by Nguyễn Minh Tiến

How can one cinematic production ever be called “a documentary”? In recent years, this debate on a concrete definition of “documentary”, which is merely impossible to reach, has constantly helped filmmakers as well as the audience, especially film awards jurors (since they are also a type of audience), redefine their points of view on how “actual realities” were presented in those documentary films (Aufderheide 2 and Minh-Ha 89). Even when given the same topic, filmmakers could still create various types of documentaries based on their artistic approaches to the “reality resources” (Minh-Ha 85) stored not only in archival centers but also in their daily lives.

Nevertheless, it would not be fully applicable to Vietnamese documentaries. Even though the Vietnamese film industry produced more documentaries than feature films (Thi DocNet Southeast Asia) there has not been a significant increase in international acknowledgement and recognition. Hence, one major aspect that influences this underdevelopment of Vietnamese documentaries is the overuse and misuse of voiceover. By analyzing examples of documentaries made by Vietnamese directors and about Vietnam's society and culture (with the addition of some international titles to enhance the argumentative thesis) throughout this paper, I demonstrate the argument that exploitatively using voiceovers in Vietnamese documentaries, on the one hand, creates nostalgic reminiscences of a distant past while pushing the polarization procedure to a greater extent on the other hand.

As old as the voiceover

Undoubtably, voiceover techniques have been used since some of the first talkies (a sound film with dialogues) dated back to the 1920s, roughly 30 years after the first documentary shorts made by the Lumiere brothers premiered (Pillai 1). It was then used mostly for propaganda purposes (Aufderheide 11) during the height of the Second World War. The Nazis used documentaries to portray their powerful army as something other countries should be afraid of. Therefore, when watching a documentary film, audiences can easily draw upon the nostalgic reminiscences of dogmatic or state-sponsored forms of storytelling (Aufderheide 18) with specific agendas imposed within those visual contents. Thus, voiceover was one of the most directed (Nicholson 221) and celebratory forms of narration in documentary filmmaking in the early 20th century, in which directors could guide those images collected on battlefields and “speak” whatever they wanted during the editing process (Bernard 211, Nicholson 222 & 223).

Đặng Nhật Minh's Tháng Năm – Những gương mặt (1975) captured some of the first moments of Saigon after April 30th, when North Vietnam's Communist government took over the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) in the South, reuniting the two regions and modifying political and social orders for the new era without any foreign interventions in this territory. The voiceover, mostly in the third person, heavily criticizes the failure and devastation caused by the American army and its puppet Vietnamese governors on the city, while extolling the victory of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and their alliance, the National Liberation Front, over those enemies. It concluded by assuring that the new government would look after the RVN soldiers, giving them opportunities to revive their lives once their reeducation period was over. Tháng Năm – Những gương mặt or other documentaries that focused on historical events or were filmed on such battlefields, on the other hand, enforced reasonable senses of reflexivity, whereas for many of the directors, it was not plausible for immediate editing and sound engineering, hence the involvement of “invisible hands of Gods” that give the omniscient viewpoints should then be applied for contextual and pedagogical purposes.

