Indian editor, writer, director, cinematographer and producer Mahesh Narayanan is attached to the province of Kerala where he was born and raised. After a significant ammount of films he signed as editor, Narayanan made his directorial debut in 2017 with the critically acclaimed drama “Take Off” about the ordeal of Indian nurses in the city of Tikrit, Iraq in 2014. With his latest feature length film in the International competition of Locarno Film Festival, Narayanan is the first Indian director whose work is shown in this prestigious festival since 2005, which was more than a reason enough to meet him in Locarno to discuss his idea for a movie inspired by true events, the environment he chose to set the story in, the position of women in Indian society and his very deep connection to Kerala.

“Declaration” is a film that shows the hardships a married couple working in a latex gloves factory faces after a manipulated skill video appears on the internet, in which the wife allegedly performs a felatio on someone during her shift. Even though the woman's face is covered by the mask, the conclusion of everyone who's seen the video is that it must be her and no one else. Why else would it come with her skill video? This kicks off a series of unpleasant events, klifting the arranged marriage between the two, and diminishing their chances of getting visas to immigrate abroad.

AMP met with Mahesh Narayanan the day after the film's world premiere in Locarno.

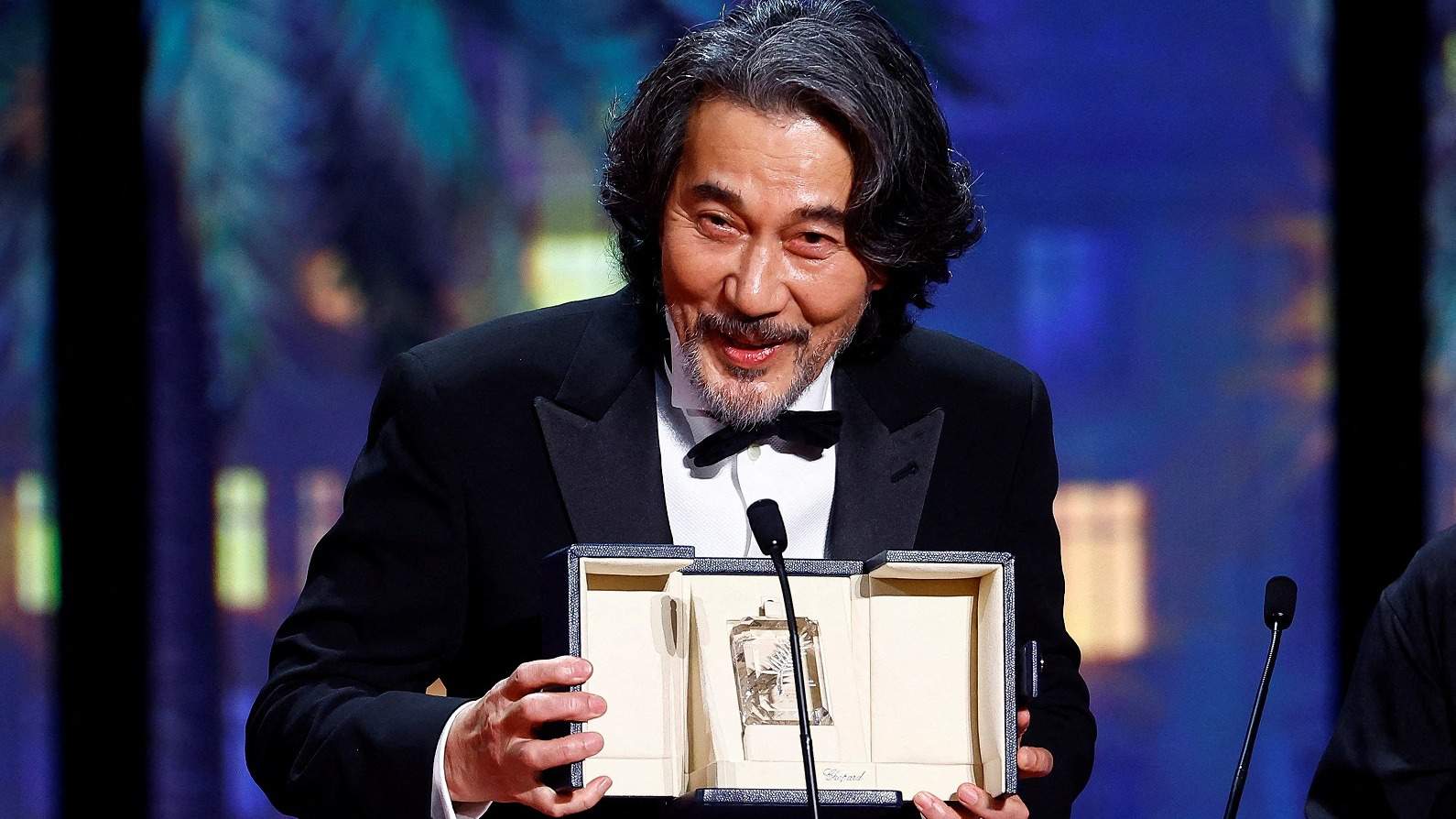

“Declaration” screened in Locarno Film Festival

As the Artistic Director of the Locarno Film Festival Giona Nazzaro underlined while introducing the film to the audience right before its world premiere, Ariyippu (“Declaration”) is only the 4th film in Malayalam language screened in the history of the festival. But you, being the filmmaker from Kerala, you are both attached to the language and the region since the beginning of your career.

