“Everything changed after St Joseph came” is a line you can perhaps expect from a priest, but not from an owner of one of the quirkiest manufactures in the Philippines. Unless you are talking to the boss of TML Holy Crafts, a company devoted to the production of statues and Christian memorabilia. Thanks to Pope Francis' public comments and admiration, various representations of St Joseph (3$ apiece) were the craze of the recent years, and workers at TML were swamped with high-volume orders of the saint's figurines. In “Divine Factory”, Joseph Mangat, a Filipino American director, takes a look behind the inner workings of the business, and witnesses how the sacred mixes with the profane behind the walls of the eponymous factory. Although the starting premise feels quite confrontational, the end product is an observational documentary which decides not to go for the easiest of blows. It still lacks, however, a clear direction…

Screened in the International Competition section at DOK Leipzig, “Divine Factory” is an awkward hybrid where a typically observational mode is interlaced with scenes in which the characters are directly engaged by the interviewer behind the camera. The ‘observational interview' mixture is counterproductive, as the inclusion of questions and a more dialogic form takes the viewer out of the contemplative mode, clearly established by the first minutes of the film.

However, breaking the observational rules and addressing the characters via interviews allows Mangat to fish something more out of them, only to leave the newly unearthed subplots largely unexplored. The most obvious example? Although a large part of TML's employees are members of the LGBTQ+ community, the issue is only touched upon. The clear tensions between their religion and sexual expression are only briefly highlighted, but, like in case of many other issues, such as drugs or domestic politics, the director of “Divine Factory” returns back to observing, rather than investigating further with follow-up questions.

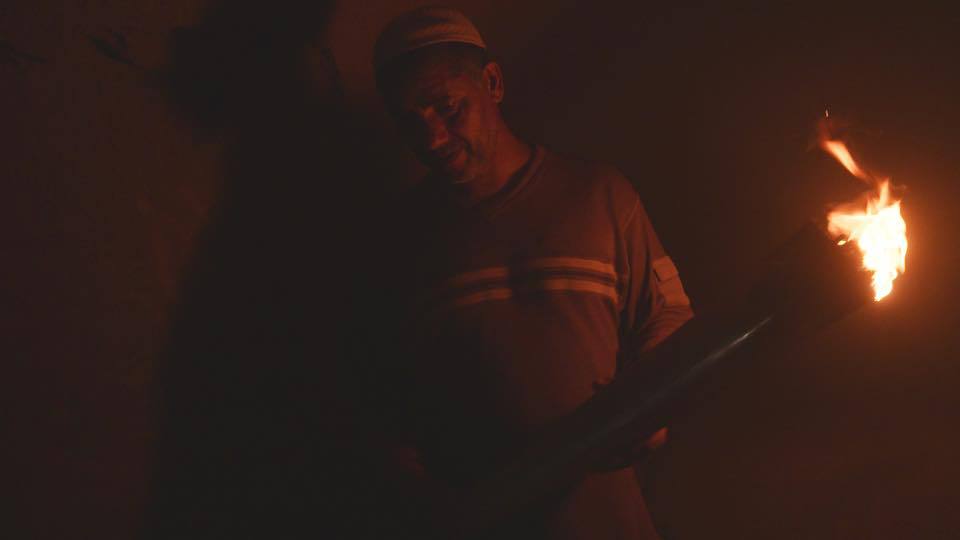

What transpires quite late into the film are its actual objectives. A seemingly simple exploration of the secular-religious tensions, and examination of the commodification of idolatry, sprawls into a deep-dive analysis of the Duterte-era Philippines. This is visible through “Divine Factory's” structure. The wide-angle shots (shot by the Filipino DoP and frequent Khavn collaborator Albert Banzon) often show groups of workers, their heads bent over minute figurines. With cuts between various characters seemingly arbitrary, Mangat asks the viewers to assemble a larger picture out of the pieces he offers. With time, their disparate testimonies begin to fall into place, exposing a precarious world of gig economy. In the “Divine Factory's” microcosm, capitalist mechanisms leave little room for any sort of mistake for the workers. There is also a larger debate within those stories about the various mentality shifts with more money flowing into the country and Philippines evolving because of global capitalism, however the director, rather wisely, decides not to fall into that rabbit hole.

Ultimately, the TML manufacture becomes a pars pro toto for the ails of contemporary Filipinos. As if in a monastery, the workers can carry on fastidiously carving and painting replicas of Saint Joseph, and are able to hide from the violence on the streets for a couple of hours. The brutality of Duterte's regime is both erased and ever-present in the film, constantly lurking and passing in mention, but never openly appearing on screen. “Divine Factory” is at its best when exploring these tensions between what's actually depicted and what's only foreshadowed. This strategy works for most of the cases, to sometimes leave the viewer yearning for more details or context, as in the abovementioned case of the LGBTQ+ subplot.

There are numerous ideas, concepts and arguments within the film. By not fully committing to any of them, the director fails to justify the feature-length of the story. In trying to capture many ideas at once, Mangat does not ultimately elevate what's an anecdotal and quirky story into something loaded with enough content to be deserving a feature-length format. Due to its observational mode, “Divine Factory” assumes an anti-emotional perspective. The kaleidoscopic structure gives an overview of characters and themes, with the director never deciding to commit to any of them. Due to the in-between stance, random segueing between scenes and a lack of cohesion, the film falls short of telling the story in a more engaging fashion.