Using voiceovers in documentaries, while being a traditional method of incorporating informative sounds into a film, carries uneasy-to-digest and problematic instances of hierarchy and manipulation, nevertheless. Just before when the Đổi Mới policies (perestroika) took place in 1986, Trần Văn Thuỷ had presented his critiques in two documentaries Hà Nội trong mắt ai (1985) and Chuyện tử tế (1982) on so-called “sensitive topics”. These were rumored to have been considerably censored before having premiere to mass audience's films while still dominantly led by a male voiceover, it had let some participants to talk on screen and discussed what they were thinking on the given topic. This demonstrated that voiceover had long been on the highest peak of the most powerful form of narration (Nicholson 223). Furthermore, when examining voice-over hierarchal positions in relation to gender and race, it is easy to conclude that the majority of voiceovers were performed by white males (Pillai 2), giving power to an absolute minority. For instance, in the three movies by Trần Văn Thuỷ and Đặng Nhật Minh, the male voiceovers appeared to have knowledge of almost everything that occurred on those days. They represented the directors' actual evidence of having witnessed what had happened, showing that, at least in the broadest sense, they were witnesses as well as experts and it was legitimate to talk about those topics (Chovanec 11 & 12), even though the narrator had not likely had the shared experience and could absolutely be invited to the film's post-production only (Bernard 217). However, this pseudo-expertise that may have sounded persuasive to many people who did not share those vivid memories may have proposed a different kind of threat, information manipulation. For many RVN soldiers and their families, the effortless adaptation to the new government would not necessarily be true, given that the refugee crisis occurred almost immediately after the fall of Saigon and lasted until the last decade of the twentieth century. Trần Văn Thuỷ's Chuyện tử tế rather significantly reduced the tensions between the ordinary people and their distrusted government, hence framing realities in a much more distorted way, the director's way of interpreting those stories (Rascaroli 8). Had the voiceovers been done inefficiently, it would have created the dilemma of false realities (Nicholson 229), particularly when fact-checking in nowadays' society tends to be seen as a survival skill.

Simply younger and more individualized

The shift from state-owned dogmatic documentaries to various independent filmmakers reaching out to world-renowned film festivals has slowly progressed as Vietnam has long changed its economic management from a subsidized economy to a socialist-oriented market economy, giving individuals the power to produce films while the state maintains its long-established institutions (with minor moderations to state-owned film corporations such as Công ty TNHH MTV Hãng phim Tài liệu và Khoa học Trung ương, Hàng Phim truyền hình Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (TFS) or Công ty TNHH MTV Phim Giải phóng) , for (again) propaganda purposes (Thi, DocNet Southeast Asia). Subsequently, it polarizes how independent filmmakers tend to experiment with different kinds of narration while state-owned institutional directors strictly follow the old method, doing monotonous voiceover.

This can also refer to the absence of voiceovers in documentaries, giving more room for the actors to have their own voices heard. Hence, to achieve this mode of filmic technique, the director's position or the existence of the camera should not be present throughout the film. Phạm Thu Hằng's Mùa Cát Vọng (A Future Cries Benath Our Soils) (2018) gives the audience a glimpse into the daily lives of four men living in post-war Vietnam. The film cuts off the director's interventions by only providing spaces for the protagonists to interact with each other throughout the film. No commentary voiceovers from the director were made, giving the sense of the disappearance of “the invisible hands of God”, and letting the audience truly experience someone's daily life. This movie is an example of what reality in documentaries should have looked like in realism theoretical frameworks since they present nothing other than what actually happened, with the least interference from the director on the editing table. This mode not only provides the fundamental technique in documentary filmmaking, giving both the director and the audience “observational-sensory” access to feel as close as possible to how the actors in the documentary felt while participating in those projects, it is also one way to differentiate Vietnamese independent documentaries from state-owned ones (Chio 33). The following two examples may not fully diminish the directors' physical participation with the protagonists, Chuyện thầy Đức (Love Man Love Woman) (2007) by Nguyễn Trinh Thi and Bolinao 52 (2008) by Duc Nguyen, both, however, seem to have created dialogic conversations when the protagonists keep on telling their stories by answering the director's unvoiced questions, interacting with the camera that represents the directors' perspectives, but at the same time, respecting an individual's perspectives and letting them tell the story in the way they want to (Nicholls 139). On ethical and legal stances, it projects fewer threats as the directors must respect and minimize their distortions of someone's voice, hence preventing misunderstandings and misinterpretations in the final products (Nicholson 231). Consequently, hierarchal powers were deconstructed through individualization, giving more democratic voices to those who wished to express themselves in various artistic practices.