I graduated in editing from film school, and then I moved to editing films in Malayalam. Then I started telling my own stories, inspired by true events from my surrounding, especially such related to migrant people. Basically, you see people from the Kerala community literally everywhere. It's a global community because, you know, in terms of nursing or labor, the so called skillled workers, the people who need to travel to make a livin,g find their way to get the jobs.

Most of these people don't want to come back to Kerala. This is probably passed from generation to generation. They build massive houses back at home, but apparently nobody is staying in them. Sometimes their parents would stay there but since nobody wanted to come back and spend time in Kerala, not even their grandchildren, it became kind of pointless. And, I was always interested in the low middle class, or to be more precise in people who are trying to migrate, so most of my stories speak about them.

It's also the first time in 17 years that an Indian film is in the main competition of Locarno Film Festival. What is the feeling like?

I don't know why Indian films were not received that well in Locarno all these years. The last one to be shown was Rituparno Ghosh's “Views of the Inner Chamber”. I am looking into the fact that all these years there wasn't an Indian feature to compete in the program, and I was trying to mix things. The film is neither commercial, nor does it directly belong to arthouse cinema. It took me three films to make an honest effort from my side. It's also the first time that I am realizing the film theatrically, and not on platforms. So, I am quite happy.

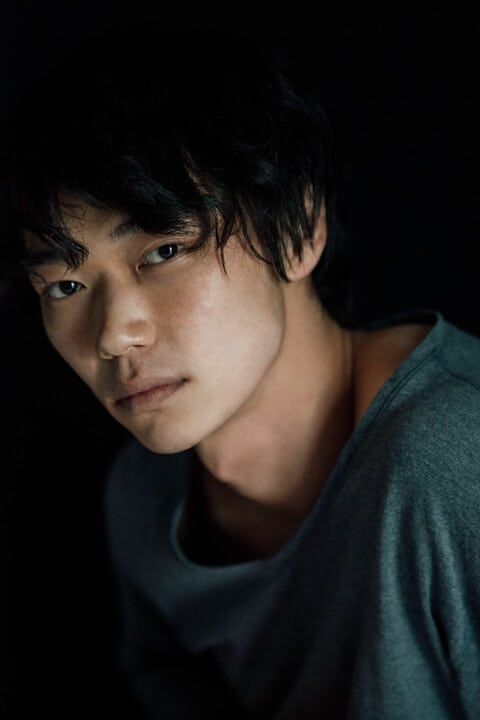

“Declaration” is your second collaboration with Kunchacko Boban who took on the double role of producer and lead actor. Can you describe the form of your cooperation?

