In the history of Japanese cinema, the period drama, whether a chambara or jidaigeki, is a genre which many filmmakers want to explore for themselves at least once during their career, with many of them even building their bodies of work on just these types of features. While many cite directors such as Akira Kurosawa and Masaki Kobayashi as being the most important examples, cinephiles and people familiar with Japanese culture know the genre is far more varied and has a lot more names to offer. One of those directors has to be Hideo Gosha, who already made a strong impression at the beginning of his career with two lasting masterpieces of the genre, “Three Outlaw Samurai” and “Sword of the Beast”. In the years to come, he would continue making strong entries within the samurai genre, such as his two “Samurai Wolf”-movies, both starring actor Isao Natsuyagi as a ronin named Kiba, nicknamed the “furious Wolf” for reasons which become all too obvious when considering the first feature from 1966.

Samurai Wolf is screening at Metrograph as part of the Hideo Gosha x3 program

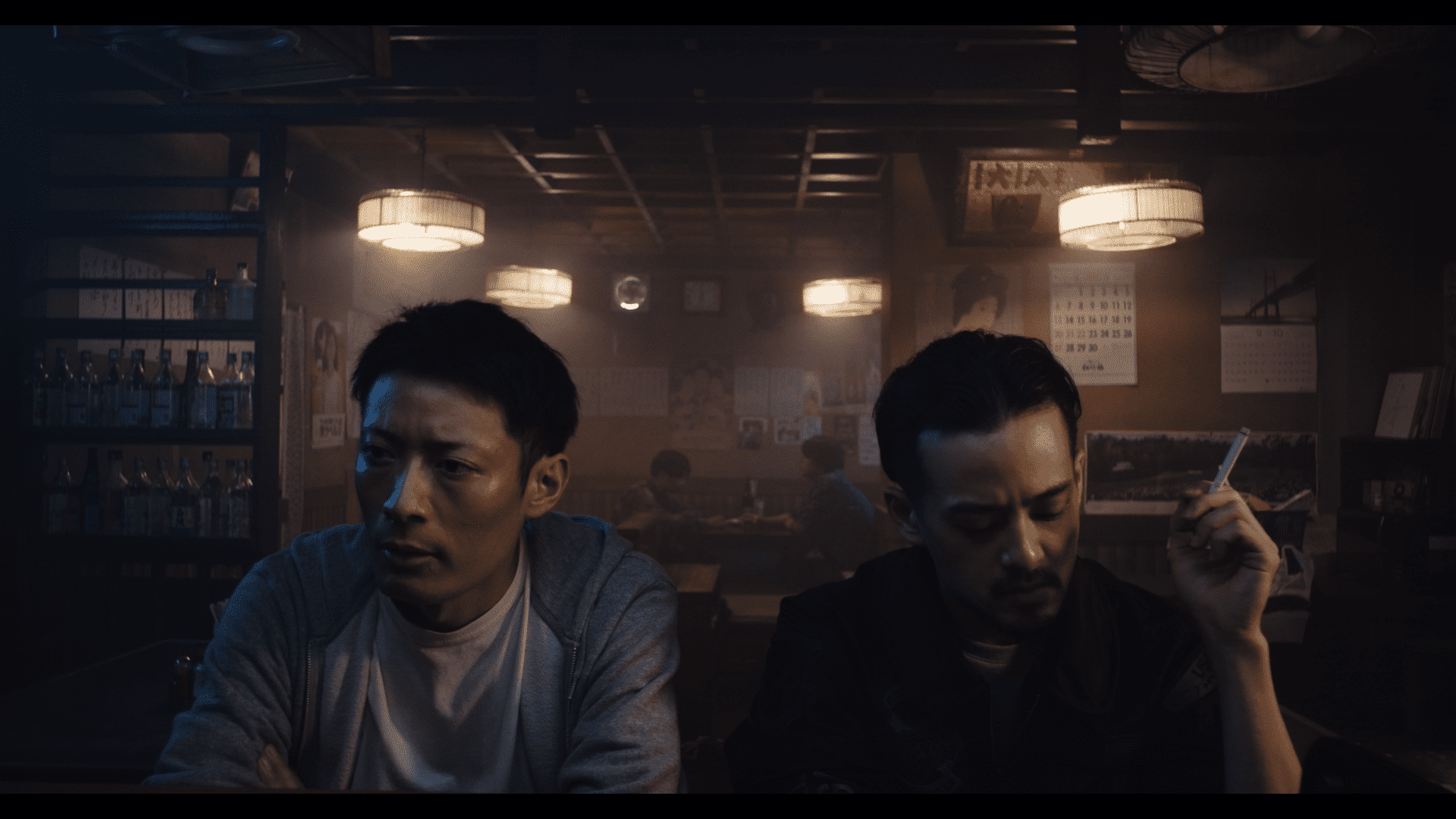

On his way through the Japanese countryside, ronin Kiba was only looking for a quick lunch in a small community, when he stumbles upon a feud between the owner of a relay post named Chise (Junko Miyazono) and a group of bandits, controlled by the power-hungry Nizaemon (Tatsuo Endo), who is protected by the shogun. On multiple occasions, he has sought control over the mail routes in order to gain more power and money, with only Chise and her few remaining men still in his way. Since his actions have turned from blackmail and threats to open violence, the blind woman wants to employ Kiba to help her, especially after she is given the order by the shogun himself to protect an incoming delivery of a large sum of gold coins, which, of course, Nizaemon, wants to get his hands on.

Even though he is hesitant at first, the “Wolf” eventually agrees after Nizaemon has managed to ensure the services of an equally skilled swordsman, the mysterious Akizuki Sanai (Ryohei Uchida). While at the same time fending off assassination attempts on his and Chise's life, a young girl also wants to ensure his services, as she has recognized Sanai as the source of her misery and life and the cause of a massacre in her former home. Matters become even more complicated once the money reaches the village, with Kiba realizing he has become entangled in a personal vendetta and the story of two lost lovers.

There is no denying the influence of Japanese cinema, especially chambara and jidaigeki feature, on, for example, western. However, in the case of “Samurai Wolf” the roles seem to have been reversed, as Gosha's direction, the storytelling and other aspects are strongly influenced by the European western, especially the works of Sergio Leone. While the most obvious example might be Toshiaki Tsushima's score, which is very reminiscent of Ennio Morricone's work on the “Dollar”-trilogy, there is also the overall development from a very simple storytelling concept into something much more emotionally complex. Although monetary interests and power struggles are at the core at the beginning, the plot steadily turns the viewer's attention towards the emotional aspects of the character, shedding light on themes like dependency, trust and guilt.

At the same time, Kei Tasaka's script, based on Gosha's own idea, is defined by strong characters who, similar to the development of the plot, become more complex as the story progresses. While it may be easy to focus on Isao Natsuyagi's performance as the lead character, with moments showing his sense of humor and others his formidable skill as a swordsman, “Samurai Wolf” is much more of an ensemble piece. Junko Miyazono as Chise and Ryohei Uchida as Akizuki have equally memorable moments, with the former giving her character much more depth, which must have been quite the task given the heave melodrama connected to this particular role.

The fighting scenes are also worth mentioning, since, especially in the first half of the feature, rely heavily on slow motion, perhaps in an attempt to showcase the aforementioned skill of the lead character. Later on, they appear to be much more violent and fast, adding to the rising stakes each of these people have in the delivery of the gold and because of their possible personal gain.

In conclusion, “Samurai Wolf” is a great chambara movie, with great performances, direction and interesting characters. Hideo Gosha emphasizes once more in his long career that he certainly knows the genre and how to make it relevant and entertaining for audiences.