When the voiceover had been downgraded from its position in documentary films, the challenge as well as opportunity for filmmakers would then be reaching the balance between artistic treatments of both visual and audio materials, hence reestablishing documentary as an art form and not just simply another bland way to illustrate realities (Aufderheide 14 and Minh-Ha 85). Huỳnh Công Nhớ's Cái chân gãy của bà tôi (Grandma's Broken Leg) (2021) parallel editing brought indirect and overheard sounds into their own conversations and visually presented them in the short film. Even though most sounds were digenetic, taken from the director's grandmother's voice, archival clips of a pastor, and a late comedian, there seemed to be no dominance but rather a balance between the visual and the audio, thus making the audience's emotions subjectively change from hysterical laughter to thought critique on how manipulative and misleading religion could be for its followers. Việt Vũ also investigates the impact of still photographs and moving images on the audience's anticipation of the theme of mother of oneself and mother nature in a Vietnamese context. Mùa xuân vĩnh cửu (The Eternal Springtime) (2021) took a poetic approach, as the voices heard in this award-winning short film are the director's citing his proses, calling attention to his mother, as well as the viewer. The movie still presents actual realities but more in a performative way, which marks the director's position both in front and behind a camera (Nichols 150). His audio and visual involvement, thus, dismantles the ultimate omniscient viewpoint that voiceovers tend to create while also signaling to the audience an alternative way to consider the truthfulness of realities and how documentaries can still be an art form alternating non-fictional materials. On a macro standpoint, both Huỳnh Công Nhớ's and Việt Vũ's films, ultimately, provide the freedom of choice independent filmmaking could bring out, allowing more interpretations, more experimentations, and more diverse treatments that are based on personal needs rather than formulaically structured scripts and obsolete topics given by the authorities.