There are two actors that I am regularly collaborating with, and Kunchacko Boban is on board only for the second time. What I require of a collaboration is basically to justify the investment, as we are putting our own money into the film. I am not answering to any kind of investors, so we trust each other. All this time, I honestly tried something that I could pitch globally, and it's a great thing to be having the film in Locarno's main competition program. We are actually quite looking forward to be releasing the film in India by the end of the year. But, normally what's been happening in India recently is that the moment you go for an international festival, the film is being treated as non-commercial, and as an arty kind of thing. So, for the distributors and producers, as well for the distribution platforms, it's connected to reservations. If people feel like that they are dealing with an academic film, there are no big chances for it because the whole of India is behind those Bollywood productions. The niche audience is very small, and that is actually the truth. Nowadays, I feel that we should recover the money we invested, and travel a little bit, after which we will release “Declaration” in India. What I am telling you now, is also something that I said to all my collaborators.

Your story is based in Noida, a satellite town to New Delhi, in which lot of tragic things are happening to a couple who is actually in temporary migration before migrating somewhere else. You mentioned in your statement that you were inspired by a true story. Can you elaborate?

It is something that I found in an article in a Bombay newspaper. It was very simple. A bank employee was asking for a declaration from the judge, which was a totally weird kind of thing. She approached the judge, and there was actually no case in that, but the only thing she wanted was justice, and a paper to clear her name. A sex video with her lookalike appeared on some porn sites, and because of that she was getting humiliated in her workspace, but also in personal life. Her husband and children were also accusing her. So she looked up for a judge in Bombay. Even he didn't know what to do at the beginning because there was no similar case before. The thing is, she wanted to have an official proof to show it to her colleagues and family, or anywhere she went. Then, the judge asked her what the purpose of it was, and she replied that she only needed a certification. So, she got it. The question is – what is the use of it? I was thinking hard about it for a long time, because certain stories stay with me for different reasons. So, I started developing characters around that idea.

Also, even before the pandemic I became interested in the medical field labourers, particularly in factories producing medical masks or gloves. There is a huge number of people from Kerala working in the latex industry because of the rubber. This is why I brought the idea of setting the story into this environment. And there was also a need of a video presented to an embassy, a consulate or to certain agencies specialized in recruiting skilled workers. That means that the workers are forced to prove their productivity in a short video, which is a very curious thing, and also particularly mean. So, the story was born out of those elements.

The plot development surrounding the manipulation of the skill video is very entangled, and I was wondering about the layering of that part of the story. What was the idea behind it? It can't only be about introducing a thriller element into the film.

For me, this can be treated as a feminist film, but at the same time I don't want to become someone who shouts a loud propaganda. I think that the Indian society, especially the low layers, and the lower middle class still pretty much believe in patriarchy, that the woman should please her husband and that the bonding within the family is very important, this kind of things. If you look at it, there are three strong women in the movie – besides Reshmi (Divya Prabha), the factory supervisor and then the factory owner who appears at the end of the film. If you observe them closely they are trapped in that setting because all of them are still dependent on their male counterparts. Reshmi's husband is a control freak, the factory owner is there only pro-forma because the place runs under her name, while it is controlled by her husband, and the supervisor is dependent on her immediate, male management. Men can not deal with their situations, and still women are not taking any kind of credit for solving problems. Eventually, none of them wants to get away from the factory, because it's all an instilment of things, even though they are exploited.

The other side of the story is that there is also a matter of convenience in case of Rashmi and Hareesh. It's not a love marriage, but a very traditionally set up, arranged one. There is a line in the film when she tells the supervisor: “First I came, then he did.” That's a normal thing. One skilled worker gets employed first, which usually is a woman, and she would be either a nurse, a maid or similar. She would, as first, get a chance to be employed, and then she would sponsor her husband. I know a lot of stories where nurses would go first, and then their husbands would become drivers or security in the hospitals. So, the ladies are superstars who help their husbands get a job. In that scenario, there is no such thing as a skill video of a man. It's all about women and what they can do. It's about the skills of Hareeshe's wife that her husband will exploit.

I want to get back to the working class environment depiction per se, and my next question relates to all the permits one had to acquire for the purpose of shooting the film. Also, was the film actualy shot in Noida?

