the most charismatic figure in the whole film even with just a handful of minutes of stage presence, shaping his character through a cheeky mix of Coppola's Godfather, Bond's nemesis Blofeld, and even a little bit of Darth Vader.

All in all, despite some minor flaws, “The Mobfathers” is a pleasant addition to other Triad films and will not disappoint the fans of the genre. It is a bit the “same old story”, but the director's allegory of the political situation of the moment and the strongly nihilistic tone give it a breath of pop topicality.