Being innovative means cutting off voiceover…or not

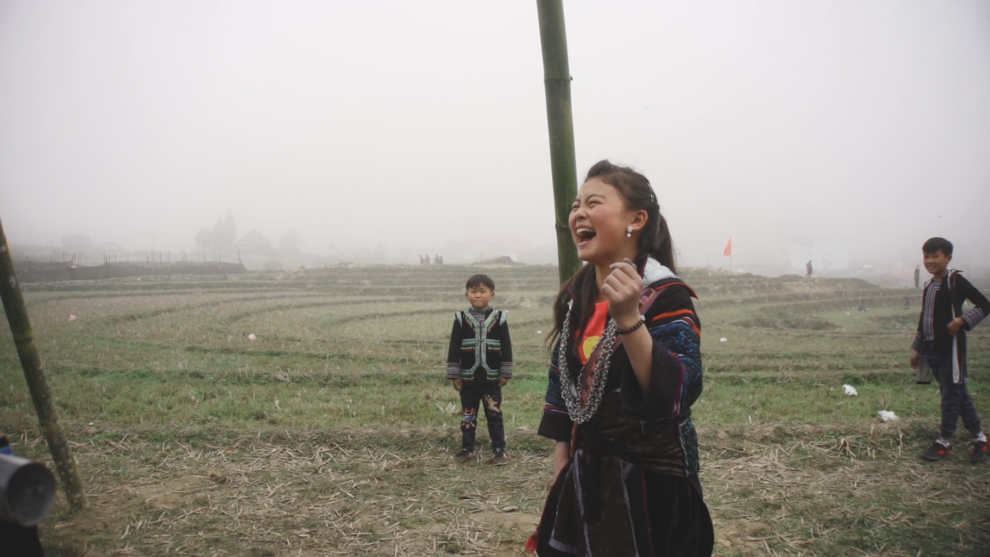

Yet, to avoid taking sides and keep the discussion as objective and well-thought as possible, a question was raised about whether there was any intersectional alternative for voiceover to impactfully engage audiences in documentary films without being criticized as a show-off braggart. In a nutshell, yes. For a longer elaboration, it should be the aforementioned balance in the film, specifically here is the direct, in-direct and overheard sounds for the merging multi-faceted modes of documentary filmmaking. Lê Lâm's Công Binh – Đêm dài Đông Dương (Công Binh, la longue nuit Indochinoise) (2013) and Matt Dworzańczyk's Chợ tình (Love Market) both find interesting ways to attract the audience's attention by aligning different forms of narration and depictions into one single production of each director. From the interviews with the công binh, to reenactments of the công binh's lives while they were deported to France, a female voiceover while reading some of the books on colonialism, and her spontaneous meet-up with a công binh's son on a taxi, to having archival photos and documents presented with a water puppet play, all were narratives Lâm Lê put out for the audience to comprehend who was the công binh. Matt Dworzańczyk took a similar approach by having interviews with the Hmong, having an animated shadow puppet play about his discovery of the invented traditional love market, and having his own commentary voiceover reflecting his journey. Having various treatments for the topics thus refers to the skill improvement, creating more complex stories that can still tell captivating stories, and showing the director's commitment and masterful skills in filmmaking.

Another way to demolish the hierarchical technique of voiceovers is to present them in first-person, which was already limited to the filmmakers' points of view at its core. In Những đứa trẻ trong sương (Children of the Mist) (2021), Diễm Lệ Hà introduces the audience to Di, a 13-year-old Hmong ethnic living in the mountainous region of North Vietnam. Diễm Lệ Hà's did not let her voiceover control Di's life, so Ha's voiceover only took up a tiny segment at the beginning of the film, and the director's own voice only reappears when she interacts with Di and her family members, allowing Di to tell the stories by herself with Ha's camera capture. Những lá thư gửi Panduranga (Letters to Panduranga) (2015) by Nguyễn Trinh Thi is another way to imply the first-person perspective in the voiceover and still leave some room for the audience to fill in their interpretations of the film. The movie is presented as two friends who are exploring different lands in Vietnam, exchanging their findings and thoughts through the form of written letters. These serve as the single narrative approach for the whole film. The literate content matches the visual content in which the filmmakers' concerns about the disappearance of an ethnic group in Central Vietnam as well as the identities of the mine defusers are demonstrated accordingly back and forth. If the filmmaker's script was to follow the participatory mode with the protagonist, then giving the camera to the participant themselves and having them film exclusively personal moments like what the directors of Đi tìm Phong (Finding Phong) (2015) had done, it would then be another interesting way to blur out the fine line between voiceover, indirect, and overheard voices in a film. This practice may help to blur the line between the director and the participant, allowing them all to contribute equally to the final filmic product while also interweaving diegetic and non-diegetic voices into such complexity that the film becomes more engaging to the audience (Hołobut 250). Ultimately, by expanding the democratic artistic practices in documentary filmmaking, Vietnamese filmmakers could then have more confidence to engage in the world dialogues around the world through quality improvements and their wisely treated topics.

Conclusion

By all means, recalling history is acknowledging how we, citizens of a nation, have come through the highs and lows of each nation and each ethnicity's pasts. Voiceovers in Vietnamese documentaries gave a sense for contemporary audiences like myself to reflect on how the regional film industry had come a long way to now reach out to the world with acclaimed rising stars such as: Trương Minh Quý, Việt Vũ, Diễm Lệ Hà alongside with household name veterans: Trịnh Thị Minh Hà, Nguyễn Trinh Thi or Trần Văn Thuỷ. At the same time, it created an invisible wall differentiating Vietnamese independent filmmakers from institutionalized directors in their union with “cultural frontier cadres.”.

It is demoralizing that I once heard my professor, who had his film featured in one of the most prestigious film festivals in the world, persisted on the fact that no one in the world had heard of a “Vietnamese film” with authentic Vietnamese identities, while, at the same time, in his homeland, the agenda to have our revolutionary pasts glorified with unforgettable films that can easily be listed out by examples of wartime documentaries. Had there not been more interventions in state-owned film productions as well as institutions' grant funding plans for independent filmmakers, the “no-name” tag for the Vietnamese film industry in comparison with the rest of the world would still be lingering around and put more pressure on anyone daring to step out of the geopolitical boundaries called Vietnam.