We visited 30-35 factories in the country to find the right place just for the sake of people who work in them. The situations depicted in the film have actually really happened in India. The dirty gloves scandal is real. Since it was like that, we wanted to shoot in a factory. You see, what actually happened was none of those factories stopped their production during the pandemic. They were continuously running, and because they were all companies making a huge profit out of the situation, earning hundreds of millions of dollars, none of them were ready to give us space to shoot the film. We had to build the set, and the funny thing is that there was a unit line in the country which was not in use because it was faulty. My production designer built the whole factory setting. Everything you see was the fantastic job of my production designer. We also hired a group of workers from a nearby village who worked in such factories, and knew how those things were done. So, basically, only Divya had to train how to test those gloves, which took about two weeks of training. Otherwise the others would have felt odd. She had to somehow fit in. I didn't want to give those people the feeling of not belonging there.

How long did it take you to shoot the film?

The film was shot during the second wave of Covid-19 pandemic in India, in Delhi. The problem was that since our film was independent, we didn't have much of the equipment, but we had a lot of actors inside of the factory. We had, for example, 80-90+ people working all the time, so we had to interrupt shooting from time to time due to Covid. All in all, the shooting took some 35 days. Since it was very hard for us to shoot under such conditions, we had to please the government officials by saying that we can use the story in the film. I was always of the opinion that one should seize for the moment, because if not – certain stories will expire. So, one can change the scenario. I am really convinced that there is an expiry date for certain ideas, and that things have to be told at the moment they are happening. Almost all people in the film are wearing masks, they are in the pandemic, they live and work during the pandemic.

Your film was originally inspired by two stories that you put together, but then you also built in a political element by showing the conservative side of the province, and how unwelcome ‘foreign' workers are. I would like to address this migration aspect. I guess that people who don't know much about the specific relations in India, won't understand the position of workers coming from Kerala.

I will give you an example by saying something about my debut feature “Take Off”, which was about nurses going to Iraq. If you look at it in detail, it is not just drama, it has other layers as well. Some think that it's a survival drama because people got stuck in Iraq when ISIS took over. When you watch the film, there is a sequence in which I show those people going to Iraq. They didn't even know about the current political situation of the country they were going to. They believed Iraq to be something like the UK, or Germany, or even the USA, because any foreign country is better than India. There is a notion like that. Some of them, when they actually landed in Iraq, found out that there was a civil war with two parties fighting, and since they landed a job in the military hospital, they were not allowed to leave the premises. Some of them have never seen anything outside of the hospital, because they were accommodated in shelters, and everything was inside. After a few months, they realized that they were not paid because the war was full on, and the sad part is that when ISIS took over the hospital, some of those nurses offered to work for them. Even though they are trained nurses, there is no awareness among them. So, literally no one enlightened them, no one told them about where they were going to, and under what conditions they were going to work.

Check out the review of the film

These things happen because people in India are so underpaid that they don't ask question when the opportunity to go abroad presents itself. Nurses and skill factory workers are very underpaid, all those people you see in “Declaration” and that we took from their real factory milieu, most of them are college or even university graduates. Some of them hold master degrees, but there are no jobs for them. They need to financially help their families. So, what to do? The major thing is to get away. Most of the young people in training have one aspiration only – to fly. Flying means being abroad, having a better life. For instance, women in the second year of nursing school already start attending German or French courses. So, it's not about nursing at all, it's about leaving the country.

Back to the film, your drama shows how deeply the patriarchy steers the Indian society. The husband Hareesh (Kunchacko Boban) has a toxic, suffocating personality, and a huge sense of self-entitlement.

It's not all that black and white, it's more of grey all over. He is dark and agressive. He simply has to control everything, and gradually he gets poisoned by his doubts. There is also this other side. When he understands that the girl on the video is not his wife, he can't even look her in the eyes. There is the scene when this happens. He sits with his head bowed down, and she is looking at him silently. But, he is kind of quick to ‘forgive', which is funny, and says things like “everything is ok now.” Nothing is ok, of course. But you see, if something happens from the perspective of a male, Indian audience feels that it's common, and ‘natural.' An Indian man thinks he gives his wife enough freedom because he lets her work. And that is not freedom, that is work. This is what I was talking about. It's all about the convenience.

The title of the film can also be read as Reshmi's declaration of independence from her husband.

Yes, she even cuts her ring, because she needed it to make a clear cut.