Works Cited:

Aufderheide, Patricia. Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction.

Oxford University Press, 2007.

Bernard, Sheila Curran. Documentary Storytelling: Making Stronger and More Dramatic Nonfiction Films. 2nd ed., Focal Press, 2007.

Chio, Jenny. “Theorizing In/Of Ethnographic Film”. The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video, edited by Phillip Vannini, Routledge, pp. 30-39.

Chovanec, Jan. “'It's quite simple, really': Shrifting of Expertise in TV Documentaries”. Discourse, Context and Media, vol. 13, Part A, 2016, pp. 11-19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2016.03.004. Accessed 20 Apr. 2022.

Trinh, T. Minh-Ha. “Documentary Is/Not a Name”. October, vol 52, Spring, 1990, pp. 76-98.

Hołobut, Agata. “Voiceover as Spoken Discourse”. Audiovisual Translation in a Global Context, edited by Rocío Baños Piñero and Jorge Díaz Cintas, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015,

pp. 225-252.

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. 3rd ed., Indiana University Press, 2017.

Nicholson, James. “Vocal Hierarchy in Documentary”. Vocal Projections: Voices in Documentary, edited by Bella Honess Roe and Maria Pramaggiore, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019,

pp. 219-233.

Pillai, Swarnavel Eswaran. “The Texture of Interiority: Voiceover and Visuals”. Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: An International Journal, vol. 2, no. 1, 2015, https://journalonarts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SVACij-Vol2_No1_2015-Pillai- Texture-Voiceover-and-Visuals.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr. 2022.

Rascaroli, Laura. “Sonic Interstices: Essayistic Voiceover and Spectatorial Space in Robert Cambrinus's Commentary (2009)”. Media Fields Journal, No. 3, 2011. http://mediafieldsjournal.org/sonic-interstices/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

Nguyen, Trinh Thi. “Vietnam Documentary Film: History and Current Scene”. DocNet Southeast Asia, https://www.goethe.de/ins/id/lp/prj/dns/dfm/vie/enindex.htm. Accessed 30 Apr. 2022.

Videography:

A Future Cries Beneath Our Soils (Mùa Cát Vọng). Directed by Phạm Thu Hằng, Cinema is Incomplete Production, 2018.

Bolinao 52. Directed by Duc Nguyen, KTEH/PSB, Right Here In My Pocket, 2008.

Chuyện tử tế. Directed by Trần Văn Thuỷ, Xí nghiệp phim Tài liệu & Khoa học Trung ương, 1985.

Công Binh, la longue nuit Indochinoise (Công Binh, Đêm dài Đông Dương). Directed by Lê Lâm, ADR Production, 2013.

Finding Phong (Đi tìm Phong). Directed by Swann Dubus and Trần Phương Thảo, Atliers Varan, Discovery Communications and Varan Film, 2015.

Grandma's Broken Leg (Cái chân gãy của bà tôi). Directed by Huỳnh Công Nhớ. 2021.

Hà Nội trong mắt ai, Directed by Trần Văn Thuỷ, Xí nghiệp phim Tài liệu & Khoa học Trung ương, 1982.

Letters to Panduranga (Những lá thư gửi Panduranga). Directed by Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Jeu de Paume, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques, CAPC musée d'art contemporian de Bordeaux, 2015.

Love Man Love Woman (Chuyện thầy Đức). Directed by Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Nguyễn Trinh Thi and Jamie Maxtone-Graham (producers), 2007.

Love Market (Chợ tình). Directed by Matt Dworzańczyk, Etherium Sky Films, 2016.

Tháng Năm – Những gương mặt. Directed by Đặng Nhật Minh, Vietnam Feature Film Studio (Xưởng Phim truyện Việt Nam), 1975.

The Eternal Springtime (Mùa xuân vĩnh cửu). Directed by Việt Vũ, Linh Duong and Việt Vũ (producers), 2021.